Preamble : Death of Muhammad

Few figures in religious history have left as significant a legacy as the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ, whose teachings profoundly shaped Islamic civilisation. Nevertheless, persistent misconceptions, often stemming from misinterpretations of Quranic verses and hadiths, seek to challenge his integrity. Among these is the notion that divine retribution befell the Prophet ﷺ for alleged falsehoods, as purported by some citing Surah al-Haqqah (Qur’an, 69:44 – 46).

The circumstances surrounding the passing of the Prophet ﷺ have sparked debate, with critics frequently pointing to the alleged death of Muhammad by poisoning as evidence against his prophethood. This article seeks to scrutinize these assertions by meticulously analyzing historical and medical evidence. A rigorous examination of primary Islamic sources and contemporary medical insights aims to elucidate the truth behind such claims, providing clarity and reaffirming the Prophet’s unblemished integrity and prophetic authenticity.

Quranic Analysis : Surah al-Haqqah (Q69:44 – 46)

A. Contextual Interpretation

The verses in question from Surah al-Haqqah state :

وَلَوْ تَقَوَّلَ عَلَيْنَا بَعْضَ الْأَقَاوِيلِ ﴿٤٤﴾ لَأَخَذْنَا مِنْهُ بِالْيَمِينِ ﴿٤٥﴾ ثُمَّ لَقَطَعْنَا مِنْهُ الْوَتِينَ ﴿٤٦

Wa law taqawwala ‘alaynā ba‘ḍa al-aqāwīli (44)

La’akhaẓnā min’hu bi-al-yamīn (45)

Thumma laqaṭa‘nā min’hu al-watīn (46)Translation :

“And if Muhammad had made up about Us some[false] sayings, We would have seized him by the right hand ; Then We would have cut from him the aorta.“1

Critics often misrepresent these verses to suggest that Muhammad (ﷺ) made up divine revelations. However, a closer look shows the hypothetical nature of the clause, making it clear that this scenario did not and could not have occurred. The rhetorical construct serves to emphasize the absolute truthfulness and divine protection given to the Prophet (ﷺ). This severe hypothetical consequence is a testament to the sanctity and integrity of the divine message he conveyed.

Moreover, the Qur’an itself states that the Prophet had completed his mission :

الْيَوْمَ أَكْمَلْتُ لَكُمْ دِينَكُمْ وَأَتْمَمْتُ عَلَيْكُمْ نِعْمَتِي وَرَضِيتُ لَكُمُ الْإِسْلَامَ دِينًا

Al-yawma akmaltu lakum dīnakum wa atmāmtu ‘alaykum ni‘matī wa raḍītu lakumu-l-Islāma dīnaTranslation :

“This day I have perfected for you your religion and completed My favor upon you and have approved for you Islām as religion.“2

Given this declaration of the completion of the religion of Islam, the logic of claiming that he died due to the threat in Surah al-Haqqah (Q 69:44 – 46) is flawed. The completion of his mission contradicts any assertion that his death was a result of divine retribution for falsehood.

Hadith Analysis : The Prophet’s Suffering

The suffering of the Prophet (ﷺ) due to the poisoned meat he consumed at Khaybar is well-documented in Islamic sources. Critics often misinterpret these accounts to suggest a connection with the Quranic warning in Surah al-Haqqah, but a closer examination reveals a different narrative. The hadith reports highlight the Prophet’s immense resilience and the metaphorical language used to describe his suffering, rather than implying any divine retribution.

A. Sahih al-Bukhari and Sunan Abi Dawud

The hadith from Sahih al-Bukhari reports :3

يَا عَائِشَةُ مَا أَزَالُ أَجِدُ أَلَمَ الطَّعَامِ الَّذِي أَكَلْتُ بِخَيْبَرَ، فَهَذَا أَوَانُ وَجَدْتُ انْقِطَاعَ أَبْهَرِي مِنْ ذَلِكَ السَّمِّ

Yā ‘Ā’ishah ! Mā azālu ajidu ʾalam aṭ-ṭa‘ām allaḏī akaltu bi-Khaybar, fa-hādhā awānu wajadtu inqiṭā‘a abharī min dha-l-samm.“O ‘Aisha ! I still feel the pain caused by the food I ate at Khaibar, and at this time, I feel as if my aorta is being cut from that poison.”

Another relevant hadith in Sunan Abi Dawud provides further context :4

حَدَّثَنَا وَهْبُ بْنُ بَقِيَّةَ، عَنْ خَالِدٍ، عَنْ مُحَمَّدِ بْنِ عَمْرٍو، عَنْ أَبِي سَلَمَةَ، عَنْ أَبِي هُرَيْرَةَ، قَالَ كَانَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم يَقْبَلُ الْهَدِيَّةَ وَلاَ يَأْكُلُ الصَّدَقَةَ . وَحَدَّثَنَا وَهْبُ بْنُ بَقِيَّةَ فِي مَوْضِعٍ آخَرَ عَنْ خَالِدٍ عَنْ مُحَمَّدِ بْنِ عَمْرٍو عَنْ أَبِي سَلَمَةَ وَلَمْ يَذْكُرْ أَبَا هُرَيْرَةَ قَالَ كَانَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم يَقْبَلُ الْهَدِيَّةَ وَلاَ يَأْكُلُ الصَّدَقَةَ . زَادَ فَأَهْدَتْ لَهُ يَهُودِيَّةٌ بِخَيْبَرَ شَاةً مَصْلِيَّةً سَمَّتْهَا فَأَكَلَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم مِنْهَا وَأَكَلَ الْقَوْمُ فَقَالَ ” ارْفَعُوا أَيْدِيَكُمْ فَإِنَّهَا أَخْبَرَتْنِي أَنَّهَا مَسْمُومَةٌ ” . فَمَاتَ بِشْرُ بْنُ الْبَرَاءِ بْنِ مَعْرُورٍ الأَنْصَارِيُّ فَأَرْسَلَ إِلَى الْيَهُودِيَّةِ ” مَا حَمَلَكِ عَلَى الَّذِي صَنَعْتِ ” . قَالَتْ إِنْ كُنْتَ نَبِيًّا لَمْ يَضُرَّكَ الَّذِي صَنَعْتُ وَإِنْ كُنْتَ مَلِكًا أَرَحْتُ النَّاسَ مِنْكَ . فَأَمَرَ بِهَا رَسُولُ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم فَقُتِلَتْ ثُمَّ قَالَ فِي وَجَعِهِ الَّذِي مَاتَ فِيهِ ” مَا زِلْتُ أَجِدُ مِنَ الأَكْلَةِ الَّتِي أَكَلْتُ بِخَيْبَرَ فَهَذَا أَوَانُ قَطَعَتْ أَبْهَرِي ” .

