Abstract

The marriage of Aisha to the Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ has long been a focal point of polemical criticism, particularly in Christian missionary discourse, Islamophobic media, and ex-Muslim activist narratives. These critiques frequently rest on anachronistic moral judgments that impose contemporary Western cultural and legal standards onto the moral world of seventh-century Arabia. Such readings fail to account for the historical norms governing puberty, marriage, legal adulthood, and social responsibility in premodern societies.

This study argues that evaluating the marriage requires historical contextualisation, legal-anthropological analysis, medical and biological realism regarding puberty, comparative civilisational evidence, and ethical caution against the fallacy of presentism. Drawing upon Islamic primary sources, classical juristic frameworks, comparative Jewish and Christian traditions, anthropological research, modern historical scholarship, and moral theory, it concludes that the marriage was consistent with the accepted social norms of its time and cannot reasonably be construed as sexual predation or pedophilia under either historical or clinical definitions. Rather than revealing moral deviance, the evidence supports the conclusion that this marriage occurred within a coherent ethical and social framework that modern polemics often misunderstand or deliberately distort.

Introduction

Sadly, we currently observe intensified efforts by Christian missionary movements, Islamophobic commentators, and ideological critics to derail Islam through renewed fixation on the marriage of the Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ to ʿĀʾishah bint Abī Bakr. These polemical campaigns increasingly rely on sensationalism, selective quotation, and rhetorical caricature rather than sober historical analysis. As a result, historical, linguistic, and legal realities are frequently twisted, manipulated, or stripped of their proper context, producing narratives that range from intellectually unserious to overtly abusive.

One of the most persistent allegations advanced in this discourse is that the Prophet ﷺ engaged in child abuse or sexual immorality due to reports concerning ʿĀʾishah’s age at marriage. Critics often frame the issue in politically sanitized language such as “child marriage,” “statutory rape,” or “pedophilia,” importing modern Western moral categories into a premodern cultural setting. These claims, however, rest not on careful historical reasoning but on conjecture, ideological animus, and retrospective moral projection. The marriage occurred roughly fourteen centuries ago in a society whose legal, biological, and moral assumptions differed fundamentally from those of the modern West.

Although these polemics would merit little attention were it not for their public influence, their persistence and circulation necessitate scholarly response. This study addresses the allegation by situating the marriage within its authentic historical context, demonstrating that it accords with prevailing norms of seventh-century Arabia and broader Semitic civilisation rather than constituting deviant or abusive conduct.

Hadith Sources on the Marriage of ʿĀʾishah and Muḥammad

The primary textual evidence regarding the age of ʿĀʾishah at marriage is found in canonical Sunni hadith collections, most prominently Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī and Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim. Among the most widely cited narrations is the report transmitted on the authority of ʿĀʾishah herself, recorded in Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, Kitāb al-Nikāḥ, ḥadīth no. 5134 (in the Fatḥ al-Bārī numbering) and parallel reports elsewhere in the collection. The Arabic text states :

قَالَتْ عَائِشَةُ رَضِيَ اللَّهُ عَنْهَا : تَزَوَّجَنِي النَّبِيُّ صَلَّى اللَّهُ عَلَيْهِ وَسَلَّمَ وَأَنَا بِنْتُ سِتِّ سِنِينَ، وَبَنَى بِي وَأَنَا بِنْتُ تِسْعِ سِنِينَ

“ʿĀʾishah, may Allah be pleased with her, said : The Prophet ﷺ married me when I was six years old, and he consummated the marriage with me when I was nine years old.” 1

A closely corresponding narration appears in Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, likewise attributed to ʿĀʾishah. The Arabic wording affirms the same chronological sequence, distinguishing between the conclusion of the marriage contract and the later act of consummation :

