CHAPTER 11

THE QIRA’AAT OF THE QUR’AAN

I. The Meaning of the Word ‘Qira’aat’

The word ‘qir’aat’ is the plural of ‘qiraa’a’, which comes from the root q‑r-a meaning, ‘to read, to recite’. ‘Qiraa’a’ means the recitation of something.

In Qur’aanic sciences, it refers to the various ways and manners of reciting the Qur’aan that are in existence today. As Imaam az-Zarkashee stated, the Qur’aan is the revelation that was given to Muhammad (PBUH), and the qira’aat are the variations in the words and pronunciations of this revelation. Thus the qira’aat are the verbalisation of the Qur’aan, and the Qur’aan is preserved in the qira’aat.

Each qiraa’a has its own peculiar rules of recitation (tajweed) and variations in words and letters, and is names after the reciter (Qaaree) who was famous for that particular qiraa’a.

II. The History of the Qira’aat

The primary method of transmission of the Qur’aan has always been and always will be oral. Each generation of Muslims learns the Qur’aan from the generation before it, and this chain continues backwards until the time of the Companions, who learnt it from the Prophet (PBUH) himself. As ‘Umar ibn al-Khaattaab stated, “The recitation of the Qur’aan is a Sunnah ; the latter generations must take it from the earlier ones. Thereofre, recite the Qur’aan only as you have been taught.” 415 This is the fundamental principal in the preservation of the Qur’aan.

In the last chapter, the revelation of the Qur’aan in the seven ahruf was discussed. As the Prophet (PBUH) recited the Qur’aan in all of these ahruf, the Companions memorised it from him accordingly. Some of them memorised only one harf, others more than this. When the Companions spread throughout the Muslim lands, they took with them the variations that they had learnt from the Prophet (PBUH). They understood the importance of the oral transmission of the Qur’aan. ‘Umar ibn al-Khattaab, during his caliphate, sent several prominent Companions to various cities to teach the people the Qur’aan ; ‘Ubaadah ibn as-Saamit was sent to Hims, Ubay ibn Ka’ab to Palestine, and Aboo ad-Dardaa to Damascus. 416

Likewise, during his caliphate, ‘Uthmaan also realised the importance of the proper recitation of the Qur’aan, and sent reciters of the Qur’aan all over the Muslim lands, each with a copy of his official mus-haf. He kept Zayd ibn Thaabit in Madeenah ; with the Makkan mus-haf, he sent ‘Adullaah ibn Saa’ib (d. 63 A.H.); to Syria was sent al-Mugheerah ibn Shu’bah (d. 50 A.H.); Aboo ‘Abd ar-Rahmaan as-Sulamee (d. 70 A.H.) was sent to Koofah ; and ‘Aamir ibn ‘Abdul Qays to Basrah (d. ~ 55 A.H.). 417

The Companions, in turn, recited and taught these variations to the Successors (Tabi’oon), who taught them to the next generation (atbaa’ at-tabi’oon), and so on. Each generation had in its rank those who were famous for their knowledge of the recitation of the Qur’aan.

Thus, among the Companions, there were many who were famous as having heard from the Prophet (PBUH) most if not all of the Qur’aan. Included in this category are ‘Uthmaan ibn ‘Affaan, ‘Alee ibn Abee Taalib, ‘Ubay ibn Ka’ab, ‘Abdullaah ibn Mas’ood, Zayd ibn Thaabit, Aboo ad-Dardaa, and Aboo Moosaa al-Ash’aree. These Companions taught those Companions who were younger or had not had as much exposure to the Prophet’s (PBUH) recitation, such as Aboo Hurayrah and Ibn ‘Abbaas, who both learnt from Ubay. Some learnt from more than one Companion, as, for example, Ibn ‘Abbaas also learnt from Zayd ibn Thaabit.

These Companions then taught the Successors. Since the Companions spread over the various parts of the Muslim world, each region started developing a specific type of recitation. Again, all of these various recitations had originated from the mouth of the Prophet (PBUH), and the Companions spread the different variations throughout the Muslim world.

Those famous among the Successors for the recitation of the Qur’aan are : in Madeenah, Sa’eed ibn al-Musayyib (d. 90 A.H.), ‘Urwah ibn az-Zubayr (d. 94 A.H.), Saalim (d. 106 A.H.), and ‘Umar ibn ‘Abd al-Azeez (d. 103 A.H.); in Makkah, ‘Ubayd ibn ‘Umayr (d. 72 A.H.), ‘Ataa ibn Abee Rabah (d. 114 A.H.), Taawoos (d. 106 A.H.), Mujaahid (d. 103 A.H.) and ‘Ikrimah (d. 104 A.H.); in Koofah, ‘Alqamah ibn Qays (d. 60 A.H.), Aboo ‘Abd al-Rahmaan as-Sulamee (d. 70 A.H.), Ibraaheem al-Nakhaa’ee (d. 96 A.H.) and ash-Sha’bee (d. 100 A.H.); in Basrah, Aboo al-Aaliyah (d. 90 A.H.), Nasr ibn ‘Aasim (d. 89 A.H.), Qataadah (d. 110 A.H.), Ibn Sireen (d. 110 A.H.) and Yahya ibn Ya’mar (d. 100 A.H.); and in Syria, al-Mugheerah ibn Abee Shihaab and Khaleefah ibn Sa’ad. 418

Around the turn of the first century of the hijrah appeared the scholars of the Qur’aan after whom the qira’aat of today are named. At this time, along with many other sciences of Islaam, the sciences of the qira’aat were codified. Thus, members of this generation took from the Successors the various recitations that they had learnt from the Companions, and adopted a specific way of reciting the Qur’aan, and this is what is called a qiraa’a. Each of these persons is called a Qaaree, or Reciter. These Qaarees were the most famous reciters of the Qur’aan in their time, and people from all around the Muslim lands would come to them to learn the Qur’aan.

To summarise, the qira’aat are particular methodologies of reciting the Qur’aan. They are named after the Qaaree who recited the Qur’aan in that particular manner, and were famous as being the leaders in this field. They represent the various ways that the Companions learnt the Qur’aan from the Prophet (PBUH). They differ from each other in vaious words, proninciations, and rules of recitation (tajweed). They are not the same as the seven ahruf, as shall be elaborated upon shortly.

The scholars of the succeeding generations started compiling works on the different qira’aat that were present in their times. For example, Aboo ‘Ubayd al-Qaasim ibn Sallaam (d. 224 A.H.) compiled twenty-five qira’aat, Ahmad ibn Jubayr al-Koofee (d. 258 A.H.) wrote a book on five qira’aat, and al-Qaadee Ismaa’eel ibn Ishaaq (d. 282 A.H.) compiled his book on twenty qira’aat (including the famous ‘seven’). Even Muhammad ibn Jareer at-Tabari (d. 310) compiled a work on the qira’aat. However, the most famous of these books is the one by Aboo Bakr Ahmad ibn Mujaahid (d. 324), entitled Kitaab al-Qira’aat, in which he compiled seven of the most famous qira’aat of his time from the major cities of the Muslim world. He was the first to limit himself to these particular Qaarees, for he wanted to combine the most famous recitations of Makkah, Madeenah, Koofah, Basrah, and Damascus, for these were the five territories from which the knowledge of Islaam sprung forth — the knowledge of the Qur’aan, tafseer, hadeeth and fiqh. 419 He wrote in his introduction,

“So these seven (that I have chosen) are scholars from Hijaaz (i.e., Makkah and Madeenah), Iraq (i.e., Koofah and Basrah) and Syria (i.e., Damascus). They inherited the Successors in the knowledge of the recitation of the Qur’aan, and the people all accepted and agreed upon their recitation, from their respective territories, and the territories surrounding them…“426

He purposely chose seven Qaarees to match the number of ahruf that the Qur’aan was revealed in. Unfortunately, this led many people to mistakenly believe that the different qira’aat were the same as the ahruf that the Prophet (PBUH) referred to in the various hadeeth. This is obviously false, since ibn Mujaahid wrote his book four centuries after the Prophet’s (PBUH) death. Due to this misconception, many of the later scholars took ibn Mujaahid to task, wishing that he had chosen a different number, so that this confusion could have been prevented. Ibn al-Jazaree (d. 832 A.H.) wrote,

“Many of the scholars disliked the fact that Ibn Mujaahid restricted himself to seven qira’aat, and said that he was mistaken in doing so, and wished that he had chosen a number greater than this, or less than this, or atleast explained the purpose behind choosing this number, so that those people who have no knowledge would not have been misled.” 421

Another misconception that arose was that some scholars assumed that these seven qira’aat were the only authentic qira’aat of the Qur’aan. Thus, these scholars considered any qira’aat besides these seven to be defective (shaadh) qira’aat. This, too, is a misconception, as there were other authentic qira’aat that Ibn Mujaahid did not compile.