Haddathanā Wahbu bnu Baqiyyah, ‘an Khālid, ‘an Muḥammad bni ‘Amr, ‘an Abī Salamah, ‘an Abī Hurayrah, qāla kāna Rasūlu-llāhi ṣalla-llāhu ‘alayhi wa sallam yaqbal al-hadiyyah wa lā ya’kul aṣ-ṣadaqah. Wa haddathanā Wahbu bnu Baqiyyah fī mawḍi‘in ākhara ‘an Khālid, ‘an Muḥammad bni ‘Amr, ‘an Abī Salamah wa lam yadkur Abā Hurayrah, qāla kāna Rasūlu-llāhi ṣalla-llāhu ‘alayhi wa sallam yaqbal al-hadiyyah wa lā ya’kul aṣ-ṣadaqah. Zāda fa-’ahdat lahu yahūdiyyah bi-Khaybar shāh maṣliyah sammathā fa-’akala Rasūlu-llāhi ṣalla-llāhu ‘alayhi wa sallam minhā wa ‘akal al-qawm fa-qāla “irfa‘ū aydiyakum fa-’innahā akhbartanī annahā masmūmah.” Fa-māta Bishr bnu al-Barā’ bnu Ma‘rūr al-Anṣārī fa-’arsala ilā al-yahūdiyyah “mā ḥamalaki ‘alā alladhī ṣana‘tī?” Qālat in kunta nabiyyan lam yaḍurraka alladhī ṣana‘tu wa in kunta malikan araḥtu an-nāsa minka. Fa-’amara bihā Rasūlu-llāhi ṣalla-llāhu ‘alayhi wa sallam fa-qutilat thumma qāla fī waja‘ihi alladhī māta fīhi “mā zilta ajidu mina al-aklah allati akaltu bi-Khaybar fa-hādhā awān qata‘at abharī.”

Narrated Abu Hurairah :

The Messenger of Allah (ﷺ) would accept a present, but would not accept alms (sadaqah)…So a Jewess presented him at Khaybar with a roasted sheep which she had poisoned. The Messenger of Allah (ﷺ) ate of it and the people also ate. He then said : Take away your hands (from the food), for it has informed me that it is poisoned. Bishr ibn al-Bara’ ibn Ma’rur al-Ansari died. So he (the Prophet) sent for the Jewess (and said to her): What motivated you to do the work you have done ? She said : If you were a prophet, it would not harm you ; but if you were a king, I should rid the people of you. The Messenger of Allah (ﷺ) then ordered regarding her and she was killed. He then said about the pain of which he died : I continued to feel pain from the morsel which I had eaten at Khaybar. This is the time when it has cut off my aorta.

These hadiths provide crucial context for understanding the nature of the Prophet’s suffering and its metaphorical implications. They reveal the Prophet’s (ﷺ) resilience and the intense physical pain he endured, reflecting his human vulnerability while emphasizing his steadfast faith and divine mission.

B. Metaphorical Language and Misinterpretations

These hadith narrations describe the Prophet’s (ﷺ) suffering due to poisoned meat he consumed at Khaibar. Critics misinterpret these texts to align with the Quranic warning in Surah al-Haqqah, suggesting falsehood. However, the language used in these hadith is metaphorical, depicting the intense pain the Prophet experienced rather than implying divine retribution.

The poison had immediately killed the Companion, Bishr ibn al-Bara’, but the Prophet (ﷺ) survived for three years, indicating he did not die from the poisoning directly. Historical sources affirm that the Prophet passed away due to a high fever,5 not from poisoning, further discrediting the claim that he died from the poison.

The Jewess responsible for the poisoning acknowledged that had Muhammad (ﷺ) been a false prophet, he would have perished from the poison. Her statement and the Prophet’s survival affirmed his divine protection and true prophethood.

Additionally, it should be noted that the Prophet (ﷺ) lived for approximately three more years after the incident, maintaining a healthy and active life. He participated in battles, continued his daily worship, and exhibited no significant changes in his routine. It is irrational to assert that a fever and migraine experienced three years later were the direct effects of the poison.

Furthermore, the translation of “aorta” in English for both “al-Watīn” and “al-Abhar” is not entirely accurate and fails to capture the precise anatomical and metaphorical nuances intended in the original Arabic. More accurate translations would be “vital artery” for “al-Watīn” and “major artery” for “al-Abhar,” a distinction which we will elaborate upon in a subsequent section.

Historical Context and Sirah Sources

A. Chronology of Events

The poisoning incident at Khaibar occurred three years before the Prophet’s passing. As recorded by Ibn al-Qayyim :

“Indeed, the Prophet ate the meat (poisoned) and he lived for three years (after the event) until he got sick and passed away due to that.“6

Had the Quranic warning intended an immediate death as a consequence of falsehood, the Prophet’s three-year survival post-poisoning invalidates the critics’ allegations. This historical context is crucial for understanding the timing and nature of the Prophet’s suffering.

B. Confirmation from Biographers

Prominent biographers such as Ibn Ishaq and Ibn Hisham document that the Prophet’s death was due to a high fever, not poisoning. These accounts are consistent across multiple historical sources, affirming that the Prophet lived an active life until his final illness, during which he continued to lead prayers and fulfill his responsibilities.

Medical Perspective : Watīn and Abhar

A. Anatomical Clarifications

Understanding the terms “al-Watīn” (الوتين) and “al-Abhar” (الأبهر) is crucial in the context of Qur’anic and hadith literature. These terms refer to significant blood vessels within the human body, and their correct identification is necessary for accurate interpretation of the texts.