حَدَّثَنَا أَبُو كُرَيْبٍ، مُحَمَّدُ بْنُ الْعَلاَءِ حَدَّثَنَا أَبُو أُسَامَةَ، ح وَحَدَّثَنَا أَبُو بَكْرِ بْنُ أَبِي، شَيْبَةَ قَالَ وَجَدْتُ فِي كِتَابِي عَنْ أَبِي أُسَامَةَ، عَنْ هِشَامٍ، عَنْ أَبِيهِ، عَنْ عَائِشَةَ، قَالَتْ تَزَوَّجَنِي رَسُولُ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم لِسِتِّ سِنِينَ وَبَنَى بِي وَأَنَا بِنْتُ تِسْعِ سِنِينَ . قَالَتْ فَقَدِمْنَا الْمَدِينَةَ فَوُعِكْتُ شَهْرًا فَوَفَى شَعْرِي جُمَيْمَةً فَأَتَتْنِي أُمُّ رُومَانَ وَأَنَا عَلَى أُرْجُوحَةٍ وَمَعِي صَوَاحِبِي فَصَرَخَتْ بِي فَأَتَيْتُهَا وَمَا أَدْرِي مَا تُرِيدُ بِي فَأَخَذَتْ بِيَدِي فَأَوْقَفَتْنِي عَلَى الْبَابِ . فَقُلْتُ هَهْ هَهْ . حَتَّى ذَهَبَ نَفَسِي فَأَدْخَلَتْنِي بَيْتًا فَإِذَا نِسْوَةٌ مِنَ الأَنْصَارِ فَقُلْنَ عَلَى الْخَيْرِ وَالْبَرَكَةِ وَعَلَى خَيْرِ طَائِرٍ . فَأَسْلَمَتْنِي إِلَيْهِنَّ فَغَسَلْنَ رَأْسِي وَأَصْلَحْنَنِي فَلَمْ يَرُعْنِي إِلاَّ وَرَسُولُ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم ضُحًى فَأَسْلَمْنَنِي إِلَيْهِ.

‘A’isha (Allah be pleased with her) reported :

Allah’s Messenger (ﷺ) married me when I was six years old, and I was admitted to his house at the age of nine. She further said : We went to Medina and I had an attack of fever for a month, and my hair had come down to the earlobes. Umm Ruman (my mother) came to me and I was at that time on a swing along with my playmates. She called me loudly and I went to her and I did not know what she had wanted of me. She took hold of my hand and took me to the door, and I was saying : Ha, ha (as if I was gasping), until the agitation of my heart was over. She took me to a house, where had gathered the women of the Ansar. They all blessed me and wished me good luck and said : May you have share in good. She (my mother) entrusted me to them. They washed my head and embellished me and nothing frightened me. Allah’s Messenger (may peace be upon him) came there in the morning, and I was entrusted to him.2

These narrations are graded ṣaḥīḥ within the Sunni hadith canon and were accepted by early Muslim scholars without being treated as ethically problematic or historically suspect.

These narrations explicitly distinguish between the conclusion of the marriage contract (zawāj) and the later act of consummation (nikāḥ/dukhūl). The interval between these events strongly suggests that consummation was delayed until physical maturity was reached, indicating parental oversight rather than impropriety.

Jonathan A. C. Brown has noted that this pattern aligns with broader premodern marriage practices, in which legal contracts often preceded physical cohabitation by several years :

Historical and Biological Context of Early Marriage

Puberty and Adulthood in Premodern Societies

A central weakness in modern polemical attacks lies in their disregard for historical definitions of adulthood. In Semitic cultures, including Arab and Israelite societies, puberty rather than chronological age traditionally marked the transition to adult social status. Menstruation, in particular, was widely recognised as a biological sign of reproductive readiness and a girl becomes a woman when she begins her menstruation cycle and is being prepared to become a mother.

Physiological research indicates that girls typically reach puberty between eight and twelve years of age, with variation determined by genetics, race, nutrition, and environmental conditions. Educational and medical sources observe that pubertal growth begins earlier in girls than in boys and that the first signs of puberty commonly appear around ages nine or ten.

We read that :

There is little difference in the size of boys and girls until the age of ten, the growth spurt at puberty starts earlier in girls but lasts longer in boys.3

We also read that :

The first signs of puberty occur around age 9 or 10 in girls but closer to 12 in boys[.]4

Women in warmer environments reach puberty at a much earlier age than those in cold environments.

“The average temperature of the country or province is considered the chief factor here, not only with regard to menstruation but as regards the whole of sexual development at puberty.“5

Modern pediatric and gynecological research establishes an important distinction between the onset of menstruation (menarche) and full physical readiness for pregnancy and childbirth. While menarche typically occurs between ages 9 – 14 in contemporary populations, the biological processes supporting safe pregnancy continue developing for several years thereafter. Contemporary medical literature indicates that optimal reproductive health requires skeletal maturity, particularly pelvic development, which continues into the mid-to-late teenage years.6

This medical reality adds contextual depth to the three-year interval between the marriage contract and consummation in ʿĀʾishah’s case. Rather than indicating impropriety, this delay demonstrates a pattern consistent with awaiting not merely the onset of menstruation but a more comprehensive physical maturity. The hadith literature preserves details suggesting careful attention to ʿĀʾishah’s readiness : the preparation by women of the Anṣār, the involvement of her mother Umm Rūmān, and the community’s oversight of the transition all indicate structured social protocols rather than precipitous action.

