Abstract

A recurring polemical claim in contemporary anti-Islamic media asserts that a narration attributed to ʿAbd Allāh b. Masʿūd and preserved in Musnad Aḥmad depicts figures identified as “al-Zuṭṭ” who “rode” the Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ in a sexually humiliating sense. This interpretation rests on a sensationalised English rendering of the Arabic verb يَرْكَبُونَ (yarkabūn) and has been most visibly popularised by Raymond Ibrahim, a far-right Christian polemicist widely known for his inflammatory anti-Muslim rhetoric. The claim first appeared in an article published by Raymond Ibrahim in 2022 and was later amplified through a 2025 YouTube video that achieved viral circulation. It was subsequently echoed by other Christian polemical outlets, chief among them being David Wood.

This article offers a comprehensive reassessment of the claim by examining the primary Arabic text, its internal narrative resolution, its isnād status, classical Arabic lexicography, and variant wordings within the report’s transmission family. It demonstrates that the polemical interpretation is not compelled by Arabic semantics. It also ignores decisive internal and external interpretive controls and relies instead on anachronistic slang substitution and rhetorical stacking of unrelated sexual material. The controversy is best understood as a case study in “innuendo translation,” wherein polysemy is exploited to manufacture scandal rather than to illuminate historical meaning.

Introduction

The use of translation as a polemical weapon is neither new nor unique to contemporary religious debate. What distinguishes the present controversy surrounding the al-Zuṭṭ and the alleged “riding” of the Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ is the degree to which a single Arabic verb has been isolated, decontextualised, and re-semanticised to sustain a scandal narrative. In modern Anglophone polemics, this claim is repeatedly presented as the unavoidable consequence of “literal Arabic.” Critics assert that Muslim scholars suppress an embarrassing text whose meaning is allegedly obvious to anyone who “knows the language.” As it was with the nursing of adults hadith, such claims rely heavily on rhetorical certainty and shock value, but they rarely withstand sustained philological scrutiny.

This article argues that the sexualised interpretation of the al-Zuṭṭ narration is a modern construction, dependent not on the Arabic text itself but on a sequence of methodological violations. These include isolation of a polysemous verb, suppression of narrative resolution, retrojection of modern English slang into classical Arabic, and amplification through ideologically aligned digital media. When the narration is read in its entirety, and when its language is evaluated according to classical Arabic usage and internal transmission controls, the scandal dissolves.

The Primary Narration and Its Structure

This analysis will clarify the meaning of the controversial terms used in this narration and emphasize the importance of contextual understanding.

The report attributed to ʿAbd Allāh b. Masʿūd appears in Musnad Aḥmad1 within a cluster of narrations describing nocturnal encounters and revelatory experiences :

إن عبدالله قال إستبعثني رسول الله ﷺ قال فانطلقنا حتى أتيت مكان كذا وكذا فخطَّ لي خطة فقال لي كن بين ظهرَي هذه لا تخرج منها فإنك إن خرجت هلكتَ قال فكنت فيها قال فمضى رسول الله ﷺ خَذَفة أو أبعد شيئاً أو كما قال ثم إنه ذكر هنيناً كأنهم الزُطّ قال عفان أو كما قال عفان إن شاء الله ليس عليهم ثياب ولا أرى سوءاتهم طوالاً قليل لحمهم قال فأتوا فجعلوا يركبون رسول الله ﷺ قال وجعل نبي الله ﷺ يقرأ عليهم قال وجعلوا يأتوني فيخيِّلون أو يميلون حولي ويعترضون لي قال عبدالله فاُرعبتُ منهم رُعباً شديداً قال فجلست أو كما قال قال فلما إنشقَّ عمود الصبح جعلوا يذهبون أو كما قال قال ثم إن رسول الله ﷺ جاء ثقيلاً وَجِعاً أو يكاد أن يكون وجعاً مما ركِبوه قال إني لأجدني ثقيلاً أو كما قال فوضع رسول الله ﷺ رأسه في حجري أو كما قال قال ثم إن هنيناً أتوا عليهم ثياب بيض طوال أو كما قال وقد أغفى رسول الله ﷺ قال عبدالله فارعبت منهم أشد مما اُرعبت المرة الاولى