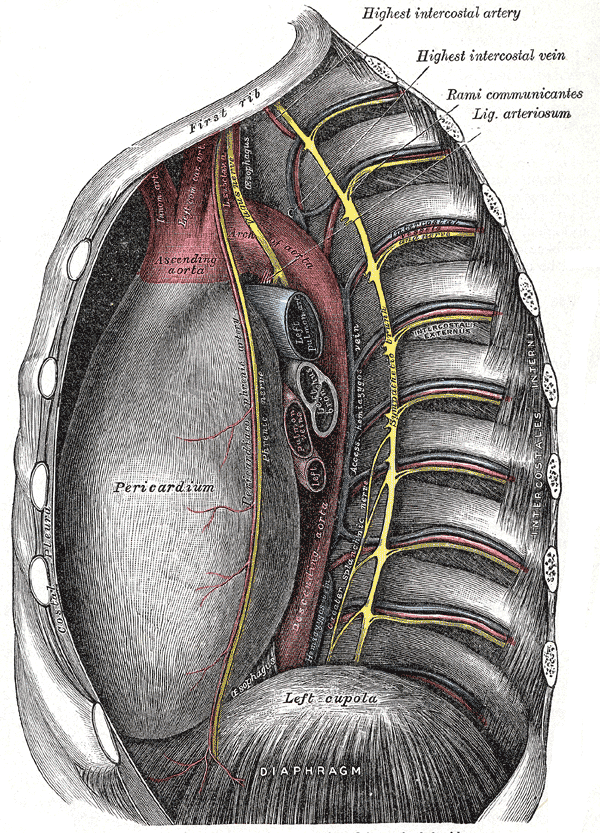

The thoracic aorta, viewed from the left side.7

“Al-Watīn” is commonly translated as the aorta, particularly the thoracic aorta. This translation is misleading as it does not fully capture the essence of the term. The thoracic aorta is the main artery that carries oxygenated blood from the heart to the rest of the body. In modern medical terminology, the thoracic aorta includes the ascending aorta, the aortic arch, and the descending thoracic aorta. However, the term “Al-Watīn” more accurately refers to the vital artery that, if severed, results in immediate death. A more precise translation would be “the life artery” or “vital artery” to convey its critical importance to survival.

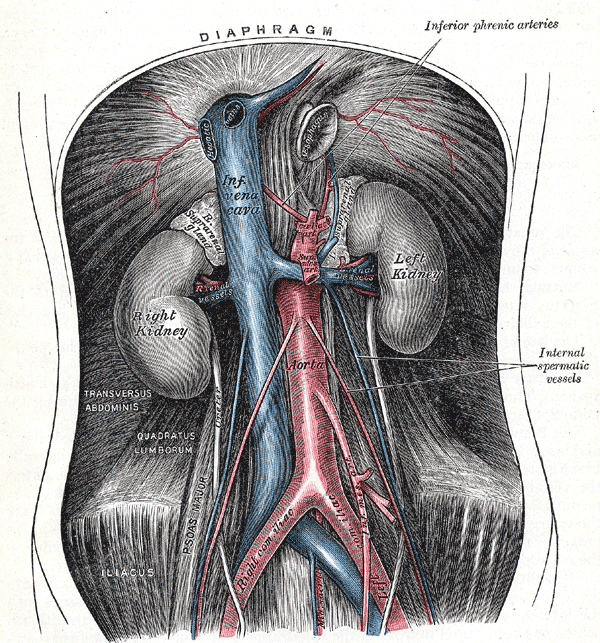

The abdominal aorta and its branches.8

“Al-Abhar,” on the other hand, refers to significant veins or arteries, particularly those in the back or deep within the heart. In modern medical terms, it could refer to the abdominal aorta, which is the continuation of the thoracic aorta as it passes through the diaphragm into the abdomen. The abdominal aorta supplies oxygenated blood to the lower body and vital organs. Recognizing these distinctions clarifies the appropriate contexts in which these terms are used in the Quran and hadith. The term “al-Abhar” should be translated more accurately as “the major artery” or “principal artery” to better reflect its anatomical significance.

Ibn al-Athir explains the term “al-Abhar” as follows :9

فِيهِ « مَا زَالَتْ أكْلَةُ خَيْبَرَ تُعادُّني فَهَذَا أوانُ قَطَعَتْ أَبْهَرِي » الأَبْهَر عِرْقٌ فِي الظَّهْرِ، وَهُمَا أَبْهَرَان. وَقِيلَ هُمَا الْأَكْحَلَانِ اللَّذَانِ فِي الذِّرَاعَيْنِ. وَقِيلَ هُوَ عرقُ مُسْتَبْطِنُ الْقَلْبَ فَإِذَا انْقَطَعَ لَمْ تَبْقَ مَعَهُ حَيَاةٌ. وَقِيلَ الأَبْهَر عِرْقٌ مَنْشَؤُهُ مِنَ الرَّأْسِ وَيَمْتَدُّ إِلَى الْقَدَمِ، وَلَهُ شرايينُ تَتَّصِلُ بِأَكْثَرِ الْأَطْرَافِ وَالْبَدَنِ، فَالَّذِي فِي الرَّأْسِ مِنْهُ يُسَمَّى النّأمَةَ، وَمِنْهُ قَوْلُهُمْ: أسكَتَ اللَّهُ نَأْمَتَهُ أَيْ أَمَاتَهُ، وَيَمْتَدُّ إِلَى الْحَلْقِ فَيُسَمَّى فِيهِ الْوَرِيدَ، وَيَمْتَدُّ إِلَى الصَّدْرِ فيسمَّى الأَبْهَر، وَيَمْتَدُّ إِلَى الظَّهْرِ فيسمَّى الوَتِينَ، والفُؤَادُ معلَّقٌ بِهِ، ويمتدُّ إِلَى الْفَخِذِ فيسمَّى النَّسَا، وَيَمْتَدُّ إِلَى السَّاقِ فيسمَّى الصَّافِنَ. وَالْهَمْزَةُ فِي الْأَبْهَرِ زَائِدَةٌ. وَأَوْرَدْنَاهُ هَاهُنَا لِأَجْلِ اللَّفْظِ. وَيَجُوزُ فِي « أَوَانُ» الضَّمُّ وَالْفَتْحُ: فَالضَّمُّ لِأَنَّهُ خَبَرُ الْمُبْتَدَأِ، وَالْفَتْحُ عَلَى الْبِنَاءِ لِإِضَافَتِهِ إِلَى مَبْنِيٍّ، كَقَوْلِهِ:

