In Memoriam

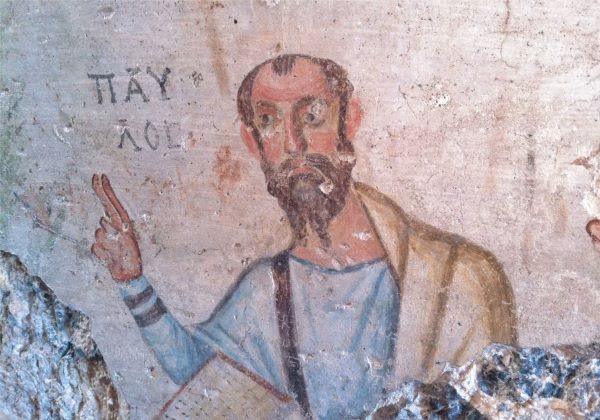

We are deeply saddened by the passing of Dr. Dale B. Martin in November 2023. Before his death, Dr. Martin entrusted me with two draft files of his research on Paul of Tarsus. These drafts explore the contradictions between the letters of Paul and Acts, showcasing his original work. Unfortunately, Dr. Martin could not complete them. This article is written in tribute to his legacy, with authorship attributed to Dr. Dale B. Martin.

Content Overview

- 1 In Memoriam

- 2 I. Introduction

- 3 II. Historical Context

- 4 III. Authorship and Reliability

- 5 IV. Main Argument

- 6 V. Differences in Chronology and Geography

- 7 VI. Differences in Missionary Practices

- 8 VII. Differences in Public Speaking and Rhetoric

- 9 VIII. Differences in Identity and Mission

- 10 IX. Direct Contradictions

- 11 X. Conclusion

I. Introduction

In studying early Christianity, it is crucial to carefully examine the sources that describe the lives and teachings of its key figures. Paul the Apostle is a central figure, not only for his major contributions to the New Testament but also for his lasting impact on early Christian theology. However, there is a significant difference between the portrayal of Paul in his own letters and the depiction found in the Acts of the Apostles. This essay aims to critically analyze these contradictions, explaining their implications for our understanding of Paul’s life, mission, and lasting influence.

II. Historical Context

Understanding the historical context of Paul’s life is crucial for analyzing the contradictions between his letters and Acts. Paul lived during the first century CE, a period marked by Roman rule, Jewish unrest, and the spread of Hellenistic culture. This environment influenced his ministry, interactions, and the way his story was recorded. Knowing the social, political, and cultural background of this period helps us understand the different perspectives presented in Paul’s letters and the Acts of the Apostles.

The claim that the Gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles were written by the same person, traditionally known as Luke, needs careful reconsideration. The name “Luke” is just a placeholder, reflecting our uncertainty about who actually wrote these texts. This ambiguity is highlighted by the lack of direct evidence linking the “Luke” mentioned in the New Testament with the author of Luke-Acts. Scholars have long debated the authorship of these texts, and this debate continues to have implications for how we interpret their content and reliability.

Furthermore, the dating of Luke-Acts is also a matter of scholarly debate. Most scholars agree that these texts were written several decades after the events they describe, which raises questions about their historical accuracy. The distance in time between the events and their recording means that the author of Luke-Acts may have relied on oral traditions and secondhand accounts, which could introduce inconsistencies and biases. This makes it essential to critically assess the reliability of these texts in comparison to the letters of Paul.

B. Paul’s Letters as Authentic Sources

In contrast, the authorship of Paul’s letters is widely accepted among scholars, with a consensus that at least seven of the letters attributed to Paul were indeed written by him. This consensus makes Paul’s letters more reliable for historical analysis, providing firsthand accounts of his thoughts, activities, and theological positions. Paul’s letters were written closer in time to the events they describe, which enhances their value as historical documents.

The letters of Paul are considered primary sources, as they offer direct insight into his ministry and the issues facing early Christian communities. These letters address specific situations and controversies, providing a window into the lived experiences of early Christians. By examining Paul’s letters alongside the accounts in Acts, we can gain a more nuanced understanding of his life and work, and the broader context of early Christianity.

IV. Main Argument

The main goal of this exploration is to highlight the clear differences between the historical Paul, as shown in his letters, and the Paul presented in Acts. This distinction is important for understanding the theological and literary variations within early Christian texts. By examining these differences, we gain a better understanding of the complexities in early Christian history and theology. The portrayal of Paul in Acts often reflects the theological and narrative goals of the author, which can differ significantly from the self-representation in Paul’s letters.

These differences are not merely superficial but reflect deeper theological and ideological divergences. For example, the depiction of Paul’s interactions with other apostles and Jewish communities varies between the two sources, highlighting different perspectives on the relationship between early Christianity and Judaism. By analyzing these discrepancies, we can better understand the diverse theological landscapes of the early Christian movement and the ways in which different authors shaped their narratives to serve specific purposes.