Due to the popularity and excellence of Ibn Mujaahid’s book, these seven qira’aat became the most famous qira’aat of that time, 422 and the students of knowledge left other qira’aat to study these seven. Eventually, except for three other authentic qira’aat, all the other qira’aat were left, and only these ten were studied. This does not imply, however, that somehow a portion of the Qur’aan was lost by preserving only these ten. Many of the qira’aat were merely a mixture of others, so that their loss would not mean a loss of certain pronunciations or words. The Muslims are assured of the fact that they have the complete revelation that Allaah revealed to the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), for it is Allaah’s promise to protect it :

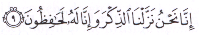

“Verily, it is We who have revealed the Qur’aan, and surely We will guard it” (Qur’?n, 15:9)

III. The Conditions for an Authentic Qiraa’a

It was mentioned in the last section that, during the first few centuries of the hijrah, there were many qira’aat that used to be recited. The scholars of the qira’aat therefore established rules in order to differentiate the authentic qira’aat from the inauthentic ones.

The famous scholar of the Qur’aan, Muhammad ibn al-Jazaree (d. 832 A.H.), said :

“Every qiraa’a that conforms to the rules of Arabic, even if by one manner, and matches with one of the mus-hafs of ‘Uthmaan, even if such a match is not an obvious one, and has an authentic chain of narrators back to the Prophet (PBUH), is an authentic qiraa’a. Such a qiraa’a cannot be refuted or denied, but rather must be believed in, and is amongst the seven ahruf that the Qur’aan was revealed in. Therefore the people must accept it, whether it be from the seven qira’aat (mentioned above), or from the ten qira’aat, or even other than these. And whenever any qiraa’a fails to meet one of the above mentioned three conditions, then it will be labelled (according to which of the conditions are not met) either weak (da’eef), irregular (shaadh), or false (baatil). And this (i.e., these conditions) is the strongest opinion among the scholars of the past and the present.” 423

Therefore, Ibn al-Jazaree mentioned three conditions :

1) The qiraa’a must conform to Arabic grammar. It is not essential, however, that the grammar used be agreed upon by all Arabic grammarians, or that the qiraa’a employ the most fluent and eloquent of phrases and expressions. This is the meaning of the phrase, “…even if by one manner.” The basic requirement is that it does not contradict an agreed upon principal of Arabic grammar.

Some scholars, however, do not agree with this condition.424 They argue, “If a qiraa’a is proven to have originated from the Prophet (PBUH), then we cannot apply the rules of grammar to it. If we were to do this, and presumed an error in the qiraa’a, then we would be implying that the Prophet (PBUH) made mistakes (Allaah forbid!). Therefore, an authentic qiraa’a overrides a rule of Arabic grammar!”

What this is implying is that it is the Qur’aan, through any of its qira’aat , that is given preference over any rule of grammar, for the Qur’aan is the Speech of Allaah, the most eloquent of Speech, and the rules of grammar must be based on this. Among the scholars of the Qur’aan who held this view are Makkee ibn Abee Taalib (d. 437 A.H.) and Aboo ‘Amr ad-Daanee (d. 444 A.H.). For them, the conditions for an authentic qiraa’a are the last two.

Actually, if the practice of the scholars of the Qur’aan is examined, it is apparent that the above difference is a difference in semantics only, for the first category of scholars (such as Ibn al-Jazaree) will reject a rule of grammar as invalid if it contradicts any of the ten authentic qira’aat. Thus, the attempts by some grammarians to invalidate certain qira’aat (such as az-Zajjaaj’s 425 attempts to invalidate the qiraa’a of Hamzah in verse 4:1) have been rejected by all the scholars of qiraa’a, whether they include this condition or not. 426 This point will be discussed in greater detail below.

2) The qiraa’a must conform with one of the mus-hafs of ‘Uthmaan. In the chapter on the compilation of the Qur’aan, it was mentioned that ‘Uthmaan sent out between four and eight mus-hafs around the Muslim world. All of them were without dots and vowel marks. Also, these mus-hafs had minor variations between them.

As long as a qiraa’a satisfied any one of these mus-hafs, it was considered to have passed this condition, even if it conformed slightly. For example, the word maaliki 427 in Soorah al-Faatihah is written in all the ‘Uthmaanic mus-hafs as m‑l-k [Arabic text here], which allows for the variation found in other qira’aat of maliki. 428 This is an example where the conformation is “not obvious.” An example of an explicit conformation is in 2:259, where one recitation is kayfa nunshizuha, 429 but without a dot over one letter becomes kayfa nunshiruha. 430 An example of a qiraa’a conforming to one of the mus-hafs of ‘Uthmaan without the others is the qiraa’a of Ibn ‘Aamir, who read 3:184 as wa bi zuburi wa bil kitaab instead of wa az-zuburi wal kitaab (i.e., without the bas), since the mus-haf that ‘Uthmaan sent to Syria had the two bas in it.

An example of a qiraa’a that contradicts all the mus-hafs of ‘Uthmaan is the qiraa’a attributed to Ibn ‘Abbaas in 18:79, which translates as, “…and there was, behind them, a king who seized every ship by force,” whereas Ibn ‘Abbas read it, “…and there was, in front of them, a king who seized every useable ship by force.” The two changes in the recitation of Ibn ‘Abbaas are not allowed by the mus-haf of ‘Uthmaan, and cannot, therefore, be considered an authentic recitation.

3) The qiraa’a must have an authentic (saheeh) chain of narrators back to the Prophet (PBUH). This is the most important condition, and guarantees that the variations that occur in the qira’aat have all been sent down by Allaah as part of the Qur’aan, recited by the Prophet (PBUH), and passed down to the Muslim ummah without any addition or deletion. As was quoted from ‘Umar earlier (and this same statement has also been made by Zayd ibn Thaabit, and many of the Successors), “The recitation of the Qur’aan is a Sunnah ; the later generations must take it from the earlier ones. Therefore, recite the Qur’aan only as you have been taught.”

However, an important question is : do these chains of narration have to be mutawaatir ? The overwhelming majority of scholars claimed that they did. The only notable exceptions were from Makkee ibn Abee Taalib (d. 437 A.H.), and later Ibn al-Jazaree (d. 832 A.H.) (whose definition is being quoted). Both of these scholars are highly respected, classical scholars in the field of qira’aat.

Ibn al-Jazaree wrote, “Some of the later scholars have presumed… that the Qur’aan can only be proven with mutawaatir narrations ! The flaws in this opinion are obvious… ” 431

However, this opinion itself goes againt the consensus (ijmaa’) of almost all the other scholars. Imaam an-Nuwayree (d. 897 A.H.), a commentator of Ibn al-Jazaree’s work, wrote :

“This opinions is a newly-invented one, contradicting the consensus (ijmaa’) of the jurists and… the four madh-habs… and many scholars, so many that they cannot even be counted, such as Ibn ‘Abd al-Barr, Ibn ‘Atiyyah, Ibn Taymiyyah, Imaam Nawawee, al-Azraa’ee, as-Subkee, az-Zarkashee, Ibn al-Haajib, and many more besides these. As for the reciters of the Qur’aan, they were agreed on this since the earliest times, and the only one to contradict them in the later times are Makkee ibn Abee Taalib 432 and those who followed him (i.e., Ibn al-Jazaree).” 433

In reality, Ibn al-Jazaree’s opinion seems to have more theoretical than realistic value, for even he admits, in another of his works, that the ten qira’aat are all mutawaatir. He states, “Whoever says that the mutawaatir qira’aat are unlimited, then if he means this in our times, this is not correct, for today there are no authentic mutaawatir qira’aat besides these ten ; however, if he means in earlier times, then it is possible that he is correct… ” 434 Therefore, Ibn al-Jazaree was of the view that is was not neccessary for a qiraa’a to be mutawaatir for it to be accepted, but at the same time he did believe that the ten qira’aat were all mutawaatir.