Fīhi « mā zālat aklatu Khaybar tuʿāddunī fahādhā awānu qaṭaʿat abharī » al-abhar ʿirq fī al-ẓahr, wa-humā abharān. Wa-qīla humā al-akhalān alladhān fī al-dhirāʿayn. Wa-qīla huwa ʿirq mustabṭin al-qalb fa-idhā inqaṭaʿa lam tabqa maʿahu ḥayāh. Wa-qīla al-abhar ʿirq man sha’uhu min al-raʾs wa-yamtaddu ilā al-qadam, wa-lahu sharāyīn ta-tṭasil bi-akthar al-aṭrāf wa-al-badan, fa-alladhī fī al-raʾs minhu yusammā al-naʾmah, wa-minhu qawluhum : askata-llāhu naʾmatahu ay amātahu, wa-yamtaddu ilā al-ḥalq fa-yusammā fīhi al-warīd, wa-yamtaddu ilā al-ṣadr fa-yusammā al-abhar, wa-yamtaddu ilā al-ẓahr fa-yusammā al-watīn, wa-al-fuʾād muʿallaqun bihi, wa-yamtaddu ilā al-fakhidh fa-yusammā al-nasā, wa-yamtaddu ilā al-sāq fa-yusammā al-ṣāfin. Wa-al-hamzah fī al-abhar zāʾidah. Wa-awrādnāhu hāhunā li-ajli al-lafẓ. Wa-yajūzu fī « awānu » al-ḍammu wa-al-fatḥ : fa-al-ḍammu li-annah khabaru al-mubtadaʾ, wa-al-fatḥu ʿalā al-bināʾ li-iḍāfatihi ilā mabnīn, ka-qawlihi

“In it : ‘The effects of Khaybar’s meal have continued to affect me, and now is the time when it has severed my abhar.’ The abhar is a vein in the back, and they are two abharān. It has also been said that they are the akhal veins in the arms. It is also said to be a vein deep within the heart that, if severed, life cannot continue. It is also said that the abhar is a vein originating from the head and extending to the foot, with arteries connecting to most of the limbs and body. The part in the head is called the naʾmah, and from this comes the phrase ‘askata-llāhu naʾmatahu,’ meaning ‘may Allah silence his naʾmah,’ that is, cause his death. It extends to the throat where it is called the warīd, extends to the chest where it is called the abhar, extends to the back where it is called the watīn, and the heart is connected to it. It also extends to the thigh where it is called the nasā, and extends to the leg where it is called the ṣāfin. The hamzah in al-abhar is extra. We mentioned it here because of the word itself. In ‘awānu,’ both ḍamm and fatḥ are permissible : ḍamm because it is the predicate of the subject, and fatḥ based on its addition to a constructed word, like in the saying :

عَلَي حينَ عاتبْتُ المشيبَ عَلَى الصِّباَ … وَقُلْتُ ألمَّا تَصْحُ وَالشَّيْبُ وَازِعُ

And from the hadith of Ali : ‘‘‘He will be thrown into the void with his two abharān severed.’

Additionally, according to Al-Firuzabadi :10

من القَوْسِ والقِرْبَةِ: مُعَلَّقُهُمَا، ومُعَلَّقُ كُلِّ شيء، أو عِرْقٌ غليظٌ نِيطَ به القَلْبُ إلى الوتينِ

Min al-qaws wa-al-qirbah : mu‘allaquhumā, wa-mu‘allaqu kulli shay’, aw ‘irq ghalīẓ nīṭa bihi al-qalbu ilā al-watīn.

“From the bow and the water skin : their suspension mechanism, and the suspension mechanism of everything, or a thick vein to which the heart is connected to the watīn (the main artery).”

These descriptions clarified that “al-Abhar” can refer to various significant veins or arteries, including the abdominal aorta, while “al-Watīn” specifically refers to the aorta, the main artery essential for survival.

B. Misinterpretations and Metaphors

The Quranic verse in Surah al-Haqqah uses “al-Watīn” metaphorically to emphasize the severity of divine punishment for falsehood, implying the severing of the life source. This term is often mistranslated as “aorta,” but a more precise translation would be “vital artery,” reflecting its critical role in sustaining life. The “vital artery” reflects its necessity for survival, aligning with its function as the main artery that supports systemic circulation.

Conversely, the hadith’s use of “al-Abhar” metaphorically describes the Prophet’s intense pain from the poisoned meat. The translation of “al-Abhar” as “aorta” is not entirely accurate ; it more closely corresponds to a major blood vessel or artery, potentially the abdominal aorta. This misinterpretation fails to capture the anatomical specificity and metaphorical depth intended in the original Arabic. The “major artery” emphasizes its significant role in the circulatory system without the same immediate life-or-death implication as the “vital artery.”

This use of metaphorical language is consistent with Arabic rhetorical traditions, which convey the gravity of physical suffering through vivid expression. Thus, translating both “al-Watīn” and “al-Abhar” as “aorta” in English texts is a mistranslation. More accurate translations would be “vital artery” for “al-Watīn” and “major artery” for “al-Abhar,” ensuring the precise anatomical and metaphorical nuances are preserved.

Explanation of Kinayah

A. Definition and Application

In Arabic rhetoric, kinayah (كناية) denotes a form of metaphorical expression where a phrase or word conveys a meaning indirectly, often implying something deeper or more nuanced than the literal interpretation. Kinayah is extensively used in Arabic literature and speech to illustrate concepts, emotions, or conditions with vivid and emphatic clarity. This rhetorical device is also common in the Quran and hadith, enhancing the depth and impact of the message.

B. Specific Usage in Hadith

In the hadith describing the Prophet’s suffering, the phrase قطع أبهر (“cutting of the abhar”) functions as a kinayah, expressing the intense pain and suffering he endured. It is not intended to be understood literally as the cutting of an anatomical part but rather as a powerful depiction of his agony. The use of kinayah in Arabic serves to convey the seriousness or intensity of a situation, adding layers of meaning to the narrative.