قال عارم في حديثه فقال بعضهم لبعض لقد اُعطي هذا العبد خيراً أو كما قالوا إن عينيه نائمتان أو قال عينيه أو كما قالوا وقلبه يقظان ثم قال قال عارم وعفان قال بعضهم لبعض هلم فلنضرب له مثلاً أو كما قالوا قال بعضهم لبعض اضربوا له مثلاً ونؤوِّل نحن أو نضرب نحن وتؤوِّلون أنتم فقال بعضهم لبعض مثله كمثل سيد ابتنى بنياناً حصيناً ثم أرسل إلى الناس بطعام أو كما قال فمن لم يأت طعامه أو قال لم يتبعه عذّبه عذاباً شديداً أو كما قالوا قال الآخرون أما السيد فهو رب العالمين وأما البنيان فهو الاسلام والطعام الجنة وهو الداعي فمن اتّبعه كان في الجنة قال عارم في حديثه أو كما قال ومن لم يتبعه عُذِّب أو كما قال ثم إن رسول الله ﷺ إستيقظ فقال ما رأيت يا إبن أم عبد فقال عندالله رأيت كذا وكذا فقال نبي الله ﷺ ما خُفي عليّ مما قالوا شيء قال نبي الله ﷺ هم نفر من الملائكة أو قال هم من الملائكة أو كما شاء الله

Inna ʿAbdallāha qāla : istabʿathanī Rasūlu Llāhi ﷺ. Qāla : fanṭalaqnā ḥattā ataytu makāna kadhā wa-kadhā, fakhaṭṭa lī khaṭṭatan faqāla lī : kun bayna ẓahray hādhihi lā takhruj minhā fa-innaka in kharajta halakta. Qāla : fakuntu fīhā. Qāla : famaḍā Rasūlu Llāhi ﷺ khaḏfatan aw abʿada shayʾan aw kamā qāl. Thumma innahu dhakara hanīnan ka-annahum az-Zuṭṭ. Qāla ʿAffān aw kamā qāla ʿAffān in shāʾa Llāh : laysa ʿalayhim thiyāb wa-lā arā sawʾātihim ṭiwālan qalīla laḥmihim. Qāla : fa-ataw fa-jaʿalū yarkabūna Rasūla Llāhi ﷺ. Qāla : wa-jaʿala Nabiyyu Llāhi ﷺ yaqraʾu ʿalayhim. Qāla : wa-jaʿalū yaʾtūnanī fayukhayyilūna aw yamīlūna ḥawlayya wa-yaʿtariḍūna lī. Qāla ʿAbdullāh : fa-urʿibtu منهم ruʿban shadīdan. Qāla : fajalasstu aw kamā qāl. Qāla : falammā inshaqqa ʿamūdu ṣ‑ṣubḥ jaʿalū yadhhabūna aw kamā qāl. Qāla : thumma inna Rasūla Llāhi ﷺ jāʾa thaqīlan wajiʿan aw yakādu an yakūna wajiʿan mimmā ركibūhu. Qāla : innī la-ajidu-nī thaqīlan aw kamā qāl. Fawaḍaʿa Rasūlu Llāhi ﷺ raʾsahu fī ḥijrī aw kamā qāl. Qāla : thumma inna hanīnan ataw ʿalayhim thiyābun bīḍ ṭiwāl aw kamā qāl, wa-qad aghfā Rasūlu Llāhi ﷺ. Qāla ʿAbdullāh : fa-urʿibtu منهم ashaddu mimmā urʿibtu al-marrah al-ūlā.