Ibn al-Jazaree’s conditions were perhaps applicable in his time, when there existed numerous qira’aat besides the ten that are present today. According to him, such qira’aat could be recited as long as they had an authentic chain of narrators back to the Prophet (PBUH), even if such chains were ahaad. Most of the other scholars of qiraa’a, however, did not agree with him on this point. 435 However, since in our times, only these ten qira’aat are in existence, this issue becomes more theoretical than practical, as most of the scholars are in agreement that these ten qira’aat are all mutawaatir.

In conclusion, the conditions for an authentic qiraa’a is that it must be mutawaatir, and conforms to atleast one of the mus-hafs of ‘Uthmaan. Any time such a qiraa’a exists, it overides any rule of Arabic grammar.

It should be mentioned, however, that there has never existed any mutawaatir qiraa’a that contradicted any rule of Arabic grammar. 436 Al-Qaarree writes, 437

“If we ponder over this issue, and reflect over these conditions, we finds that this last condition (i.e., the qiraa’a must conform with Arabic grammar) is, in reality, not a ‘condition’ in the sense of the word, meaning that if this ‘condition’ is not met, the qiraa’a is rejected, for two reasons :

Firstly, such a case has never occurred, meaning that there is no authentic, mutawaatir qiraa’a that conforms to the ‘Uthmaanic mus-hafs that has no basis in Arabic grammar.

Secondly, even if we allow for the possiblity that there exists such a qiraa’a — and authentic, mutawaatir qiraa’a conforming to the script, yet not having any basis that we can discover in Arabic grammar — then this too does not imply the rejection of the qiraa’a. This is because our ignorance of such a gramatical basis does not rule out the possibility of such a basis, since no matter how much our knowledge encompasses, it will still be limited. Also, whenever a qiraa’a has a mutawaatir chain of narrators and conforms with the ‘Uthmaanic script, this is unequivocal proof that it is a part of the Qur’aan, and therefore there cannot be any argument against it.

To conclude, therefore, we say : This last condition (meaning the condition of a qiraa’a with Arabic grammar) is in reality a neccessary by product of the other two conditions, and is not a ‘condition’ per se.”

As has already been alluded to, there are ten qira’aat that meet the above requirements, and these will be discussed below, Taqee ad-Deen as-Subkee (d. 756 A.H.) stated,

“The seven qira’aat that ash-Shaatibee compiled 438 along with the other three qira’aat are all authentic mutawaatir qira’aat. This has been recognised by all, and every letter that any of these qira’aat have differed with the others in, is recognised to have been revealed to the Prophet (PBUH). None can reject this fact except the ignorant.” 439

Theoretically, it is possible for there to still exist other authentic qira’aat besides these ten, since there is no divine law regulating that there can only be ten qira’aat. Realistically, however, such an existence is impossible, as the scholars of the Qur’aan would have known of them by now.

IV. The Other Types of Qira’aat

If a qiraa’a fails to meet any of these conditions, it is classified in a different category. Different scholars have adopted different classifications for defining those qira’aat that do not meet the above three conditions. One of the simpler ones is as follows : 440

1) The Saheeh (Authentic) Qira’aat : These are the ten authentic qira’aat, and the conditions of acceptance were discussed above.

2) The Shaadh (Irregular) Qira’aat : These qira’aat have an authentic chain of narration back to the Prophet (PBUH) and conform to Arabic grammar, but do not match the mus-hafs of ‘Uthmaan. In addition, they are not mutawaatir. In other words, they employ words of phrases that the ‘Uthmaanic mus-hafs do not allow. Most of the time (but not all, see Suyootee’s classification below) this type of qira’aat was in fact used by the Companions as explanations to certain verses in the Qur’aan. For example, ‘Aa’ishah used to recite 2:238 ’ …wa salat al-wusta’ with the addition ‘salat al-asr.’ The meaning of the first is, “Guard against your prayers, especially the middle one.” ‘As’ishah’s addition explained that the “middle prayer” alluded to in this verse is in fact the ‘Asr prayer. There are numerous authentic narrations from the Companions of this nature, in which they recited a certain verse in a way that the mus-haf of ‘Uthmaan would not allow.

Another explanation of this type of qira’aat is that they were a part of the ahruf that were revealed to the Prophet (PBUH) but later abrogated, and thus not preserved in the mus-haf of ‘Uthmaan.

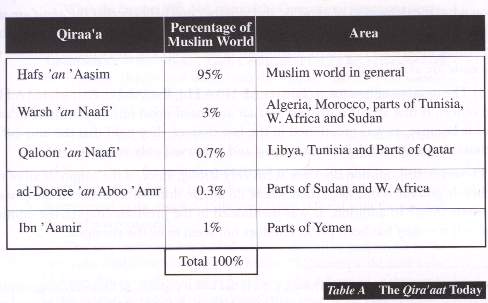

3) The Da’eef (Weak) Qira’aat : These qira’aat conform with Arabic grammar and are allowed by the mus-haf of ‘Uthmaan, but do not have authentic chains of narrations back to the Prophet (PBUH). An example of this type is the recitation of 1:4 as malaki yawmu deen, in the past tense.

4) The Baatil (False) Qira’aat : These qira’aat do not meet any of the three criterion mentioned above, and are rejected completely, even as tafseer. For example, the reading of 35:28 as inama yakhsha Alllaahu min ‘ibadhil ‘ulama, changes the meaning from, “It is only those who have knowledge amongst His slaves that truly fear Allaah,” to, “All?h is afraid of the knowledge of His slaves!” (All praise be to Allaah, He is far removed from all that they ascribe to Him!!)

The ruling concerning these last three types of qira’aat, the shaadh, the da’eef and the baatil, is that they are not a part of the Qur’aan, and in fact it is haraam (forbidden) to consider such a qiraa’a as part of the Qur’aan. If it is recited in prayer, such a prayer will not be acceptable, nor is one allowed to pray behind someone who recites these qira’aat. However, the shaadh and the da’eef qira’aat may be studied under the science of tafseer (and other sciences, such as the science of grammar, or nahw) as long as they are identified as such. The shaadh qira’aat, in particular, used to form a part of the seven ahruf that the Qur’aan was revealed in, but these recitations were abrogated by the Prophet (PBUH) himself, and therefore not preserved by ‘Uthmaan. Under this category fall many of the recitations that are transmitted with authentic chains of narrations from the Companions, and yet do not conform with the ‘Uthmaanic mus-haf. These recitations used to form a part of the Qur’aan, and were recited by the Companions, until they were abrogated by the Prophet (PBUH) before his death.

As-Suyootee, 441 following Ibn al-Jazaree (d. 832), classifies the various qira’aat into six categories, which are briefly :

1) Mutawaatir : These are the seven qira’aat compiled by Ibn Mujaahid, plus the other three.

2) Mash-hoor (Well-known): These are some of the variations found within the ten authentic qira’aat, such as the differences between the raawis and turuqs (to be discussed below).

3) Ahaad (Singular): These are the qira’aat that have an authentic chain of narration, but do not conform to the mus-haf of ‘Uthmaan, or contradict a rule of Arabic grammar (the same as shaadh above).

4) Shaadh (Irregular): These are the qira’aat that do not have an authentic chain of narration back to the Prophet (PBUH) (the same as da’eef above).

5) Mawdoo’ (Fabricated): These are the qira’aat that do not meet any of the three conditions (same as baatil above).

