Taken from Leonard Swidler, ed., Toward a Universal Theology of Religion (Maryknoll, NY : Orbis Books, 1987), pp. 224 – 230.

Editor’s Note : This is a useful paper unlike any that we have published before, in the sense that it analyzes Kung’s earlier statement on the Prophet Muhammad(P)more objectively and in an unbiased manner (unlike a certain group of Christian missionaries who have expressed disdain on Prof. Kung’s statement!) and gives several reasons for the Christian dilemma in their hesitation to recognise the Prophet Muhammad(P) as being “more than merely a prophet”, as Kung bravely demands. We do not necessarily agree with everything that has been said here, nor will we issue a statement defending what has been said, should the rabid missionaries decide to make an issue out of it.

In Hans Kung’s address to this conference he has once again proven himself a pioneer of inter-religious dialogue. What he has been doing throughout most of his theological career, he was doing again-exploring new territory, raising new questions in the encounter of Christianity with other religions. Although Kung made his greatest contribution in the inner-Christian, ecclesial arena, he has always realized-and increasingly so in more recent years-that Christian theology must be done in view of, and in dialogue with, other religions. As he has said, Christians must show an increasingly “greater broad-mindedness and openness” to other faiths and learn to “reread their own history of theological thought and faith” in view of other traditions. As a long-time reader of Kung’s writings, and as a participant with him in a Buddhist-Christian conference in Hawaii, January 1984, I have witnessed how much his own broad-mindedness and openness to other religions has grown. He has been changed in the dialogue.

Yet I suspect — and this is the point I want to pursue in this response — that in his exploration of other faiths Kung’s pioneer has recently broken into unsuspected territory and stands before new paths. He has been led where he did not intend to go. I think Kung in his dialogue with other religions, now finds himself before a theological Rubicon he has not crossed, one that he perhaps does not feel he can cross. I am not sure. That is what I want to ask him.

In Kung’s previous efforts at a Christian theology of religions, he inveighs against the Christian exclusivism that denies any value to other religions ; he rejects an ecclesiocentrism that confines all contact with the Divine to the church’s backyard. Yet despite this call to greater openness, it seems to some that Kungs on to a subtle, camouflaged narrowness Even though he proposes that we replace ecclesiocentrism with theocentrism, he still adheres to a Christocentrism that insists on Jesus Christ as “normative” (massgebend) — that is, as “ultimately decisive, definitive, archetypal for humanity’s relations with God.“

This is what Kung oposed in On Being a Christian. From recent conversations and from his conference paper, I think that he is now not so sure about these earlier christocentric, inclusivist claims that insist on Jesus as the final norm for all. I suspect that, like many Christians today, he stands before a theological Rubicon. To cross it means to recognize clearly, unambiguously, the possibility that other religions exercise a role in salvation history that is not only valuable and salvific but perhaps equal to that of Christianity ; it is to affirm that there may be other saviors and revealers besides Jesus Christ and equal to Jesus Christ. It is to admit that if other religions must be fulfilled in Christianity, Christianity must, just as well, find fulfillment in them.

From my reading of his paper, I see Kung standing at this Rubicon, at river’s edge, but hesitating to cross. Let me try to explain.

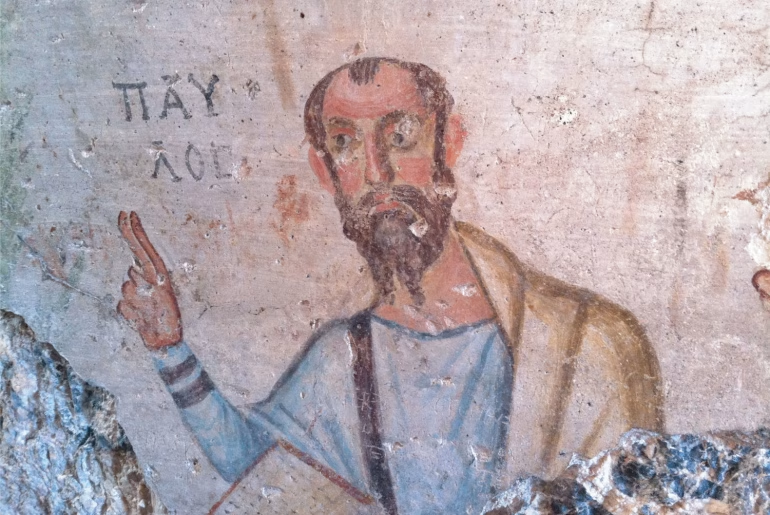

Muhammad, More Than a Prophet ?

In his efforts to urge Christians to recognize Muhammad as an authentic prophet, Kung can only be applauded. Most Christian theologians in dialogue with Muslims hesitate to dare such an admission.