Qāla ʿĀrim fī ḥadīthihī : faqāla baʿḍuhum li-baʿḍ : laqad uʿṭiya hādhā al-ʿabdu khayran aw kamā qālū. Inna ʿaynayhi nāʾimatān aw qālū ʿaynayhi aw kamā qālū, wa-qalbuhu yaqẓān. Thumma qāla : qāla ʿĀrim wa-ʿAffān : qāla baʿḍuhum li-baʿḍ : halummū falnaḍrib lahu mathalan aw kamā qālū. Qāla baʿḍuhum li-baʿḍ : iḍribū lahu mathalan wa-nuʾawwilu naḥnu aw naḍribu naḥnu wa-tuʾawwilu antum. Faqāla baʿḍuhum li-baʿḍ : mathaluhu ka-mathali sayyidin ibtanā bunyānan ḥaṣīnan thumma arsala ilā an-nās bi-ṭaʿāmin aw kamā qāl, fa-man lam yaʾti ṭaʿāmahu aw qāl lam yattabiʿhu ʿadhdhabahu ʿadhāban shadīdan aw kamā qālū. Qāla al-ākharūn : ammā as-sayyidu fahuwa Rabbu al-ʿālamīn, wa-ammā al-bunyānu fahuwa al-Islām, wa-aṭ-ṭaʿāmu al-Jannah, wa-huwa ad-dāʿī ; fa-man ittabaʿahu kāna fī al-Jannah. Qāla ʿĀrim fī ḥadīthihī aw kamā qāl : wa-man lam yattabiʿhu ʿuḏḏhiba aw kamā qāl. Thumma inna Rasūla Llāhi ﷺ istayqaẓa faqāla : mā raʾayta yā Ibn Ummi ʿAbd ? Qāla : ʿinda Llāh raʾaytu kadhā wa-kadhā. Faqāla Nabiyyu Llāhi ﷺ : mā khufiya ʿalayya mimmā qālū shayʾ. Qāla Nabiyyu Llāhi ﷺ : hum nafarun mina al-malāʾikah aw qāla hum mina al-malāʾikah aw kamā shāʾa Llāh.

Translation :

ʿAbdullāh ibn Mas’ud said : The Messenger of God ﷺ sent me. He said : “We set out until I reached such-and-such a place. He drew a line for me and said, ‘Remain between these two sides and do not leave it. If you leave it, you will perish.’”

He said : So I stayed within it. Then the Messenger of God ﷺ went a short distance — or farther away, or as he said. Then he mentioned beings like hanīn, as though they were the Zuṭṭ. ʿAffān said — or as ʿAffān said, God willing — that they had no clothes, and I did not see their private parts ; they were tall and lean, with little flesh. They came and began to yarkabūn the Messenger of God ﷺ. The Prophet of God ﷺ began reciting to them.

They came to me, making it seem to me — or leaning around me — and obstructing me. ʿAbdullāh said : I was struck with intense fear of them. So I sat— or as he said. When the pillar of dawn split, they began to depart — or as he said. Then the Messenger of God ﷺ returned heavy and aching, or nearly aching, from what they had mounted upon him. He said : “I feel heavy,” or as he said. The Messenger of God ﷺ placed his head in my lap — or as he said.

Then the hanīn came again, wearing long white garments — or as he said — while the Messenger of God ﷺ had fallen asleep. ʿAbdullāh said : I was even more frightened of them than I had been the first time.

ʿĀrim said in his narration : Some of them said to one another, “This servant has been given great good,” or as they said. “His eyes are asleep” — or they said “his eyes,” or as they said — “but his heart is awake.” Then ʿĀrim and ʿAffān said : Some of them said to one another, “Come, let us strike a parable for him,” or as they said. Some said, “You strike the parable and we will interpret it,” or “we strike it and you interpret it.”

So some of them said : “His likeness is that of a master who built a fortified structure, then invited people to a feast — or as he said. Whoever did not come to his feast,” or “did not follow him,” “he punished with a severe punishment,” or as they said. The others said : “As for the master, he is the Lord of the worlds ; the structure is Islam ; the feast is Paradise ; and he is the caller. Whoever follows him will be in Paradise.” ʿĀrim said in his narration — or as he said — “and whoever does not follow him will be punished.”

Then the Messenger of God ﷺ awoke and said : “What did you see, O Ibn Umm ʿAbd?”

I said : “By God, I saw such-and-such.”

The Prophet of God ﷺ said : “Nothing of what they said was hidden from me.”

The Prophet of God ﷺ said : “They are a group of angels,” or “they are from among the angels,” as God willed.

In the narration under discussion, Ibn Masʿūd recounts that the Prophet ﷺ took him to a place at night, drew a protective boundary for him, and instructed him not to leave it. Ibn Masʿūd then reports the appearance of figures whom he describes using a simile : كَأَنَّهُمُ الزُّطّ (“as though they were al-Zuṭṭ”). The controversial clause follows : فَأَتَوْا فَجَعَلُوا يَرْكَبُونَ رَسُولَ الله ﷺ (“Then they came and began to yarkabūn the Messenger of God”). Here, the polemicists render the word yarkabūn as “ride” or “mount”.