6) Mudraj (Interpolated): In this category, as-Suyootee classified those readings that the Companions used to add of the sake of interpretation. For example, the verse,

“…and he has a brother or sister…” (Qur’?n, 4:12)

was recited by Sa’eed ibn Abee Waqqaas as, “…and he has a brother or sister from the same mother.”

These types of additions are explained as having been heard by that Companion from the Prophet (PBUH), either as an explanation of the verse (in which case it was assumed by the Companion to be part of the verse), or that this was one of the ahruf of that verse that was later abrogated by the Prophet (PBUH) during his final recitation to Jibreel. 442

As-Suyootee stated that the first two types, mutawaatir and mash-hoor, are considered part of the Qur’aan, and can be recited in prayer, but the last four types are not a part of the Qur’aan.

V. The Authentic Qira’aat and the Qaarees

Now that the various types of qira’aat have been discussed in detail, it is time to look at the ten authentic qira’aat, and the Qaarees whom they are named after. 443 The first seven are the ones that Aboo Bakr ibn Mujaahid (d. 324 A.H.) preserved in his book, and which ash-Shaatibee (d. 548 A.H.) versified in his famous poem known as ash-Shaatibiyyah.

1) Naafi’ al-Madanee :

He is Naafi’ ibn ‘Abd al-Rahmaan ibn Abee Na’eem al-Laythee, originally from an Isfahanian family. He was one of the major scholars of qira’aat during his time. He was born around 70 A.H., in Madeenah, and passed away in the same city at the age of 99, in 169 A.H. He learnt the Qur’aan from over seventy Successors, including Aboo Ja’far Yazeed ibn al-Qa’qa’ (d. 130 A.H.), who took his recitation from Aboo Hurayrah, who took his recitation from Ubay ibn Ka’ab, who took his recitation from the Prophet (PBUH). After the era of the Successors, he was taken as the cheif Qaaree of Madeenah. Eventually his qiraa’a was adopted by the people of Madeenah.

Among his students was Imaam Maalik (d. 179 A.H.). Imaam Maalik used to recite the Qur’aan in the qiraa’a of Naafi’, and he used to say, “Indeed, the qiraa’a of Naafi’ is the Sunnah,” 444 meaning that this qiraa’a was the most liked by him.

The two students who preserved his qiraa’a are :

i) Qaloon : He is ‘Eesaa ibn Meena az-Zarqee (120−220 A.H.). He was the stepson of Naafi’, and lived his whole life in Madeenah. After Naafi’ died, he took over his position as the leading Qaaree of Madeenah.

ii) Warsh : He is Aboo Sa’eed ‘Uthmaan ibn Sa’eed al-Misree (110−197 A.H.). He lived in Egypt, but travelled to Madeenah in 155 A.H. to study under Naafi’, and recited the Qur’aan to him many times. Eventually, he returned to Egypt, and became the leading Qaaree of Egypt.

2) Ibn Katheer al-Makkee :

He is ‘Abd Allaah ibn Katheer ibn ‘Umar al-Makkee, born in Makkah in 45 A.H. and died 120 A.H. He was among the generation of the Successors (he met some Companions, such as Anas ibn Maalik and ‘Abdullaah ibn az-Zubayr), and learnt the Qur’aan from the early Successors, such as Abee Saa’ib, Mujaahid ibn Jabr (d. 103 A.H.), and Darbaas, the slave of Ibn ‘Abbaas. Darbaas learnt the Qur’aan from Ibn ‘Abbaas, who learnt it from Zayd ibn Thaabit and Ubay ibn Ka’ab, who both learnt it from the Prophet (PBUH).

Imaam ash-Shaafi’ee (d. 204 A.H.) used to recite the qiraa’a of Ibn Katheer, 445 and once remarked, “We were taught the qiraa’a of Ibn Katheer, and we found the people of Makkah upon his qiraa’a.” 446

The two primary Qaarees who preserved his qiraa’a are :

i) al-Buzzee : He is Abul Hasan Ahmad ibn Buzzah al-Makkee (170−250 A.H.). He was the mu’adh-dhin at the Masjid al-Haraam at Makkah, and the leading Qaaree of Makkah during his time.

ii) Qumbul : He is Aboo ‘Amr Muhammad ibn ‘Abd al-Rahmaan (195−291 A.H.). He was the leading Qaaree of the Hijaaz. He was also one of the teachers of Aboo Bakr ibn Mujaahid (d. 324 A.H.), the author of Kitaab al-Qira’aat.

3) Aboo ‘Amr al-Basree :

He is Zabaan ibn al-‘Alaa ibn ‘Ammaar al-Basree. He was born in 69 A.H. and passed away in 154 A.H. He was born in Makkah, but grew up in Basrah. He studied the Qur’aan under many of the Successors, among them Aboo Ja’far (d. 130 A.H.), and Aboo al-‘Aaliyah (d. 95 A.H.), who learnt from ‘Umar ibn al-Khattaab and other Companions, who learnt from the Prophet (PBUH).

The two primary Qaarees who preserved his qiraa’a are :

i) ad-Doori : He is Hafs ibn ‘Umar ad-Doori (195−246 A.H.). He was one of the first to compile different qira’aat , notwithstanding the fact that he was blind.

ii) as-Soosee : He is Aboo Shu’ayb Saalih ibn Ziyaad as-Soosee (171−261 A.H.). he taught the Qur’aan to Imaam an-Nasaa’ee (d. 303 A.H.), of Sunan fame.

4) Ibn ‘Aamir ash-Shaamee :

He is ‘Abdullaah ibn ‘Aamir al-Yahsabee, born in 21 A.H. He lived his life in Damascus, which was the capital of the Muslim empire in those days. He met some of the Companions, and studied the Qur’aan under the Companion Aboo ad-Dardaa, and al-Mugheerah ibn Abee Shihaab. He was the Imaam of the Ummayad Mosque (the primary mosque in Damascus) during the time of ‘Umar ibn ‘Abd al-‘Azeez (d. 103 A.H.), and was well-known for his recitation. Among the seven Qaarees, he has the highest chain or narrators (i.e., least number of people between him and the Prophet (PBUH)), since he studied directly under a Companion. He was also Chief Judge of Damascus. His qiraa’a became accepted by the people of Syria, He died on the day of ‘Aashoora, 447 118 A.H.

The two primary Qaarees who preserved his qiraa’a are :

i) Hishaam : He is Hishaam ibn ‘Ammaar as-Damishqee (153−245 A.H.). He was well-known for his recitation, and his knowledge of hadeeth and fiqh, and was one of the teachers of Imaam at-Tirmidhee (d. 279 A.H.).

ii) Ibn Zhakwan : He is ‘Abdullaah ibn Ahmad ibn Zhakwan (173−242 A.H.). He was also the Imaam of the Ummayad Mosque during his time.

5) ‘Aasim al-Koofee :

He is ‘Aasim ibn Abee Najood al-Koofee, from among the Successors. He was the most knowledgable person in recitation during his time, and took over the position of Imaam of the Qaarees in Koofah, after the death of Aboo ‘Abd ar-Rahmaan as-Sulamee (d. 75 A.H.). He learnt the Qur’aan from Aboo ‘Abd ar-Rahmaan (who studied under ‘Alee ibn Abee Taalib, and was the teacher of al-Hasan and al-Husayn), and from Zirr ibn Hubaysh (d. 83 A.H.) and Aboo ’ Amr ash-Shaybaanee (d. 95 A.H.). These learnt the Qur’aan from Ubay ibn Ka’ab, ‘Uthmaan ibn ‘Affaan, ‘Alee ibn Abee Taalib, and Zayd ibn Thaabit, who all learnt from the Prophet (PBUH). He passed away 127 A.H.