V. Differences in Chronology and Geography

A. Paul’s Conversion and Early Ministry

Paul’s Own Account

In his letters, particularly in Galatians, Paul describes his conversion experience as occurring in Damascus, followed by a stay in Arabia before returning to Damascus. He emphasizes his independence from the Jerusalem apostles, showing a journey marked by direct divine revelation and a personal prophetic calling (Gal 1:15 – 17). Paul’s account stresses his unique calling and mission, which he believes were given directly by God without the mediation of other apostles.

This emphasis on independence is significant because it highlights Paul’s self-perception as an authoritative figure in his own right. It also reflects his tension with other early Christian leaders, particularly those based in Jerusalem. By presenting his conversion and mission in this way, Paul asserts his legitimacy and the divine origin of his message, setting the stage for his later conflicts and collaborations with other apostles.

Acts of the Apostles

On the other hand, Acts presents a different sequence. According to Acts, Paul’s conversion happens on the road to Damascus after a period of persecuting Christians in Jerusalem. This story places Paul’s early activities within a different geographical and chronological framework, suggesting that theological and literary reasons shaped this account (Acts 9:1 – 19). The narrative in Acts emphasizes the dramatic nature of Paul’s conversion and his immediate integration into the Christian community.

The account in Acts portrays Paul as having a more collaborative relationship with the Jerusalem apostles from the outset. This portrayal serves to align Paul more closely with the established leadership of the early church and to emphasize unity within the Christian movement. By depicting Paul in this way, the author of Acts may be attempting to present a more harmonious picture of early Christianity, minimizing conflicts and divisions.

B. Implications of Discrepancies

The differences between these accounts are not minor. The closer chronological proximity of Paul’s letters, written within two decades of the events they describe, gives them greater historical weight compared to Acts, which was written several decades later. This time gap, along with the anonymous authorship of Acts, highlights the need for a critical evaluation of its historical reliability. The discrepancies between the two sources raise important questions about the nature of early Christian history and the construction of its narratives.

Understanding these differences allows us to see how early Christian communities remembered and reshaped their past. The variations in the accounts reflect different theological agendas and historical contexts, revealing the dynamic and contested nature of early Christian identity. By critically examining these discrepancies, we can better appreciate the diversity of early Christianity and the ways in which its history was constructed and transmitted.

VI. Differences in Missionary Practices

A. Initial Preaching and Audience

Depiction by Paul and Acts

Acts consistently shows Paul as initially preaching to Jews in synagogues, facing rejection, and then turning to gentiles. This pattern of addressing Jews first and then shifting focus to gentiles appears throughout Acts, aligning with the broader theological theme of the gospel’s transition from Jews to gentiles (Acts 13:14 – 46 ; 18:4 – 6). The narrative in Acts emphasizes Paul’s efforts to reach out to his fellow Jews and his subsequent mission to the gentiles as a response to Jewish rejection.

This portrayal serves to highlight the universal scope of Paul’s mission and the spread of Christianity beyond its Jewish origins. By showing Paul engaging with both Jewish and gentile audiences, Acts underscores the inclusive nature of the Christian message and its appeal to diverse communities. This narrative structure also reinforces the legitimacy of the gentile mission and its continuity with the Jewish roots of Christianity.

Paul’s Letters

In stark contrast, Paul’s letters show a different strategy. Paul consistently identifies himself as the “apostle to the gentiles,” emphasizing his mission to non-Jews. His letters show little focus on initial efforts among Jews, highlighting a more direct approach to gentile evangelism (Gal 2:7 – 9). Paul’s self-identification as the apostle to the gentiles reflects his theological conviction that his mission was divinely ordained and central to the spread of the gospel.

Paul’s letters reveal his deep commitment to reaching gentile audiences and his belief in the importance of their inclusion in the Christian community. This focus on gentile evangelism is a key aspect of Paul’s identity and mission, shaping his theological arguments and his interactions with other Christian leaders. By emphasizing his role as the apostle to the gentiles, Paul differentiates his mission from those of other apostles and underscores the unique nature of his calling.

B. Patterns of Rejection and Acceptance

The story in Acts, where Paul’s message is rejected by Jews and then accepted by gentiles, serves a theological purpose, illustrating the spread of the gospel. However, Paul’s own writings do not show this pattern, suggesting a more straightforward mission to the gentiles without the intermediate step of preaching to Jews first. Paul’s letters depict a more direct and immediate engagement with gentile communities, reflecting his focus on their conversion and inclusion in the Christian faith.