Polemical treatments almost invariably arrest the narration at this point, treating the clause as self-explanatory and scandalous. Yet the report continues. After further description of fear, exhaustion, and symbolic discourse, the narration concludes with the Prophet ﷺ explicitly identifying the figures : هُمْ نَفَرٌ مِنَ الْمَلَائِكَةِ (“They were a group of angels”).

The al-Zuṭṭ hadith polemic thus serves as a revealing case study in what may be termed innuendo translation : a practice in which semantic range is weaponised to manufacture scandal rather than to recover historical meaning. Recognising this does not require theological commitment or apologetic defence ; it requires only adherence to the basic disciplines of textual analysis, lexicography, and narrative reading.

If we read the Musnad report of the the al-Zuṭṭ hadith as a narrative, not as a scandal meme, the storyline is coherent without sexual content :

- Ibn Masʿūd is placed under protection (boundary in the sand).

- Strange figures appear “as if they were al-Zuṭṭ.”

- They press toward the Prophet ﷺ and toward Ibn Masʿūd but cannot cross the boundary.

- Ibn Masʿūd is terrified.

- The Prophet ﷺ returns feeling heavy and tired from the overcrowding.

- The visitors later appear clothed in white.

- The Prophet ﷺ identifies them as angels.

If anything, the narrative’s “pressure” language fits the ازدحموا عليه gloss (“they crowded onto him”) far more naturally than the polemical fantasy. The narration itself confirms this reading. The resemblance is provisional, while the final identification — as angels — is authoritative. To collapse simile into identity is not an act of linguistic clarification but a deliberate narrowing of meaning designed to sustain a polemical outcome.

The Semantics of يركبون (yarkabūn)

The core of the al-Zuṭṭ hadith polemic centers on the Arabic verb يَرْكَبُونَ (yarkabūn). In classical Arabic, the root r‑k-b denotes riding or mounting, with well-attested metaphorical extensions such as pressing upon, crowding, or overtaking :

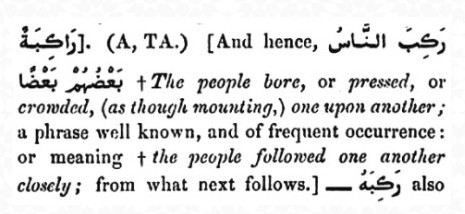

Lane’s Arabic – English Lexicon identifies “mount/ride/embark” as the core semantic field and also records the idiom :

رَكِبَ النَّاسُ بَعْضُهُمْ بَعْضًا (rakiba al-nasu baʿḍuhum baʿḍan) — the people bore, or pressed, or crowded (as though mounting) one upon another ; a phrase well known, and of frequent occurrence.2

Lisān al-ʿArab likewise anchors ركب in physical riding and its derivative senses, not in sexual meaning as a default lexical value.

Within the same transmission family, the disputed action in the al-Zuṭṭ hadith polemic is glossed as ازدحموا عليه (“they crowded onto him”). This variant provides an internal interpretive control, indicating that early transmitters understood the episode as crowding rather than anything erotic. Once this evidence is acknowledged, a sexualized reading loses linguistic plausibility.

Although Arabic can employ “mounting” verbs euphemistically in sexual contexts, such usage requires explicit contextual signals — objects, idioms, or genre markers — that are absent here. The narration instead describes a public event accompanied by recitation and followed by symbolic and theological commentary, reinforcing a non-sexual reading.

The insinuation arises not from Arabic semantics but from modern English interference. In contemporary slang, “ride” may carry erotic connotations ; polemical translations exploit this by importing colloquial English meaning into a classical Arabic register, thereby committing a register error in which a modern, culture-specific sense is retrojected into a historical linguistic environment where it does not belong. What is presented as a “literal” rendering is therefore not a recovery of historical meaning, but a substitution of contemporary slang for classical semantic norms.

This maneuver is best understood as obscene projection rather than translation. The interpretive move operates less like philology and more like vulgar double-entendre : a classical term is isolated from its discursive environment, stripped of its premodern semantic constraints, and re-coded to yield a sensational effect never intended by the original language. The obscenity does not reside in the historical source itself, but in the polemicist’s intrusive framework, which substitutes insinuation for evidence and shock for semantic accountability.