Prophetic Truthfulness

A. Quranic Affirmations

The Quran itself attests to the unwavering truthfulness of Prophet Muhammad (ﷺ):

وَمَا يَنطِقُ عَنِ الْهَوَىٰ

Wa mā yanṭiqu ‘ani-l-hawā.Translation :

“Nor does he speak from [his own] inclination.11

B. Historical Testimonies

The Prophet’s character as Al-Amin (The Trustworthy) was acknowledged even by his adversaries. A well-documented incident involved the Prophet calling the Quraysh tribes to Mount Safa, asking if they would believe him if he warned them of an impending attack, to which they affirmed his truthfulness :12

صَعِدَ النَّبِيُّ صلى الله عليه وسلم عَلَى الصَّفَا فَجَعَلَ يُنَادِي ” يَا بَنِي فِهْرٍ، يَا بَنِي عَدِيٍّ ”. لِبُطُونِ قُرَيْشٍ حَتَّى اجْتَمَعُوا، فَجَعَلَ الرَّجُلُ إِذَا لَمْ يَسْتَطِعْ أَنْ يَخْرُجَ أَرْسَلَ رَسُولاً لِيَنْظُرَ مَا هُوَ، فَجَاءَ أَبُو لَهَبٍ وَقُرَيْشٌ فَقَالَ ” أَرَأَيْتَكُمْ لَوْ أَخْبَرْتُكُمْ أَنَّ خَيْلاً بِالْوَادِي تُرِيدُ أَنْ تُغِيرَ عَلَيْكُمْ، أَكُنْتُمْ مُصَدِّقِيَّ ”. قَالُوا نَعَمْ، مَا جَرَّبْنَا عَلَيْكَ إِلاَّ صِدْقًا. قَالَ ” فَإِنِّي نَذِيرٌ لَكُمْ بَيْنَ يَدَىْ عَذَابٍ شَدِيدٍ ”. فَقَالَ أَبُو لَهَبٍ تَبًّا لَكَ سَائِرَ الْيَوْمِ، أَلِهَذَا جَمَعْتَنَا

Ṣa‘ida an-nabiyyu ṣallā-llāhu ‘alayhi wa sallam ‘ala aṣ-Ṣafā fa-ja‘ala yunādī “Yā Banī Fihr, Yā Banī ‘Adī!” li-buṭūni Quraysh ḥattā ijtama‘ū, fa-ja‘ala ar-rajulu idhā lam yastaṭi‘ an yakhruja arsala rasūlan li-yanẓura mā huwa, fa-jā’a Abū Lahab wa-Quraysh fa-qāla “ara’aytakum law akhbartukum anna khaylan bi-al-wādī turīdu an tughyra ‘alaykum, akuntum muṣaddiqiyya?” Qālū na‘am, mā jarrabnā ‘alayka illā ṣidqan. Qāla “fa-innī nadhīrun lakum bayna yaday ‘adhābin shadīd.” Fa-qāla Abū Lahab tabban laka sā’ira al-yawmi, a‑lihādhā jama‘tanā

Translation :

“When the Verse : ‘And warn your tribe of near-kindred,’ was revealed, the Prophet (ﷺ) ascended the Safa (mountain) and started calling, ‘O Bani Fihr ! O Bani ‘Adi!’ addressing various tribes of Quraish till they were assembled. Those who could not come themselves, sent their messengers to see what was there. Abu Lahab and other people from Quraish came and the Prophet (ﷺ) then said, ‘Suppose I told you that there is an (enemy) cavalry in the valley intending to attack you, would you believe me?’ They said, ‘Yes, for we have not found you telling anything other than the truth.’ He then said, ‘I am a warner to you in face of a terrific punishment.’ Abu Lahab said (to the Prophet) ‘May your hands perish all this day. Is it for this purpose you have gathered us?’ ”

Theological Implications

A. Divine Protection and Prophetic Integrity

The Quranic verse in Surah al-Haqqah reinforces the Prophet’s authenticity by presenting a hypothetical scenario that never occurred. The concept of divine protection (ismah) in Islam holds that prophets are safeguarded from sin and falsehood, supporting the argument against these baseless allegations.

B. Comparison with Biblical Criteria for False Prophets

The Bible outlines specific signs of false prophets, including :

False Prophecies

- “But a prophet who presumes to speak in my name anything I have not commanded, or a prophet who speaks in the name of other gods, is to be put to death.” (Deuteronomy 18:20)

- “When a prophet speaks in the name of the Lord and the thing does not happen or come true, that is a message the Lord has not spoken.” (Deuteronomy 18:22)

Leading People Astray

“If a prophet, or one who foretells by dreams, appears among you and announces to you a sign or wonder, and if the sign or wonder spoken of takes place, and the prophet says, ‘Let us follow other gods’ (gods you have not known) and let us worship them, you must not listen to the words of that prophet or dreamer.” (Deuteronomy 13:1 – 3)

Immoral Behavior

“But the prophet who speaks presumptuously in my name anything I have not commanded, or a prophet who speaks in the name of other gods, that prophet shall die.” (Deuteronomy 18:20)

Inconsistency with Previous Revelation

“To the law and to the testimony ! If they do not speak according to this word, it is because they have no dawn.” (Isaiah 8:20)

Prophet Muhammad (ﷺ) does not fit any of these criteria. His prophecies were accurate, he led people to the worship of the One God, his character was impeccable, and his message was consistent with previous revelations.

C. Consistency, Prophethood, and the Problem of Selective Tests

If Deuteronomy and Isaiah are to be treated as binding criteria for identifying false religious claimants, then methodological integrity requires that these standards be applied consistently rather than selectively. When this consistency test is applied beyond Islam, the contrast between Prophet Muhammad (ﷺ) and Paul of Tarsus becomes instructive.

Paul’s authority rests almost entirely on a private revelatory experience, which he explicitly distinguishes from any transmission received through prior apostolic channels.13 His theological programme is widely recognised — within Christian scholarship itself — as introducing substantive departures from earlier law-centred revelation, particularly in matters of Mosaic law and justification.

By contrast, Prophet Muhammad’s (ﷺ) message was proclaimed publicly, transmitted verbatim, continuously scrutinised by followers and opponents alike, and explicitly presented as a reaffirmation of uncompromising monotheism in continuity with earlier prophets.