The differences in these patterns of rejection and acceptance highlight the distinct theological agendas of the two sources. Acts emphasizes the transition from Jewish to gentile audiences as part of the broader narrative of Christian expansion, while Paul’s letters focus more narrowly on his specific mission and its theological implications. By examining these differing accounts, we can gain a deeper understanding of the diverse ways in which early Christians understood and represented their mission.

VII. Differences in Public Speaking and Rhetoric

A. Paul as a Public Speaker

Portrayal in Acts

Acts shows Paul as a skilled speaker, delivering powerful speeches in both Greek and Hebrew, and respected as a Roman citizen. This portrayal aligns with the classical ideal of a noble, eloquent public figure (Acts 21:40 ; 26:1 – 29). The depiction of Paul as a confident and articulate orator serves to enhance his credibility and authority as a leader within the early Christian movement.

By presenting Paul as a skilled rhetorician, Acts reinforces his role as a persuasive and influential figure capable of addressing diverse audiences. This portrayal also aligns with the broader narrative strategy of Acts, which seeks to present a cohesive and compelling account of the spread of Christianity. The emphasis on Paul’s public speaking abilities underscores the importance of effective communication in the early church’s missionary efforts.

Paul’s Self-Depiction

In his letters, Paul presents a more humble and self-critical image. He admits to weak public speaking skills and physical frailties, showing a dramatically different picture from the polished orator depicted in Acts. For instance, Paul acknowledges that his “bodily presence is weak, and his speech contemptible” (2 Cor 10:10). This self-depiction reflects Paul’s theological emphasis on the power of the gospel rather than the abilities of the messenger.

Paul’s candid self-assessment serves to highlight his reliance on divine strength rather than personal skill. By presenting himself as weak and unassuming, Paul underscores the transformative power of the gospel and the role of God’s grace in his ministry. This portrayal contrasts sharply with the more heroic image in Acts, offering a different perspective on Paul’s identity and mission.

B. Impact on Paul’s Image

This contrast between the noble, eloquent Paul in Acts and the humble, struggling Paul in his letters is significant. The candid self-assessment in his letters offers a more personal and arguably more historically accurate view of Paul’s public persona. It reflects a man aware of his limitations, yet steadfast in his mission. Paul’s humility and self-awareness add depth to our understanding of his character and motivations.

The differing portrayals also highlight the diverse ways in which early Christians constructed and communicated their identities. Acts presents a more idealized and cohesive narrative, while Paul’s letters offer a more nuanced and introspective account. By comparing these different images of Paul, we can gain a richer understanding of his life and legacy, and the complex nature of early Christian identity formation.

VIII. Differences in Identity and Mission

A. Conversion vs. Calling

Acts’ Narrative

Acts often shows Paul’s transformation as a conversion from Judaism to Christianity, framing it as a dramatic religious shift. This narrative fits the broader theme of Christianity emerging distinct from Judaism (Acts 9:1 – 19). The depiction of Paul’s conversion emphasizes the break between his past as a persecutor of Christians and his new identity as a devoted follower of Christ.

This framing serves to highlight the transformative power of the Christian message and the radical change it brought about in Paul’s life. By presenting his conversion as a decisive break with his past, Acts reinforces the idea of a new and distinct Christian identity. This narrative strategy aligns with the broader theological goals of Acts, which seeks to establish a clear and cohesive account of the spread of Christianity.

Paul’s Letters

Paul’s letters present his transformation as a prophetic calling within his Jewish identity. Paul never describes himself as converting to a new religion but rather as being called to a specific mission to the gentiles. He maintains his identity as a Jew, viewing his apostolic mission as an extension of his Jewish faith (Gal 1:15 – 16 ; Phil 3:5 – 6). Paul’s self-presentation emphasizes continuity rather than rupture, highlighting his ongoing commitment to his Jewish heritage.

This perspective challenges the common view that early Christianity emerged as entirely separate from Judaism. By presenting his mission as a calling within his Jewish identity, Paul underscores the continuity between his past and present, and the broader connections between Judaism and Christianity. This self-understanding reflects the complex and dynamic nature of early Christian identity formation.

B. Implications for Understanding Paul’s Mission

The characterization of Paul’s experience as a calling rather than a conversion underscores the continuity of his Jewish identity. This perspective challenges the common view that early Christianity emerged as entirely separate from Judaism, highlighting instead a complex interplay of identities and missions. By understanding Paul’s mission in this way, we can appreciate the ways in which early Christians navigated their dual identities and the tensions between their Jewish heritage and their new faith.

This understanding also has important implications for interpreting the theological and social dynamics of early Christianity. By emphasizing continuity and integration, we can better understand the diverse and multifaceted nature of early Christian communities and their efforts to negotiate their identities and beliefs. This perspective enriches our understanding of the early church and its complex relationship with Judaism.