Classical Islamic jurisprudence reflects similar caution. While various schools of law acknowledged puberty as a threshold for marital eligibility, jurists extensively debated the conditions under which consummation could proceed. The Ḥanafī school, for instance, distinguished between legal capacity (established by puberty signs) and physical readiness (determined by the bride’s ability to “endure intercourse” without harm). Imām al-Kāsānī (d. 1189 CE) wrote in Badāʾiʿ al-Ṣanāʾiʿ :

“If the wife is a minor, it is not permissible for the husband to have intercourse with her until she becomes capable of intercourse… the criterion is her physical capacity to endure it without suffering harm.“7

Similarly, Mālikī jurists required that the bride be physically mature enough that intercourse would not cause injury (ḍarar), interpreting this as a condition beyond mere menstruation. Ibn Rushd (Averroes, d. 1198 CE) notes in Bidāyat al-Mujtahid that scholars disagreed on whether a specific age threshold should supplement puberty indicators, with some requiring additional time beyond menarche.8

The three-year waiting period in the Prophet’s marriage thus aligns with a prudential framework that later Islamic jurisprudence would systematize : legal marriage at puberty, but delayed consummation pending fuller maturity. This pattern contradicts allegations of reckless or predatory behavior and instead demonstrates ethical deliberation calibrated to biological and social readiness.

Marriage Practices Across Semitic and Christian Civilizations

Within this biological and cultural context, early post-pubertal marriage was socially accepted in seventh-century Arabia and throughout Semitic civilisation. Rabbinic Jewish sources such as the Talmud discuss marriage in relation to the onset of menstruation, with legal material in Sanhedrin 76b and Ketuvot 6a addressing marital eligibility and sexual relations.

This further collaborates what Jim West said when he observes the following tradition of the Israelites :

The wife was to be taken from within the larger family circle (usually at the outset of puberty or around the age of 13) in order to maintain the purity of the family line.9

Across cultures, puberty has historically functioned as a symbol of adulthood and social readiness. Anthropological literature identifies puberty rites as a universal marker of transition into adult responsibilities, including marriage and reproduction :

“Puberty is defined as the age or period at which a person is first capable of sexual reproduction, in other eras of history, a rite or celebration of this landmark event was a part of the culture.“10

Studies of Afro-Asian sexual norms further observe that in parts of North Africa, Arabia, and India, girls have historically been married shortly after reaching puberty and that remaining unmarried beyond puberty was socially discouraged :

“Today, in many parts of North Africa, Arabia, and India, girls are wedded and bedded between the ages of five and nine ; and no self-respecting female remains unmarried beyond the age of puberty.“11

Let us now look at the circumstances surrounding the marriage of Rebekah to Isaac, the patriarch of the Children of Israel, according to the Bible. Rabbi Tobiah Ben Eliezer (1050 – 1108 CE) confirms that she was 3 years old when she was married off to Isaac :

“Isaac was thirty-seven-years old at his binding…when Abraham returned from Mount Moriah, at that very moment Sarah died, and Isaac was then thirty-seven ; and at that very time Abraham was told of Rebekah’s birth ; thus we find that Rebecca was three years old when she married Isaac.“12

Isaac waited three years until Rebecca was fit for marital relations, which would only make Rebecca three years old at the time of consummation. From this, it seems Jewish scholars derived an age of consummation which is then reflected in the Talmud :

In Sanhedrin 55 :

“R. Joseph said : Come and hear ! A maiden aged three years and a day may be acquired in marriage by coition, and if her deceased husband’s brother cohabits with her, she becomes his.“13

This is reiterated again elsewhere in the Talmud :

“R. Jeremiah of Difti said : We also learnt the following : A maiden aged three years and a day may be acquired in marriage by coition, and if her deceased husband’s brother cohabited with her, she becomes his.“14

A female less than 3 years old, her intercourse is not considered as intercourse, and her virginity returns (Hagahot Yevamot). Even if the years were intercalated (e.g she had intercourse at 37 months old in a leap year) her virginity returns (words of the Rav, based on Yerushalmi Ketuboth chapter 1).15

While modern audiences may find these traditions troubling, they demonstrate that extremely young marriage norms were discussed within Jewish legal discourse and cannot be uniquely attributed to Islamic culture.