Significantly, the New Testament itself does not narrate Paul’s death. Acts concludes with Paul alive and preaching in Rome (Acts 28:30 – 31), and the only passage commonly cited near the end of his life employs metaphorical, cultic language rather than historical description :

“For I am already being poured out like a drink offering, and the time for my departure has come” 14

Claims about Paul’s execution, therefore, rest not on Scripture but on later ecclesiastical tradition. The earliest source, 1 Clement (c. 96 CE), refers to Paul’s martyrdom without specifying the manner of death.15 The explicit claim that Paul was executed by beheading appears only in fourth-century historiography, most notably in Eusebius16 and Jerome17, who associate his death with Nero’s persecution. Whether or not one accepts the full details of this tradition, the essential point remains that Paul’s end is reconstructed retrospectively rather than narrated by revelation.

When these facts are set alongside the biblical criteria themselves, the asymmetry in polemical application becomes evident. Deuteronomy warns against figures who introduce teachings that deviate from prior revelation18, who speak presumptuously in God’s name19, or whose message fails the test of continuity with established law and testimony20. These warnings are rarely turned inward toward Pauline authority, despite long-standing debates over the scope and legitimacy of his theological innovations. Instead, the criteria are selectively externalised and aimed at Islam.

This inconsistency becomes even more pronounced when critics attempt to collapse the Prophet’s (ﷺ) final illness into the Qur’anic warning of Surah al-Haqqah (69:44 – 46). That passage presents a counterfactual threat : if the Messenger were to fabricate revelation, then God would seize him and sever the watīn. Its rhetorical force lies precisely in its hypothetical structure, functioning as a guarantee of authenticity rather than a veiled prediction.

Historically, however, the Prophet (ﷺ) completed his mission, lived for years after the Khaybar incident, and passed away following an acute febrile illness while describing residual pain in the idiom of kinayah. Nothing in this sequence resembles the immediate, decisive divine punishment envisaged in Q69:44 – 46. To claim fulfilment here requires collapsing conditional rhetoric into retrospective prophecy, metaphor into anatomy, and a human poisoning attempt into divine judgement — moves that are linguistically, chronologically, and theologically unsustainable.

The irony deepens when Galatians 1:8 is invoked as a final weapon against Islam :

“Even if we or an angel from heaven should preach a gospel other than the one we preached to you, let him be accursed.”

This verse is routinely deployed to pre-emptively invalidate any subsequent revelation, yet it rests entirely on Paul’s own solitary revelatory authority. In effect, it functions as a self-sealing mechanism that insulates Pauline theology from all later claims, regardless of their continuity with earlier prophetic monotheism.

The Qur’anic model, by contrast, does not immunise Muhammad (ﷺ) from scrutiny ; it exposes him to the severest conceivable consequence if he were to fabricate revelation. The selective invocation of Galatians 1:8 against Islam, while ignoring its circular logic and its dependence on Paul’s private revelation, mirrors the same methodological inconsistency already evident in the use of Deuteronomy and Isaiah.

Some Polemical Observations

It is important to note how polemical presentations often combine three separate issues into one accusation : the historical backdrop to Khaybar, the poisoning incident itself, and the Prophet’s final illness in Madinah. The argument typically depends on sliding between these themes as though they were one continuous proof. Yet the Qur’anic claim (Q69:44 – 46) is a conditional warning about fabricating revelation ; the Khaybar reports concern an attempted poisoning within a particular historical moment ; and the Prophet’s final illness is described in the sources as a distinct febrile episode.

One recurring framing asserts that the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah was a humiliating failure, that Qur’an 48:1 was a “convenient revelation” to save face, and that Khaybar was therefore a substitute target for “booty.” This rhetorical chain is not an argument about the Prophet’s death ; it is an attempt to recast his political judgement as opportunism, and then use that framing to pre-load the poisoning narrative with moral insinuations. Even if a critic persuades an audience that Hudaybiyyah looked unfavourable on the day it was signed, it still does not follow that :

(i) a poisoning three years earlier “proves” imposture, or

(ii) the Qur’anic conditional threat in 69:44 – 46 was realised.

The core evidentiary question remains medical and linguistic : did the Prophet die from an immediate severing of the watīn as punitive judgement, or did he die after an acute febrile illness while describing residual pain in the idiom of kinayah ?

Another recurrent move is to inflate the poisoning account into a “prophethood test” with a rigid rule : “a true prophet must detect poison before tasting it ; otherwise he is false.” This rule is not supplied by the Qur’an, nor by the hadith corpus itself as a doctrinal criterion. In the Sunni hadith framing cited later, the woman’s intention was precisely to see whether he was a prophet or a king, but her private intention does not become a binding standard for what prophethood must look like.

More importantly, the reports do not depict total ignorance that persists until after consumption. They present a sequence in which he tasted, recognised, and stopped others ; one companion died quickly ; the Prophet lived on for years ; and later described pain in a metaphor that classical lexicographers do not treat as a literal anatomical claim. That sequence is compatible with a human experience of tasting harmful food and then halting ingestion, which is exactly why the linguistic treatment of abhar versus watīn matters : the polemical argument depends on collapsing the two into one “aorta-cutting” literalism.

A further move is to stack grisly allegations about Khaybar — executions, torture, enslavement, marriage to Ṣafiyyah—then treat the poisoning as a kind of moral payback that “explains” his death. Whatever one’s ethical judgement about seventh-century warfare, this is still not proof of divine retribution under Q69:44 – 46. The Qur’anic passage is about fabricating revelation ; it does not say, “If you fight X group, We will kill you by poison.” The ethical debate about Khaybar can be discussed on its own terms, but it is methodologically invalid to use it as a shortcut to a claim about Qur’anic falsification.

It is also common to argue that because the Prophet sought treatment—ruqyah by al-Mu‘awwidhatayn, cupping, medicine — this proves he did not believe God willed his death, or that divine protection “failed.” This misreads how classical theism treats means (asbāb). In Islamic theology and practice, taking lawful means is not the negation of trust in God ; it is part of human responsibility. People eat to live and still believe God is al-Razzāq ; they seek medicine and still believe healing is from God. The hadith material about ruqyah and treatment therefore does not function as an admission of “game is up,” but as ordinary prophetic practice that teaches the community how to act under illness.