IX. Direct Contradictions

A. Early History and Biography

The early history of Paul’s career as a follower of Christ differs significantly between his letters and Acts. Paul admits to being a persecutor of Christians starting in Damascus and only later visiting Jerusalem (Gal 1:17 – 18). Acts, however, describes Paul beginning his persecutory activities in Jerusalem, witnessing Stephen’s stoning, and then traveling to Damascus (Acts 7:58 ; 9:1 – 2). These accounts cannot be harmonized, indicating a fundamental discrepancy.

These differences in early history and biography highlight the distinct narrative and theological goals of the two sources. Paul’s letters emphasize his direct divine calling and his independence from the Jerusalem apostles, while Acts presents a more integrated and collaborative account. These differing portrayals reflect the diverse ways in which early Christians understood and represented their history.

B. Missionary Practices

Acts shows Paul as frequently preaching to Jews first, facing rejection, and then turning to gentiles (Acts 13:5, 13:14 – 46, 18:4 – 6). Paul’s letters, however, depict his mission as primarily to gentiles, with minimal mention of initial efforts among Jews (Gal 2:7 – 9). This difference suggests a divergence in missionary strategy and theological emphasis. Paul’s letters reflect his focus on the gentile mission and his theological arguments for their inclusion in the Christian community.

These differences also highlight the varying theological perspectives within early Christianity. Acts emphasizes the continuity and expansion of the Christian message from Jews to gentiles, while Paul’s letters focus more narrowly on his specific mission and its theological implications. By examining these differing accounts, we can gain a deeper understanding of the diverse and dynamic nature of early Christian theology and practice.

C. Public Speaking and Rhetoric

Acts shows Paul as a skilled speaker, delivering powerful speeches in Greek and Hebrew (Acts 21:40 ; 26:1 – 29). Paul’s letters, in contrast, show him admitting to weak public speaking and physical frailties, offering a more humble self-assessment (2 Cor 10:10). This discrepancy highlights different portrayals of Paul’s public persona. The differing accounts reflect the varied ways in which early Christians constructed and communicated their identities and messages.

The contrasting portrayals also underscore the importance of rhetorical and narrative strategies in shaping early Christian texts. Acts presents a more idealized and cohesive narrative, while Paul’s letters offer a more nuanced and introspective account. By comparing these different images of Paul, we can gain a richer understanding of his life and legacy, and the complex nature of early Christian identity formation.

D. Conversion vs. Calling

Acts frames Paul’s transformation as a conversion from Judaism to Christianity (Acts 9:1 – 19). Paul’s letters describe it as a prophetic calling within his Jewish identity, maintaining continuity with his Jewish faith (Gal 1:15 – 16 ; Phil 3:5 – 6). This difference underscores varying theological narratives. By understanding these differing accounts, we can gain a deeper appreciation for the diverse ways in which early Christians understood their identities and missions.

The differing portrayals also highlight the complex and contested nature of early Christian identity formation. Acts emphasizes the transformative power of the Christian message and the break with the past, while Paul’s letters highlight continuity and integration. By examining these differing perspectives, we can gain a richer understanding of the theological and social dynamics of early Christianity.

X. Conclusion

The contradictions between Paul’s letters and the Acts of the Apostles highlight the complexities of early Christian narratives. These differences reveal the theological and literary reasons behind different portrayals of Paul, highlighting the need for critical evaluation of these sources. By distinguishing between the historical Paul and the Paul of Acts, scholars gain a more nuanced understanding of his life, mission, and theological contributions. This critical approach not only deepens historical knowledge but also enriches our appreciation for the detailed history of early Christian thought and tradition.

These contradictions also underscore the dynamic and contested nature of early Christian identity and theology. By examining these differing accounts, we can gain a deeper understanding of the diverse and multifaceted nature of early Christian communities and the ways in which they constructed and transmitted their histories. This perspective enriches our understanding of the early church and its complex relationship with Judaism and the broader Greco-Roman world.

About Dale B. Martin

Dr. Dale B. Martin was a well-known scholar of the New Testament and early Christianity, serving as the Woolsey Professor of Religious Studies at Yale University until his retirement. Known for his work on social and cultural history in relation to early Christianity, as well as his contributions to biblical interpretation and the historical context of the New Testament texts, Dr. Martin emphasized the importance of understanding the ancient contexts in which these texts were written. His notable works include “The Corinthian Body,” “Sex and the Single Savior,” and “Biblical Truths : The Meaning of Scripture in the Twenty-First Century.” Dr. Martin’s scholarship has profoundly impacted the field of religious studies, influencing both academic and broader understandings of early Christian texts and traditions.