He taught the Qur’aan to Imaam Aboo Haneefah (d. 150 A.H.), who used to recite in the qiraa’a of ‘Aasim. Imaam Ahmad ibn Hambal (d. 204 A.H.) was once asked, “Which of the qira’aat do you prefer?” He replied, “The qiraa’a of Madeenah (i.e., Naafi’), but if this is not possible, then ‘Aasim.” 448

His two students who preserved his qiraa’a are :

i) Shu’ba : He is Shu’ba ibn ‘Iyaash al-Koofee, born 95 A.H. and passed away 193 A.H.

ii) Hafs : He is Aboo ‘Amr Hafs ibn Sulaymaan al-Asadee al-Koofee (90−180 A.H.), a step-son of ‘Aasim. He was the most knowledgable person of the qiraa’a of ‘Aasim.

6) Hamzah al-Koofee :

He is Hamzah ibn Habeeb al-Koofee, born 80 A.H. He met some of the Companions, and learnt the Qur’aan from al-Amash (d. 147 A.H.), Ja’far as-Saadiq (d. 148 A.H.) (the great-grandson of Husayn), and others. His qiraa’a goes back to the Prophet (PBUH) through ‘Alee ibn Abee Taalib and ‘Abdullaah ibn Mas’ood. he passed away 156 A.H.

The two primary Qaarees through whom his qiraa’a is preserved are :

i) Khalaf : He is Khalaf ibn Hishaam al-Baghdaadee (150−227 A.H.). He memorised the Qur’aan when he was ten years old.

He also has his own qiraa’a, different from the one he preserved from Hamzah (see below).

ii) Khallaad : He is Aboo ‘Eesaa Khallaad ibn Khaalid ash-Shaybaanee. he was born 119 A.H. and passed away 220 A.H.

7) Al-Kisaa’ee

He is Alee ibn Hamzah ibn ‘Abdillaah, born around 120 A.H. He was the most knowledgable of his contemporaries in Arabic Grammar, and is considered one of the classical scholars in this field. He authored numerous books, and excelled in the sciences and recitation of the Qur’aan. Students used to flock to him to listen to the entire Qur’aan, and they even used to record where he stopped and started every verse. The Caliph Haroon ar-Rasheed used to hold him in great esteem. He passed away 189 A.H.

His two primary students who preserved his qiraa’a are :

i) al-Layth : he is al0Layth ibn Khaalid al-Baghdaadee. He died 240 A.H.

ii) ad-Dooree : He is the same ad-Dooree who is the student of Aboo ‘Amr al-Basree (mentioned above), for he studied and preserved both of these qira’aat.

These are the seven Qaarees whom Ibn Mujaahid compiled in his book Kitaab al-Qira’aat. Of these, all are from non-Arab backgrounds except Ibn ‘Aamir and Aboo ‘Amr. The following three Qaarees complete the ten authentic qira’aat.

8) Aboo Ja’far al-Madanee :

He is Yazeed ibn al-Qa’qa’ al-Makhzoomee, among the Successors. He is one of the teachers of Imaam Naafi’, and learnt the Qur’aan from ‘Abdullaah ibn ‘Abbaas, Aboo Hurayrah and others. he passed away in 130 A.H.

His two primary students who preserved his qiraa’a were ‘Eesaa ibn Wardaan (d. 160 A.H.) and Sulaymaan ibn Jamaz (d. 170 A.H.)

9) Ya’qoob al-Basree :

He is Ya’qoob ibn Ishaaq al-Hadhramee al-Basree. He became the Imaam of the Qaarees in Basrah after the death of Aboo ‘Amr ibn ‘Alaa. he studied under Aboo al-Mundhir Salaam ibn Sulaymaan. His qiraa’a goes back to the Prophet (PBUH) through Aboo Moosaa al-Ash’aree. He was initially considered among the seven major Qaarees by many of the early scholars, but Ibn Mujaahid gave his position to al-Kisaa’ee instead. He passed away in 205 A.H.

His two primary students were Ruways (Muhammad ibn Muttawakil, d. 238 A.H.) and Rooh (Rooh ibn ‘Abd al-Mu’min al-Basree, d. 235 A.H.), who was one of the teachers of Imaam al-Bukhaaree (d. 256 A.H.).

10) Khalaf :

This is the same Khalaf that is one of the two students of Hamzah. He adopted a specific qiraa’a of his own, and is usually called Khalaf al-‘Aashir (the ‘tenth’ Khalf).

His two primary students who preserved this qiraa’a were Ishaaq (Ishaaq ibn Ibraaheem ibn ‘Uthmaan, d. 286 A.H.) and Idrees (Idrees ibn ‘Abd al-Kareem al-Baghdaadee, d. 292 A.H.)

All of these ten qira’aat have authentic, mutawaatir chains of narration back to the Prophet (PBUH). Each qiraa’a is preserved through two students of the Imaam of that qiraa’a. Of course, these Qaarees had more than just two students ; the reason that the qira’aat are preserved through only two is that Aboo ‘Amr ‘Uthmaan ibn Sa’eed (d. 444), better known as Imaam ad-Daanee, selected and preserved the recitation of the two best students of each Qaaree in his book, Kitaab at-Tayseer fee al-Qira’aat as-Saba’. These two students are each called Raawis (narrators), and they occasionally differ from each other. Thus, although other Raawis also narrated each qiraa’a, only the recitation of two main Raawis have been preserved in such detail. References to the recitation of other Raawis are, however, to be found in the classical works of qira’aat.

These Raawis learnt the qiraa’a from their Imaam, and each preserved some of the variations of the recitation of the Qaaree. Sometimes, the Qaaree taught different qira’aat to each Raawi. Hafs quoted ‘Aasim as saying that the qiraa’a he taught him was that of Aboo ‘Abd al-Rahmaan as-Sulamee (d. 70 A.H.) from ‘Alee ibn Abee Taalib, while the one that he taught Aboo Bakr ibn ‘Iyaash (i.e., Shu’ba, the other Raawi of ‘Aasim) was that of Zirr ibn Hubaysh (d. 83 A.H.) from Ibn Mas’ood. 449

However, typically the variations between the Raawis are minor when compared to the differences between the qira’aat themselves (although usually there are differences in the rules of tajweed of the Raawis). For example, Shu’ba and Hafs differ from each other in around forty places in the whole Qur’aan. 450 To preserve even these differences, however, the qira’aat are always mentioned including the Raawis. So, when someone recites the qira’aat of Naafi’, for example, he should mention whether it is through Warsh or Qaloon (for example, by saying, “The qira’aat of Naafi’ through the riwaayah of Warsh,” or, “The qiraa’a of Warsh ‘an Naafi’ ” for short). 451

Most of the time, these students, who were Qaarees in their own right, studied directly under the Qaaree whose qiraa’a it was. Thus, for example, Warsh and Qaloon both studied under Imaam Naafi’, as did Shu’bah and Hafs with Imaam ‘Aasim. However, sometimes, there was an intermediary (or even two) between these students and the Imaam. When this occured, as for example with Ibn Katheer, the intermediary was not mentioned above, so as not to prolong the discussion. The interested reader may consult any of the references mentioned in the beginning of this section.

There are four shaadh qira’aat (following the original defination above). These are not considered as part of the Qur’aan, but maybe used as tafseer, and, according to some of the madh-habs, as a basis for fiqh rulings as well. 452 The Qaarees whom they are named after are :

1) al-Hasan al-Basree : This is the famous Successor, Hasan ibn Abee al-Hasan Yassaar Aboo Sa’eed al-Basree. He passed away 110 A.H.

2) Ibn Muhaysin : He is Muhammad ibn ‘Abd al-Rahmaan as-Suhaymee al-Makkee. He was one of the Chief Qaarees of Makkah, along with Ibn Katheer. He passed away 123 A.H.

3) Yahya al-Yazeedee : He is Yahya ibn al-Mubaarak ibn al-Mugheerah. He passed away 202 A.H.

4) al-Shamboozee : He is Muhammad ibn Ahmad ibn Ibraaheem al-Shamboozee. He passed away 388 A.H.

These four qira’aat contain most of the qira’aat that were recited by the Companions and did not conform to the mus-haf of ‘Uthmaan. Of course, these four qira’aat did not contradict the mus-haf of ‘Uthmaan in every single verse ; only occasionally is there a conflict.