Finally, polemical presentations often shift from “poison proves he was not a prophet” to a second claim : “his death caused political confusion ; therefore God did not protect the community ; therefore Islam is false.” This is a separate argument altogether and relies on a theological assumption that revelation must always prevent political contestation. Even within the Bible, communities fracture after prophets ; that fact is not normally treated as proof that the prophet was false. The Sunni-Shi‘a split cannot be used as a retrospective test for whether a prophet was genuine unless the critic is willing to apply the same standard consistently across religious history.

Conclusions

The misconception that Prophet Muhammad (ﷺ) suffered before his death due to lying is a gross misinterpretation of Qur’anic and hadith texts. Historical context, linguistic analysis, and theological principles affirm the Prophet’s unwavering truthfulness. The Qur’anic verse in Surah al-Haqqah and the hadiths describing the Prophet’s suffering are distinct in their contexts. The Prophet’s impeccable character, validated by historical records and acknowledged by his adversaries, refutes these baseless allegations.

A detailed look at the Biblical criteria for false prophets further supports the authenticity of Prophet Muhammad (ﷺ). His accurate prophecies, adherence to monotheism, moral integrity, and consistency with previous revelations align with the true characteristics of prophets.

And most certainly, only God knows best !

Appendix : Historically Plausible Poisons in 7th-Century Arabia

Any assessment of the Khaybar poisoning must be restricted to substances that were locally available, commonly known, or realistically obtainable through regional trade in the Hijaz during the 7th century. When this constraint is applied, the range of plausible poisons narrows sharply. Crucially, none of them support the claim of a poison remaining dormant for years and then causing death.

The incident itself is preserved in multiple hadith reports, which consistently describe immediate recognition of poisoning, acute effects on those who consumed the meat, and the prevention of further ingestion once the danger became apparent. One Companion, Bishr ibn al-Barāʾ, is reported to have died from the poisoned meat, while the Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ tasted it and refrained from continuing. This establishes the episode as an acute poisoning attempt, not a delayed or cumulative exposure.

A later narration from ʿĀʾishah reports that during the Prophet’s final illness, he recalled pain associated with what he had eaten at Khaybar and expressed it figuratively as feeling “as if my aorta is being cut.” Similar wording appears elsewhere. This expression is experiential and rhetorical, not a medical diagnosis or toxicological explanation for the cause of death.

The decisive question, therefore, is whether any poison realistically accessible in 7th-century Arabia could remain inert for three to four years and then suddenly cause death without an intervening pathological course.

1. Colocynth (Citrullus colocynthis, bitter apple)

Colocynth is the strongest candidate historically. It is native to Arabia and widely known in pre-Islamic and early Islamic medicine as a powerful purgative that becomes dangerous when misused. No trade network or specialist knowledge would have been required to obtain or deploy it.

It causes severe gastrointestinal irritation, including abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, dehydration, and shock, with onset within hours of ingestion. Survival beyond the acute episode does not lead to delayed fatal collapse. Colocynth has no cumulative or latent toxic mechanism.

2. Arsenic (inorganic arsenic compounds)

Arsenic was a well-known poison in antiquity and could realistically have been obtained through regional trade networks linking Arabia with Persia, Yemen, and the Levant. It required no sophisticated preparation and was historically used for both poisoning and medicine.

Acute arsenic poisoning produces severe gastrointestinal symptoms and systemic collapse within hours to days. Chronic arsenic poisoning, by contrast, requires repeated or sustained exposure and manifests through continuous multisystem damage affecting the skin, nerves, liver, and cardiovascular system. A single exposure that allows survival would not remain biologically inert for years and then suddenly become fatal.

3. Hemlock-type neurotoxins (Conium maculatum or related plants)

Hemlock and similar neurotoxic plants were known throughout the Near East via Jewish and Greco-Roman medical traditions. While not native to the Hijaz, knowledge of such poisons and limited access are historically plausible, particularly in a Jewish settlement such as Khaybar.

Hemlock causes ascending neuromuscular paralysis, leading to respiratory failure in severe cases. Death occurs within hours to days, depending on dosage, and survivors exhibit clear and progressive neurological symptoms. There is no mechanism for silent persistence over multiple years.

4. Lead compounds

Lead exposure was common in antiquity through vessels, glazes, and medicinal preparations, making accidental or intentional ingestion possible.

Acute lead poisoning causes abdominal pain and neurological symptoms, while chronic lead poisoning requires sustained exposure and manifests with ongoing cognitive, gastrointestinal, and renal pathology. A single exposure cannot explain sudden death years later without continuous symptoms, which are absent from the historical record.

5. Mercury compounds

Mercury was known in ancient medicinal and alchemical contexts and could have been accessed indirectly, but it is the least plausible candidate in this context.

Mercury toxicity is characteristically chronic, requiring repeated exposure and producing progressive neurological deterioration, tremors, and behavioral changes. There is no evidence for a one-time dose remaining inert for years and then becoming fatal without a prolonged and obvious disease course.

Medical and historical assessment

Across the five most realistic poison candidates available in or accessible to 7th-century Arabia — desert plants, traded mineral toxins, heavy metals, and regionally known neurotoxins — there is no medically-documented substance that fits the polemical requirement of :

a single ingestion → minimal immediate effect → multi-year dormancy → sudden death

Toxicology operates according to only three patterns :

- Acute lethality (hours – days),

- Chronic illness with continuous symptoms (requiring repeated exposure), or

- Non-lethal survival once the acute phase passes.

There is no fourth category that allows a poison to “wait” several years before acting decisively.

Concluding remarks

Given the types of poisons known in the 7th century and their typical effects, the claim that the Khaybar poisoning lingered for three to four years and then killed the Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ is neither medically nor historically defensible. The sources describe an interrupted human poisoning attempt, not a delayed execution. Qurʾān 69:44 – 46 does not envision a slow, latent, or ambiguous outcome ; it sets forth a counterfactual threat of immediate and decisive divine action — public seizure and the cutting of the watīn—if fabrication had occurred.

The Khaybar episode, by contrast, involved acute effects, cessation of ingestion, and a death years later from natural causes. No poison realistically accessible in 7th-century Arabia can bridge these two frameworks. To insist otherwise is to collapse a conditional divine judgement into a delayed biological process, importing polemics back into both toxicology and the Qurʾānic text. The two are categorically distinct and cannot be coherently conflated.

Frequently-Asked Questions : The Death of Muhammad — Cause, Date, and Aftermath

If Muhammad were a real prophet of God, why didn’t he detect the poison before he ate it ?