Kung admits that as a prophet Muhammad is “more to those who follow him…than a prophet is to us.” He is a “model”, an archetype, for all Muslims — he through whom God “has spoken to humankind.” Such an understanding of Muhammad, however, is essentially the same as that of the early Jewish christology that was lost and that Kung seeks to retrieve. This early christology, this picture of Jesus — as viewed by his first disciples — which, as much as we can tell, most likely reflects Jesus’ own view of himself — saw Jesus as a prophet, as the eschatological prophet, as he who was so close to God that he could speak for God, represent God, mediate God. But this is basically the same description of Muhammad’s role. Therefore, in its origins, the Christian view of Jesus was essentially the same as the Muslim view of Muhammad : they were both unique revealers, spokespersons for God, prophets.

Kung’s own christology enables Christians to go even further in affirming analogous roles for Muhammad and Jesus. Kung recognizes the truth and validity of the Chalcedon Hellenistic christology, with its stress on two natures, one person, pre-existence. Yet in his own christology as presented in On Being a Christian, in his own efforts to interpret what it means to call Jesus Son of God and savior, Kung relies what is much more of an early Jewish-Christian, rather than a Hellenistic, model.

To proclaim Jesus as divine, as the incarnate Son of God, means, Kung tells us, that for Christians Jesus is God’s “representative”, “the real revelation of the one true God,” God’s “advocate…deputy…delegate…plenipotentiary.“

So I think that Kung might go a further, logical step in what he can say about Muhammad. He points out that if Jesus is understood according to the model of early Jewish Christianity as God’s messenger and revelation, Muslims would be more able to grasp and accept this Jesus. I am suggesting that if Jesus is so understood, then Christians would be more able to accept Muhammad and recognize that in God’s plan of salvation, he carries out a role analogous to that of Jesus. If, following Kung’s keen insights and suggestions, Muslims might be able to recognize Jesus as a genuine prophet. Christians might be able to recognize Muhammad as truly a “son of God”. (And if the title “son of God” is understood, as Kung commends, not so much as God’s “ontological” son but as God’s reliable representative and revelation, perhaps Muslims would be more comfortable in using this title for Muhammad.)

But for Christians, for Prof. Kung to make this move, to recognize the parity of Jesus and Muhammad’s missions, would be to step across a theological Rubicon (as it would be for Muslims as well!). I’m not sure if Kung feels willing or able to make this step. I think I can put my finger on the chief reason for his hesitation.

How Is Jesus Unique ?

The chief stumbling block in Christian dialogue with Islam is not, as Kung suggests, “the person of Jesus and his relationship with God.” In his paper Kung has convinced me that Jesus’ person and relationship with God can be so understood as to allow for the person of Muhammad to share in this same relationship — in Muslim terminology, both are prophets ; in Christian terms, both are sons of God. The problem comes not from the way Kung understands Jesus’ relationship to God, but from the exclusivist adjectives he feels must qualify that relationship : Jesus is not only a prophet but the final, normative prophet ; he is not only son of God but the only, the unsurpassable son of God. (Muslims, with their insistence that Muhammad is the seal of the prophets, reflect this same problem. Here I am addressing my fellow Christians.)

This, I suggest, is the pivotal, the most difficult, question in the Christian-Muslim (as well as the Christian Buddhist/Hindu dialogue): Is Jesus the one and only savior ? (For Muslims : Is Muhammad the final prophet?) Is Jesus God’s final, normative unsurpassable revelation, which must be the norm and fulfillment for all other revelations, religions, and religious figures ?

As I suggested before, Kung in his earlier publications, would answer all these questions with a firm yes. Although all religious figures can be said to be unique, for Kung Jesus’ uniqueness is in a different category ; Jesus is God’s normative, ultimate criterion for judging the validity and value of all other revelations. Kung expressly warns against placing Jesus among the “archetypal persons” that Karl Jaspers has identified throughout history ; Jesus is ultimately archetypal.

If one presses Kung’s most Christian theologians for the central, the foundational, reason why they maintain this absolute, normative uniqueness for Jesus, I think the only real reason they can give is an appeal, perhaps indirect and uncritical, to the authority of tradition or the Bible. This is what scripture affirms of Jesus ; this is what tradition has always taught-there is “no other name” by which persons can be saved (Acts 4:12). There is “one Mediator between God and humanity, the man Christ Jesus” (1 Tim. 2:5). Jesus is the “only-begotten Son of God” (John 1:4). True, Kung’s On Being a Christian, attempts to give some empirical verification of this traditional assertion of the superiority of Christ’s revelation. As I have attempted to show elsewhere, however, serious objections can be raised to his claims that without Christ the other religions cannot really adapt their spiritualities to “modernity”, to the demands of our world-affirming technological age. I am not at all certain, as Kung suggests, that without the gospel the other religions are caught in “unhistoricity, circular thinking, fatalism, unworldliness, pessimism, passivity, caste spirit, social disinterestedness.“