VI. The Qira’at Today

The qira’aat were once a vital part of the Muslim ummah, and each part of the Muslim world used to recite according to one of the qira’aat. Not surprisingly, the people of a particular city would recite in the qiraa’a of the Qaaree of that city. Thus, for example, Makkee ibn Abee Taalib (d. 437 A.H.) reported, in the third century of the hijrah, that the people of Basra followed the recitation of Aboo ‘Amr, those of Koofah followed ‘Aasim, the Syrians followed Ibn ‘Aamir, Makkah took after Ibn Katheer, and Madeenah followed Naafi’.

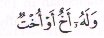

Eventually, however, most of the other qira’aat died out and were replaced by other ones. Thus, the situation today is that the vast majority of the Muslim world recites only the qiraa’a of ‘Aasim through the riwaya of Hafs (Hafs ‘an ‘Aasim). However, there are certain areas in the world where other qira’aat are prevalent, and a rough breakdown is as follows :

This is obviously a rough very breakdown, based on the population in these respective countries. 453

The qira’aat today are as a whole only memorisedin specialised institutions of higher learning throughout the Muslim world (or, a student may study privately under a scholar who has memorised these qira’aat). A student of the Qur’aan who wishes to memorise the qira’aat must, of course, have already memorised the entire Qur’aan in atleast one qiraa’a. There are two primary ways of memorising these qira’aat, and both involve memorising lengthy poems that detail the rules of recitation (tajweed) of each qiraa’a, and the differences between them.

The first way is to memorise the Shaatibiyyah (its actual name is Hirz al-Amaanee wa Wajh at-Tahaanee), which is a poem consisting of 1173 couplets, written by Imaam Qaasim ibn Ahmad ash-Shaatibee (d. 548 A.H.), and then to memorise the Durrah (short for ad-Durrah al-Madhiyyah) by Muhammad Ibn al-Jazaree (d. 832 A.H.). The first poem deals with the first seven qira’aat. After a student of the Qur’aan has memorised this, he then moves on to the second poem, which deals with the last three qira’aat. This is the primary method by which the qira’aat are taught throughout the Muslim world.

The second method is to learn all ten qira’aat simultaneously, by memorising the Tayyibah (short for Tayyibah an-Nashr fil Qira’aat al-‘Ashr), which is a poem that deals with all ten qira’aat , also by Muhammad ibn al-Jazaree. 454

VII. The Relationship of the Ahruf with the Qira’aat

The relationship of the ahruf with the authentic qira’aat must by essence depend upon what the definition of ahruf is, and whether one believes that the ahruf are still in existence today. Therefore, the scholars of Islaam have defined this relationship depending upon their respective definitions of the ahruf. The three major opinions on this issue are as follows : 455

1) The opinion of Imaam at-Tabaree (d. 310 A.H.), Ibn ‘Abd al-Barr (d. 463 A.H.), and others, is that all the authentic qira’aat are based upon one harf of the Qur’aan. This is because, as was mentioned in the last chapter, they hold that the mus-haf of ‘Uthmaan eliminated the other six ahruf and preserved only one harf.

However, this opinion does not seem very strong, since, if the origin of all of the authentic qira’aat is one harf, then where do all the differences between the qira’aat originate from ? In addition, as was mentioned in the previous chapter, the opinion that only one harf has been preserved does not seem to be the strongest.

2) The opinion of al-Baaqillaani (d. 403 A.H.) and a few scholars is that all of the seven ahruf are preserved in the qira’aat, such that each harf is found scattered throughout the qira’aat. Therefore, there is no single qira’aat that corresponds exactly to any one harf, but each qiraa’a represents various ahruf such that, in the sum total of the qira’aat, the ahruf are preserved.

This opinion also is based upon these scholars’ belief that all of the ahruf have been preserved. This opinion seems like a strong opinion, except for the fact that there exists many narrations in which the Companions used to recite differently from any of the present qira’aat (these are today present in the shaadh qira’aat). It seems that they were reciting a peculiar harf of the Qur’aan, but this was not preserved in the qira’aat. 456

3) The opinion of Makkee ibn Abee Taalib (d. 437 A.H.), Ibn al-Jazaree (d. 832 A.H.), Ibn Hajr (d. 852 A.H.), as-Suyootee, and others, and the one that is perhaps the strongest, is that the qira’aat represent portions of the seven ahruf, but not all of the seven ahruf in totality. The differences between the qira’aat, even the most minute of differences, originate from the seven ahruf, but not every difference between the seven ahruf is preserved in the qira’aat. This goes back to our position on the existence of the ahruf today : that they exist inasmuch as the script of the mus-haf of ‘Uthmaan allows them to. In the last chapter, the methodology that the Companions used to decide which ahruf to preserve was discussed. Those ahruf that were preserved are the ones that are in existence today, through the variations in the qira’aat.

To summarise the last two chapters, we quote Makkee ibn Abee Taalib (d. 437 A.H.), who wrote,

“When the Prophet (PBUH) died, many of the Companions went to the newly conquered territories of the Muslims, and this was during the time of Aboo Bakr and ‘Umar. They taught them the recitation of the Qur’aan and the fundamentals of the religion. Each Companions taught his particular area the recitation that he had learnt from the Prophet (PBUH) (i.e., the various ahruf). Therefore the recitations of these territories differed based on the differences of the Companions.

Now, when ‘Uthmaan ordered the writing of the mus-hafs, and sent them to the new provinces, and ordered them to follow it and discard all other readings, each of the territories continued to recite the Qur’aan the same way that they had done so before the mus-haf had reached them, as long as it conformed to the mus-haf. If their recitation differed with the mus-haf, they left that recitation…

This new recitation was passed on from the earlier generations to the later ones, until it reached these seven Imaams 457 (Qaarees) in the same form, and they differed with each other based upon the differences of the people of the territories — none of whom differed with the mus-haf that ‘Uthmaan had sent to them. This, therefore, is the reason that the Qaarees have differed with each other…” 458

Therefore, the differences in the qira’aat are ramnants of the differences in the way that the Prophet (PBUH) taught the recitation of the Qur’aan to the different Companions, and these differences were among the seven ahruf of the Qur’aan which Allaah reevaled to the Prophet (PBUH). Thus, the ten authentic qira’aat preserve the final recitation that the Prophet (PBUH) recited to Jibreel — in other words, the qira’aat are manifestations of the remaining ahruf of the Qur’aan.

VIII. The Benefits of the Qira’aat

Since the qira’aat are based on the ahruf, many of the benefits of the qira’aat overlap with those of the ahruf. Some of the benefits are as follows.

1) The facilitation of the memorisation of the Qur’aan. This includes not only differences in pronunciations that the different Arab tribes were used to, but also the differences in words and letters.

2) Proof that the Qur’aan is a revelation from Allaah, for notwithstanding the thousands of differences between the qira’aat, not a single difference is contradictory.

3) Proof that the Qur’aan has been preserved exactly, as all of these qira’aat have been recited with a direct, authentic, mutawaatir chain of narrators back to the Prophet (PBUH).

4) A further indication of the miraculous nature (‘ijaaz) of the Qur’aan, because these qira’aat add to the meaning and beauty of the Qur’aan in a complementary manner, as shall be shown in the next section.

5) The removal of any stagnation that might exist with regards to the text of the Qur’aan. In other words, there exist various ways and methodologies of recitaing the Qur’aan that are different from each other in pronunciation and meaning, and thus the text remains vibrant and never becomes monotonous. 459

IX. Some Examples of the Different Qira’aat

It is appropriate to conclude this chapter by quoting various verses that demonstrate some of the differences in the qira’aat, with a discussion of the various meanings. 460 Four verses were chosen, the first of which deals belief, the second and third with stories, and the last with laws. In each verse, it will be seen that, far fromcontradicting each other, the qira’aat taken together add much deeper meanings and connotations than any one of them individually. In fact, the various readings between the qira’aat are considered — in terms of extracting rulings from verses — as two seperate verses, both of which must be looked into, and neither of which can abrogate the other.