Illustration of innuendo translation, where obscenity is imposed by the interpreter rather than discovered in the source.

Comparative philology further undermines the polemic. The Arabic root ر‑ك-ب is a direct cognate of the Hebrew ר‑כ-ב (r‑k-b), both deriving from a shared Proto-Semitic base whose primary sense concerns riding or mounting. Across Semitic languages, any erotic usage emerges only as a marked, context-bound extension rather than a narrative default. A sexualized reading of يركبون would therefore violate not only Arabic usage in this report but the inherited semantic structure of the broader Semitic family.3

In Biblical Hebrew, the root רכב (rākav, “to ride”) is frequently employed in figurative and metaphorical expressions of domination, elevation, or triumph, without any sexual implication.

Psalm 66:12 states :

הִרְכַּבְתָּ אֱנוֹשׁ לְרֹאשֵׁנוּ

“You caused men to ride over our heads” .4

Here, “riding” expresses oppression and subjugation, not physical mounting in any literal sense.

Likewise, Isaiah 58:14 declares :

וְהִרְכַּבְתִּיךָ עַל־בָּמֳתֵי אָרֶץ

“I will make you ride upon the heights of the earth”.5

No interpreter suggests a bodily or sexual act ; the verb conveys exaltation and dominion. To impose modern sexual slang onto these verses would be recognised immediately as interpretive malpractice. The verb’s semantic range does not license erotic retrojection.

The same principle governs New Testament Greek. In Luke 10:34, the evangelist writes of the wounded man in the parable of the Good Samaritan :

ἐπιβιβάσας δὲ αὐτὸν ἐπὶ τὸ ἴδιον κτῆνος

“He set him upon his own animal” .6

The verb ἐπιβιβάζω, derived from ἐπιβαίνω (“to mount, to board”), denotes physical placement upon an animal for transport. No sexual implication is conceivable within the narrative genre.

Similarly, Acts 21:2 uses ἐπιβαίνω for boarding a ship :

καὶ ἐπιβάντες εἰς πλοῖον

“And having boarded a ship…”.7

The semantic core is motion and contact, not eroticism.

Crucially, however, Greek lexicography demonstrates that these same verbs can acquire sexual or reproductive meanings outside biblical narrative, particularly in animal-breeding contexts or erotic metaphor. Pollux, in his Onomasticon, lists ἐπιβαίνειν among verbs used for animal copulation :

τὸ μίγνυσθαι ἐπὶ μὲν τῶν ἀλόγων βαίνειν, ἐπιβαίνειν, ὀχεύειν…

“To mate : of animals, [the verbs] ‘to go upon,’ ‘to mount,’ ‘to copulate’…” .8

Modern scholarship confirms this usage, noting that ἐπιβαίνω can denote “reproductive animals mounting a female” in technical contexts. Interestingly also, ἐπιβαίνω can carry an“obscene allusion” in Greek comedy usage by Aristophanes, and explicitly connects that to ἐπιβαίνω being used obscenely (“to mount”) by analogy with animals. Yet no scholar would therefore read Luke 10:34 or Acts 21:2 as sexually suggestive. The genre, narrative context, and syntactic environment strictly delimit meaning.

This comparison exposes the fallacy at work in the al-Zuṭṭ hadith polemic. The Arabic يَرْكَبُونَ, like Hebrew רכב and Greek ἐπιβαίνω, possesses a broad semantic range. Sexual meaning exists only as a secondary, context-dependent extension, never as a default. To isolate the verb, ignore its narrative environment, suppress internal clarifications, and then import a modern colloquial meaning is not translation but insinuation. It is precisely the same abuse that would be required to sexualise large portions of the Hebrew Bible and New Testament — an abuse that no responsible scholar countenances.

What emerges is a recognizable rhetorical pattern : polysemy is exploited, narrative coherence is ignored, and modern slang is substituted for classical meaning to manufacture scandal. This “innuendo translation” depends on suggestion and repetition rather than philology, and collapses under linguistic, comparative, and contextual scrutiny.

Conclusion

A careful examination of the al-Zuṭṭ hadith narration attributed to ʿAbd Allāh b. Masʿūd demonstrates that the sexualised interpretation of the al-Zuṭṭ episode is neither linguistically compelled nor narratively coherent. The claim rests on the isolation of a polysemous verb, the suppression of internal interpretive controls, and the retrojection of modern English slang into classical Arabic. When the narration is read in full, its structure is clear : provisional perception gives way to authoritative clarification, and physical crowding is framed within a visionary encounter, culminating in the identification of the figures as angels.