This objection rests on a premise that Islam does not accept. Prophethood does not entail omniscience or immunity from harm. The decisive issue is whether the death of Muhammad corresponds to the Qur’anic warning in Q69:44 – 46. It does not. That passage presents a counterfactual threat of immediate divine punishment if fabrication occurred. Historically, the death of Muhammad followed illness and natural decline. Eating a poisoned morsel does not explain what was the result of the death of Muhammad, nor does it establish false prophethood.

If it was God’s will for Muhammad to have eaten the poison, why did he seek treatment and try to recover ? Even Gabriel prayed for him to get better.

Seeking treatment is encouraged in Islam and does not contradict divine decree. Prophets pray, seek healing, and still die. Prayer is worship, not a guarantee of outcome. The cause of death of Muhammad cannot be inferred from unanswered supplication, nor does this define the Muhammad cause of death. This distinction is essential when examining what was the result of the death of Muhammad historically and theologically.

Why would Gabriel pray if Allah had already decreed death ? Does this mean Gabriel did not know Allah’s will ?

Islam does not teach that angels possess independent or total knowledge of divine decree. Angels act within roles permitted to them. Supplication can coexist with a decreed end. Prayer occurring does not negate death occurring. This applies equally when discussing the death of Muhammad and does not redefine the death date of Muhammad or the date of Muhammad’s death as punitive.

Why did Muhammad require others to drink the same medicine he was given, including someone who was fasting ? Doesn’t this seem vindictive ?

The episode is best understood as a deterrent against forcibly medicating him again after he had objected. Even if judged critically, this remains an ethical or leadership issue. It does not establish the cause of Muhammad death, nor does it clarify the Muhammad date of death. Ethical judgments must not be conflated with claims about prophethood.

Why did Muhammad warn against graves becoming places of worship near death instead of praying for guidance for others ? Was this a curse ?

The statements target specific religious practices, particularly grave-veneration and sacralisation of burial sites. They function as doctrinal warnings consistent with anti-idolatry themes. These remarks, often cited as the death bed words of Muhammad, are not expressions of jealousy or bitterness. They do not alter the age of Muhammad’s death or undermine the meaning of the death of Muhammad.

Why is pleurisy sometimes linked to “Satan” in reports, while poisoning is not ?

Such phrasing is not a medical diagnosis. It may reflect rejection of a circulating label or superstition. Even taken literally, it does not establish the cause of death of Muhammad or fix the Muhammad cause of death as poisoning. Nor does it explain what was the result of the death of Muhammad doctrinally or historically.

Did the so-called “prophet test” (poisoning) prove Muhammad was not a prophet because he ate from it ?

No. The test assumes a premise Islam never claimed : that a prophet must always be forewarned of danger or immune from harm. An argument built on an external premise cannot refute Islamic doctrine. The death of Muhammad cannot be measured by immunity standards borrowed from other traditions, nor does it redefine the death date of Muhammad as divine punishment.

Does the statement “I feel my abhar is being cut” mean Qur’an 69’s watīn was fulfilled ?

No. Qur’an 69 uses watīn in a counterfactual divine-punishment formula. The hadith uses abhar as vivid pain language. Equating both as “aorta” is translation flattening, not proof. This linguistic distinction is crucial when discussing the date of Muhammad’s death and rejecting claims that Qur’an 69 was “executed” at the death of Muhammad.

Does the moral indictment of Khaybar prove false prophethood ?

No. Historical and ethical debates must stand on their own terms. Even the harshest framing of Khaybar does not establish Qur’anic fabrication or determine the cause of Muhammad’s death. Moral critique does not explain what was the result of the death of Muhammad in terms of doctrine or scripture.

If figures in other scriptures survived poison or venom, why didn’t Muhammad ?

Cross-scriptural comparisons are theological arguments, not historical proofs. They often assume that divine favor guarantees physical immunity — an assumption not consistently taught in Islamic or biblical history. Such comparisons do not resolve questions about the Muhammad date of death or the age of Muhammad’s death.

If Muhammad did not clearly name a successor, doesn’t later division show lack of divine protection ?

No. Political succession disputes are part of human history. After the death of Muhammad, disagreements over leadership emerged, as they have after other major figures. The aftermath of Muhammad’s death reflects political contestation, not false prophethood or doctrinal failure.

Did Muhammad die suddenly, proving he was poisoned to death ?

The sources describe a severe final illness, not a sudden, unexplained collapse. They do not provide a modern clinical autopsy, nor do they conclusively establish the cause of death of Muhammad. What they do not justify is the claim that Qur’an 69 was “executed” at his death. That conclusion ignores the death date of Muhammad, the date of Muhammad’s death, and the broader historical record after the death of Muhammad.

- Surah al-Haqqah, 69:44 – 46[⤶]

- Surah al-Ma’idah, 5:3[⤶]

- Sahih al-Bukhari, 4428[⤶]

- Sunan Abi Dawud, 4512[⤶]

- Welch speculates that Muhammad’s death was caused by Medinan fever, which was aggravated by physical and mental fatigue. See : Frants Buhl, & Alford T. Welch (1993). “Muḥammad”. Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. 7 (2nd ed.). Brill. pp. 360 – 376[⤶]

- Ibn al-Qayyim. Zad al-Ma’ad, 3.298[⤶]

- Figure 530 : Anatomy of the Human Body, Bartleby.[⤶]

- Figure 531 : Anatomy of the Human Body, Bartleby.[⤶]

- Ibn al-Athir, Kitab al-Nihayah fi Gharib al-Hadith wa al-Athar, 1.18[⤶]

- Al-Firuzabadi, Al-Qamus al-Muhit, 691[⤶]

- Surah al-Najm, 53:3[⤶]

- Sahih al-Bukhari, 4770[⤶]

- See Acts 9:3 – 6 ; Galatians 1:11 – 12 ; 1:16 – 17[⤶]

- 2 Timothy 4:6[⤶]

- 1 Clement 5.5 – 7[⤶]

- Ecclesiastical History 2.25.5 – 8[⤶]

- De Viris Illustribus §5[⤶]

- Deuteronomy 13:1 – 3[⤶]

- Deuteronomy 18:20[⤶]

- Isaiah 8:20[⤶]