The scholars of this century, Muhammad Ameen ash-Shanqeetee (d. 1393 A.H.), said in his famous tafseer, Adwaa al-Bayaan, “In the event that the different qira’aat seem to give contradictory rulings, they are considered as different verses…” 461 meaning that both of them must be taken into account for the final ruling to be given. This same principal applies in verses that deal with stories or belief, as the example below will show.

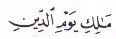

1) Soorah Faatihah, verse 4.

The first reading, that of ‘Aasim and al-Kisaa’ee, is maaliki yawm ad-deen. This is the recitation that most of the readers will be familiar with. The word maalik means ‘master, owner,’ and is one of the Names of Allaah. The emaning of this name when attributed to Allaah is that Allaah is the one who Possesses and Owns all of the Creation, and therefore He has full right to do as He pleases with His creation, and He has the power to do what He pleases with His creation, and no one can stop or question Him.

The verse therefore translates, “The Only Owner of the Day of Judgement.” This name (maalik) is also mentioned in,

“Say : O Allaah ! Maalik (Possessor) of (all) Kingdoms!” (Qur’?n, 3:26)

Allaah is the Owner who Possesses all things, and on the Day of Judgement, He will Own Rulership and Kingship. As Allaah says,

“The sovereignty on that day (i.e., the Day of Judgement) will be the true (sovereignty), belonging to the Most Beneficent” (Qur’?n, 25:26)

If Allaah is the only Maalik on the Day of Judgement, this automatically implies that He is the Maalik before the Day of Judgement also, since the one who is the Maalik on that day must be the Maalik of all that was before that Day !

The second reading, that of Naafi’, Aboo ‘Amr, Ibn ‘Aamar, Ibn Katheer and Hamzah, is maliki yawm ad-deed, without the alif. The word ‘malik’ means, “king, sovereign, monarch,” and is also one of the Names of Allaah. This also has the connotation of the one who has power to judge. A king (Malik) possesses not only wealth and property (like a Maalik), but also the authority to rule, judge and command. The verse therefore translates, “The King (and the Only Ruling Judge) of the Day of Judgement.” Malik, as one of the names of Allaah, is mentioned in the Qur’aan :

“…the King…” (Qur’an, 59:23)

and also

“The King of men” (Qur’an, 114:2)

The name of All?h ‘Malik’ is a description of Allaah (i.e., sifah dhaatiyyah), since He is ‘The King’; whereas the name ‘Maalik’ is a description of Allaah and His actions (i.e., sifah fi’liyyah), since He is ‘The Owner’ of all of His creation. 462

It can be seen that the two readings increase the overall meaning of the verse, each giving a connotation not given by the other, and thus increasing the beauty and eloquence of the verse.

“The result of the two qiraa’a is that Allaah is the Maalik on the Day of Judgement, and the Malik. So on that Day, He will be the Owner (Maalik) of the Day of Judgement — no other person will be an owner besides Him in Judgement, even though they might have been owners of judgement in this world. And Allaah is the King (Malik) of the Day of Judgement, besides all else of His creation, who, in this world, were mighty and arrogant kings…so on this day, these (kings) will know for sure that they are in reality the most humiliated of creation, and that the true Might, and Power, and Glory and Kingship belongs only to Allaah, as Allaah, all Glory and Praise be to Him, has said,

“The Day when they will (all) come out, nothing of them will be hidden from Allaah. Whose is the Kingdom on this day?! (Allaah Himself will reply:) It is Allah’s, the Unique, the Irresistible” (Qur’?n, 40:16)

So, Allqh has informed us that He is the Malik of the Day of Judgement, meaning that He is the only one whom Kingship belongs to, besides all the kings and rulers of this world, and on this day these kings and rulers will be in the greatest humiliation and disgrace, instead of their (wordly) power and glory…

And Allqh has informed us that He is the Maalik of the Day of Judgement, meaning that He is the only one whom Ownership belongs to. So, there is none that can pass judgements or rule on that Day except Him.” 463

2) Soorah al-Baqarah, verse 259.

This verse tells the story of a man who passed by a deserted town, and wondered how All?h would ever bring it back to life. Thus, as a miracle for him, Allaah caused him to die for a hundred years, then brought him back to life. Allaah also brought the man’s donkey back to life in front of his eyes.

The first reading of the relevant part of the verse, by al-Kisaa’ee, Ibn ‘Aamir, ‘Aasim and Hamzah, is, “kayfa nunshizuha”. This is in reference to the resurrection of the donkey. The word nunshizuha means, “to cause to rise.” The verse therefore translates , “Look at the bones (of the Donkey), how We raise them up,” meaning, “…how We cause the bones to join one another and stand up again (from the dust).”

The second reading, by Aboo’ Amr, Naafi’ and Ibn Katheer, is, “kayfa nunshiruha”. The word nunshiruha means, “to bring to life, to resurrect.” The verse then translates, “…how We resurrect it and bring it back to life.”

Again, both readings give different meanings, but put together these readings help form a more complete picture. The bones of the donkey were ‘raised up’ from the dust and ‘resurrected’ (meaning clothed with flesh) in front of the man. Each reading gives only a part of the picture, but put together, a more graphic picture is given.

3) In the last portion of the same verse, the readings differ as follows :

The first reading, that of Naafi’, Ibn Katheer, ‘Aasim, Ibn ‘Aamir and Aboo Amr, is “Qaalaa a’lamu ana Allaaha ‘alaa kulli shayin qadeer”. This translates as, “He said, ‘I (now) know that Allaah is indeed capable of all things.’ ” This shows that, after this miraculous display, the man finally believed that All?h could bring the dead back to life, and repented from his previous statement.

The second reading, that of Hamzah and al-Kisaa’ee, is, “Qala ‘lam ana Allaaha…” which translates as, “It was said (to him): ‘Know that Allaah is capable of all things.’ ” In this reading, after the resurrection of the donkey was shown to him, he was ordered to believe that Allaah was indeed All-Powerful.

Once again, each reading adds more meaning to the overall picture. After this miraculous display, the man was commanded to know that Allaah is indeed capable of all things. He responded to this command, and testified that, indeed, Allaah is capable of all things. 464

4) Soorah al-Maaidah, verse 6.

For the last example, it will be seen that even different fiqh ruling are given by the differences in the qira’aat.

The relevant verse discusses the procedure for ablution (wudoo). In the reading of Naafi’, Ibn ‘Aamir, al-Kisaa’ee and Hafs, the verse reads as follows : “O you who believe ! When you intend to pray, wash your faces and your hands up to the elbows, wipe your heads, and (wash) your feet up to the ankles…” The word ‘feet’ is read arjulakum, and in this tense, it refers back to the verb ‘wash.’ Therefore, the actual washing of the feet is commanded, according to this recitation.

The remaining qira’aat pronounce the word arjulikum, in which case it refers back to the verb ‘wipe,’ so the verse would read, “…wash your faces and hands up to the elbows, and wipe your hands and feet…” According to this recitation, washing is not obligatory, and wiping is sufficient.

This is an apparent contradiction between the qira’aat. Does one ‘wipe’ his feet (meaning pass water over it, similar to how the head is wiped in ablution), or does one actually wash his feet (like the hands and face are washed)? In fact, there is no contradiction whatsoever, for each recitation applies to a different circumstance. In general, the ablution is performed by ‘washing’ the feet. However, if a person is wearing shoes or socks, and he had ablution before putting them on, he is allowed — in fact even encouraged — to ‘wipe’ over his feet, and is not obliged to wash them. 465 Az-Zarkashee said, “These two verses can be combined to understand that one reading deals with wiping over the socks, while the second reading deals with washing the feet (in case of not wearing socks).” 466

Therefore, each of these recitations adds a very essential ruling concerning the ablution, and there is no contradiction between them.