I believe that Kung along with many other Christians, however, is feeling the inadequacy of these traditional claims. I think he is on the brink of suggesting that such claims for the universal finality and normativity of Christ may not be an essential element in the Christian witness to all peoples. Yet, from his conference paper, I am not sure. For instance, when he tells us that “For Christians, Jesus Christ and the Good news he proclaimed are the decisive criteria for faith and conduct, life and death : the definitive Word of God (Heb. 1:1ff.)” and that Christ is “the definitive regulating factor for Christians, for the sake of God and humanity”, is he using the phrase “for Christians” as a restrictive qualifier ? Only for Christians ? Would he be ready to recognize that for Muslims, Muhammad is “the definitive Word of God”? For Buddhists, Buddha is “the definitive regulating factor”. In such a view, Christians and Muslims and Buddhists would still have to witness to each other. Jesus, Muhammad, and Buddha would all have universal relevance for all peoples. But there would be no one, final, normative revelation for all other revelations. If King is saying this, he is saying something different from what he has said in earlier publications. He has crossed a theological Rubicon. But has he ?

Crossing the Rubicon from Inclusivism to Pluralism

I am asking Kung as well as other theologians (e.g., John B. Cobb) — for greater clarity on this “Rubicon question” concerning the uniqueness and finality of Christ. Such clarity is needed by both fellow Christians and non-Christian partners in dialogue. Although Kung echoing Arnold Toynbee, does well to excoriate “the scourge of exclusivism”, is he perhaps unconsciously advocating a more dangerous, because more subtle, scourge of inclusivism ? As Leonard Swidler has pointed out, authentic, real “dialogue can take place only between equals…par cum pari.“

It seems to me that an inclusive christology, which views Christ and Christianity as having to include, fulfill, perfect other religions, is really only a shade away from the theory of “anonymous Christianity” so stoutly criticized by Kung the theory of “inclusive Christianity” may not assert that other believers are already Christians without knowing it ; but it does affirm that these believers must become Christians in order to share in the fullness of revelation and salvation. Kung has called persons of other religions “Christians in spe” (in hope) who must be made “Christians in re” (in fact).

Does Kung will hold to such an inclusive christology and theology of religions ? Does he realize its possible harmful effects on dialogue in the way it implicitly but assuredly subordinates all other religions to Christianity ?

My question takes on a sharper focus in Kung concluding that we stop thinking “in terms of alternatives — Jesus or Muhammad” — and start thinking “in terms of synthesis — Jesus and Muhammad, in the sense that Muhammad himself acts as a witness to Jesus.” I am not sure just how Kung does or can understand that “and”. Is it the “and” of equality (like “Son and Spirit”) or the “and” of subordination (like “law and gospel”)? Previously, Kung would have had to come down, I believe, on the side of final subordination insofar as he has insisted that Christ is God’s final norm for all persons of all times. But I am not sure what he would say today.

My final question is more of a personal request. In asking for more clarity, I am really asking Hans Kung to step across the Rubicon. I believe that his own christology, as well as his own doctrine of God, implicitly allows him to do that. I suspect that the press of interreligious dialogue has also made the possibility of crossing more urgent.

Might I also point out that in making the crossing, he would be in good company. Other Christian thinkers have moved from an earlier inclusivist position of viewing Christianity as the necessary fulfillment and norm for all religions, to a more pluralist model that affirms the possibility that other religions may be just as valid and relevant as Christianity. They have admitted that other religious figures, such as Muhammad, may be carrying out, in very different ways, revelatory, salvific roles analogous to that of Jesus Christ. Among such thinkers are not only Ernst Troeltsch and Arnold Toynbee, but also a number of Christian theologians who have more recently shifted from an inclusivist Christocentrism (Christ at the center) to a pluralist theocentrism (God/the Ultimate in the center): Raimundo Panikkar, Stanley Samartha, John Hick, Rosemary Ruether, Tom Driver, Aloysius Pieris.

Granted Prof. Kung’s respectability and his influence, and given the caution and thoroughness with which he makes all his theological moves, I feel that if he were to cross the Rubicon to a more pluralist theology of religions that does not need to insist on Christ or Christianity as the norm and fulfillment of other religions, he would be, once again, a pioneer leading other Christians to a more open, authentic, and liberative understanding and practice of their faith.

But I ask you, Hans Kung, do you think such a new direction in Christian attitudes toward other religions, such a crossing of the Rubicon, is possible ? And would it be productive of greater Christian faith and dialogue ?