Comparative evidence from Biblical Hebrew and New Testament Greek confirms that such abuse of polysemy is not unique to Arabic polemics but represents a general methodological failure. Verbs meaning “ride” or “mount” do not default to sexual meaning ; they acquire such meanings only under specific contextual and generic conditions. To ignore those conditions is to abandon philology in favour of insinuation.

The al-Zuṭṭ hadith polemic thus serves as a revealing case study in what may be termed innuendo translation : a practice in which semantic range is weaponised to manufacture scandal rather than to recover historical meaning. Recognising this does not require theological commitment or apologetic defence. It requires only adherence to the basic disciplines of textual analysis, lexicography, and narrative reading. When those disciplines are applied consistently, the polemical edifice collapses under its own methodological weight.

When these disciplines are applied consistently, the polemical edifice collapses under its own methodological weight. The sexualised reading of the al-Zuṭṭ hadith polemic lacks any credible support from philological evidence. And only God knows best !

Frequently-Asked Questions

What is the “al-Zuṭṭ riding the Prophet Muhammad” allegation ?

The allegation claims that a hadith in Musnad Aḥmad portrays figures called “al-Zuṭṭ” sexually “riding” Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ. This narrative originates from modern anti-Islam polemics and relies on a sensationalised mistranslation of the Arabic verb يَرْكَبُونَ (yarkabūn).

Does the hadith actually describe a sexual act involving the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ ?

No. A full reading of the Arabic text shows no sexual content. The narration depicts a visionary nighttime encounter that concludes with the Prophet ﷺ identifying the figures as angels. The sexualised interpretation emerges from selective quoting and modern slang substitution, not from the original Arabic meaning.

What does the Arabic verb yarkabūn (يركبون) mean in classical usage ?

In classical Arabic, yarkabūn derives from the root ر‑ك-ب and commonly means to ride, mount, press upon, crowd, or board. While the root can carry sexual meaning in certain explicit contexts, there are no such contextual signals in this hadith.

Are there variant hadith wordings that clarify the meaning ?

Yes. Other narrations within the same transmission family gloss the disputed action as ازدحموا عليه (“they crowded onto him”). This serves as an internal interpretive control confirming that early transmitters understood the event as crowding rather than sexual behavior.

Why is this case considered an example of “innuendo translation”?

Because polemicists isolate a polysemous Arabic word, ignore narrative context, suppress clarifying variants, and impose modern English sexual slang onto a classical religious text. This method manufactures scandal instead of recovering historical or linguistic meaning.

Do Hebrew and Greek parallels support the polemical interpretation ?

No. Related verbs in Biblical Hebrew (רכב) and New Testament Greek (ἐπιβαίνω) primarily mean “ride” or “mount” in neutral or metaphorical senses. Sexual meanings appear only in marked, context-specific cases. Scholarly standards reject importing erotic connotations into neutral sacred narratives, and the same principle applies here.

- Aḥmad b. Ḥanbal, al-Musnad, ḥadīth no. 3788, was graded ḍaʿīf (weak) by Shuʿayb al-Arnāʾūṭ et al., whereas Aḥmad Shākir classified it as ṣaḥīḥ. A similar report is narrated in Jami’ Al-Tirmidhī 2861 but without the mention of “crowding”.[⤶]

- E. W. Lane, Arabic-English Lexicon, (Beirut : Librairie du Liban, 1968) Book I, Part 3, 1142.[⤶]

- See Lane, Arabic – English Lexicon, s.v. ركب ; Ibn Manẓūr, Lisān al-ʿArab, s.v. ركب ; Brown – Driver – Briggs, Hebrew and English Lexicon, s.v. רכב ; Koehler & Baumgartner, HALOT, s.v. רכב ; Moscati et al., Comparative Grammar of the Semitic Languages ; Rubin, Brief Introduction to the Semitic Languages ; Barr, The Semantics of Biblical Language.[⤶]

- Psalms 66:12[⤶]

- Isaiah 58:14[⤶]

- Luke 10:34[⤶]

- Acts 21:2[⤶]

- Pollux, Onom. 5.92[⤶]