It can be seen from this section that the qira’aat are a part of the eloquence of the Qur’aan, and form an integral factor in the miraculous nature of the Qur’aan. For indeed, what other book in human history can claim the vitality that is displayed in the qira’aat — the subtle vatiations in letters and words that change and complement the meaning of the verse, not only in story-telling but also in beliefs and commands and prohibitions ! To add to this miracle, all of these changes originate from the one script of ‘Uthmaan ! Indeed, there can be no doubt the Qur’aan is the ultimate miracle of the Prophet (PBUH).

Notes and References

415 Itr, p. 244

416 Wohaibee, p. 46

417 az-Zarqaanee, v.1, p. 404.

418 It should be kept in mind that this is a partial list and is far from exhaustive. Those who are interested may consult Ubaydaat, p. 164, Qattaan, p. 170, and az-Zarqaanee, v.1, pps. 414 – 416.

419 Uwais, p. 16.

420 Ibn Mujaahid, p. 87.

421 Ibn al-Jazaree, p. 39.

422 This is very similar to what happened in the history of hadeeth. The reason that six particular books of hadeeth (a‑Bukhaaree, Muslim, Aboo Daawood, at-Tirmidhee, an-Nasaa’ee and Ibn Maajah) are known as the “Sihaah Sitta” or the “Six Authentic Books”, is because of one book on the ‘Names of Narrators’, Asmaa ar-Rijaal, written by ‘Abd al-Ghanee al-Maqdisee (d. 600 A.H.). Due to the throughness of this work, people started classifying these six books separately from other works of hadeeth, and many considered these six books as authentic (saheeh). This description, however, is only applicable on the two saheeh collection of al-Bukhaaree and Muslim ; the rest of these works contain both authentic and inauthentic ahaadeeth.

423 Ibn al-Jazaree, p. 9. I have paraphrased from the Arabic.

424 cf. az-Zarqaanee, v.1, p. 422.

425 He is ‘Abd al-Rahmaan ibn Ishaaq az-Zujjaaj al-Nihawandee (d. 332), a noted Muslim grammarian.

426 az-Zarkashee, Bahr, v.1, p. 471.

427 The qiraa’a of ‘Aasim and al-Kisaa’ee

428 The qiraa’a of Warsh, Ibn Katheer, Ibn ‘Aamir, Hamzah and Aboo ‘Amr.

429 The qiraa’a of ‘Aasim, and others

430 The qiraa’a of Naafi’, and others

431 Ibn al-Jazaree, p. 13.

432 Makkee ibn Abee Taalib is quoted as having been the first to hold this opinion in all the works that I have come across discussing this topic (also see, al-Qadhi, p. 8). However, I came across another work of his entitled Kitaab al-Ibaanah ‘an Ma’aani al-Qira’aat, in which he clearly states that any qiraa’a must be mutawaatir for it to be accepted. For example, on p. 43, while discussing the shaadh qira’aat, he states, “…and the Qur’aan cannot be confirmed with an ahaad narration;” on p. 31, “…and this (i.e., taking a shaadh qira’aat) implies confirming the Qur’aan with an ahaad narration, and this is not allowed by any of the people (of knowledge).” Elsewhere (p. 39), he clearly states concerning this opinion “…and this is the opinion we believe and hold to.” I did not see any of the other books that I read mention these quotes, so I do not know whether this was his earlier opinion, or his later one, nor could I ascertain when he wrote the book. In any case, further research must be done to ascertain whether this really was the final opinion of Makkee ibn Abee Taalib.

433 al-Qadhi, p.8.

434 Uwais, p. 12, quoting from Ibn al-Jazaree’s Munjid al-Muqreen. Also, see Uwais’ discussion on this point, pps. 11 – 14.

435 Other scholars make a differentiation between the Qur’aan and the qira’aat, and state that, in order for the Qur’aan to be accepted, the narrations must be mutawaatir, but in order for a qiraa’a to be accepted, an ahaad narration will suffice. However, this differentiation does not seem to solve the problem, for the qira’aat are the Qur’aan, and the Qur’aan is preserved in all of the qira’aat. Therefore, if a qiraa’a is substantiated as authentic, that automatically implies that it is part of the Qur’aan.

436 This is not to say that there have not existed qira’aat that Arab grammarians have not found fault with. There have been numerous attempts to prove various grammatical ‘faults’ in the qira’aat, but other grammarians have always proven that such readings do have grammatical basis for them. cf. al-Qaaree, Abd al-Aziz : Hadith al-Ahruf as-Saba’ah, in Majalah Kulliyah al-Qur’aan al-Kareem, v. 1, 1983, p. 115, for examples.

437 al-Qaaree, p. 116, with paraphrasing. The addition in brackets are mine.

438 Qaasim ibn Ahmad as-Shaatibee (d. 590 A.H.) compiled the seven qira’aat of Aboo Bakr ibn Mujaahid in a poem known as the Shaatibiyah to facilitate its memorisation.

439 as-Suyootee, v.1, p.82

440 Ubaydaat, p. 178

441 as-Suyootee, v.1, p. 102

442 cf. as-Suyootee, v.1, p. 102

443 All of the biographical information in this section, unless otherwise referenced, was taken from al-Banna v.1, pps. 19 – 32, az-Zarqaanee, v.1, pps 456 – 477, and al-Haashimee, pps. 39 – 155.

444 al-Haashimee, p. 39

445 Hence his opinion of the origin of the word ‘Qur’aan’; cf, Ch.2, ‘The meaning of the word ‘qur’aan’.

446 al-Haashimee, p. 59

447 The tenth of Muharram

448 al-Haashimee, p. 116

449 Wohaibee, p. 106

450 Meaning that they differ from each other in forty words, but since these words occur a total of around five hundred times in the Qur’aan, it might appear that their differences are many. cf. al-Qaaree, p. 140

451 Actually, there is a third level of narration, below that of raawi, called tareeq (path). Each raawi has two tareeqs. The differences between the turuq (pl. of tareeq) are negligible for our purposes, concentrating mainly on where to stop, certain variations in the particulars of pronunciation, etc. However, on some occasions there are noticeable differences. For example, compare a Qur’aan printed in Pakistan (Taj Company, for example) and one printed in Saudi Arabia or Egypt, and see 30:54. The difference in the words Da’fin and Du’fin are due to the differences in the turuq of the qiraa’a of Hafs ‘an ‘Aasim !

452 cf. az-Zarkashee, Bahr, pps, 474 – 480, for a discussion of this point.

453 The table was taken from al-Habash, p. 50. In this author’s opinion, he has greatly exaggerated the predominance of the qiraa’a of Ibn ‘Aamir ; ad-Dooree’s percentage should also be less ; Qaloon should be more than 0.7%. In addition, Hafs is probably closer to 97 than 95%, and Allaah knows best.

454 The Tayyibah is more advanced than the Shaatibiyyah-plus-Durrah combination, since Ibn al-Jazaree recorded more differences between the various turuq than ash-Shaatibee did.

455 cf. Itr, pps. 346 – 357

456 See the chapter entitled, “The Ahruf of the Qur’aan,” for a discussion of the existence of the ahruf today.

457 Actually, until it reached the ten Qaarees, and not just seven.

458 Ibn Abee Taalib, Abu Muhammad Makkee : Kitaab al-Ibaanah ‘an Ma’ani al-Qira’aat. ed. Dr. Muhyi Ramadaan. Dar al-Mamoon li Thurath, Beirut, 1979, p. 39

459 This is not to imply that the Qur’aan would have become monotonous had the qira’aat not existed, but rather that the different qira’aat are one of the factors that contribute to this miraculous effect. Any person who has dealth with the qira’aat knows this feeling.

460 Many of the differences in the qira’aat do not affect the meaning of a verse, but rather change only the pronunciation of certain vowels and letters. However, this section discusses only those differences that result in a change in meaning.

461 Adwaa al-Bayaan, v. 6, p. 680

462 al-Hamood, p. 88

463 Baazmool, v. 1, p. 403

464 In this verse in particular, the i’jaaz of the Qur’aan can be felt, for the very same verse is the command and response !

465 See Fiqh as-Sunnah, v.1, pps. 44 – 46, for further details on this issue.

466 az-Zarkashee, v.2, p. 52