Christian Sacred Tradition and Early Marriage

Christian sacred tradition similarly affirms early marriage in the figure of Mary, mother of Jesus. While the canonical Gospels do not specify Mary’s age at betrothal to Joseph, early Christian extrabiblical sources provide explicit testimony.

The Protoevangelium of James (also called the Infancy Gospel of James), dating to the mid-second century CE and widely influential in shaping Christian Marian piety, describes Mary as twelve years old when she was betrothed :

“And she was twelve years old when the priests took counsel together, saying, ‘Behold Mary has reached the age of twelve years in the temple of the Lord. What then shall we do with her, lest perchance she defile the sanctuary of the Lord?’ ”16

The text proceeds to describe how Joseph, described as an elderly widower with children from a previous marriage, was divinely selected to serve as Mary’s guardian and husband. Subsequent passages depict the Annunciation and virgin birth occurring while Mary remained in Joseph’s care.

The History of Joseph the Carpenter, a Coptic Christian text likely composed in the fourth or fifth century, states explicitly that Joseph was ninety years old when he took Mary as his wife :

“I am an old man, and have children, but she is a young girl.“17

This account portrays Joseph as approximately 90 years old at the betrothal, with Mary aged twelve. Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Catholic iconographic and liturgical traditions have consistently depicted Joseph as elderly and Mary as youthful, reflecting these early textual traditions.

While modern Christian theologians often emphasize the chaste nature of Mary and Joseph’s relationship — understanding their marriage as unconsummated or undertaken solely for Mary’s protection — this theological interpretation does not alter the historical datum : Christian sacred tradition affirms that a twelve-year-old girl was betrothed to an elderly man, a union regarded not as scandalous but as divinely ordained.

If twelve year old Mary’s betrothal to ninety-year-old Joseph is defensible within Christian salvation history, then consistency demands that ʿĀʾishah’s marriage at a similar developmental stage cannot be uniquely condemned without exposing Christian critics to charges of hypocrisy.

Roman and Christian Legal Frameworks

Roman law, which profoundly shaped Christian legal traditions, established minimum ages for marriage that modern audiences would regard as extraordinarily young. Under classical Roman law (ius civile), the minimum age for marriage was set at puberty : twelve years for girls (puellae) and fourteen for boys (pueri).

The Digest of Justinian (6th century CE), which codified centuries of Roman legal tradition, explicitly states :

“It has been decided that a girl becomes marriageable from the completion of her twelfth year.“18

This legal threshold was not a theoretical minimum but the operative standard across the Roman Empire, including its Christian period following Constantine’s conversion in the fourth century. Roman law did not merely permit marriage at twelve but treated it as legally valid and binding, with full marital rights and responsibilities attaching immediately.

Early Christian authorities, far from rejecting these norms, incorporated them into canon law. The Roman legal age of twelve for girls and fourteen for boys was adopted by the Church and remained canon law for over a millennium.

Medieval Canon Law and Theological Authorities

The Council of Westminster (1175 CE) and subsequent ecclesiastical legislation established detailed regulations for Christian marriage, confirming the Roman ages :

- Age 7 : Children could be betrothed (sponsalia de futuro), creating a legally binding promise of future marriage.

- Age 12 (girls) /14 (boys): Full capacity for valid marriage (sponsalia de praesenti), including consummation.

Pope Alexander III (1159 – 1181 CE) issued decretals confirming that marriage contracted at these ages was valid and indissoluble, even if consummated immediately. His rulings, incorporated into Gratian’s Decretum (the foundational text of canon law), state that marriages are valid once the parties reach these minimum ages.19

This legal framework was not an aberration but represented the settled law of the Catholic Church, binding across Western Christendom. Thomas Aquinas (1225 – 1274 CE), the preeminent medieval theologian, affirmed in his Summa Theologica that the age of puberty determined marital capacity :

“The marriage of those who have not yet reached the age of puberty is invalid…But after puberty, they can contract marriage.“20

Crucially, Aquinas specified that this threshold was established by “the onset of puberty,” not a fixed chronological age, meaning that individual variation was recognized. A girl who menstruated at age eleven could validly marry ; the biological event, not the number, determined readiness.

Protestant Reformers and English Common Law

The Protestant Reformation, despite its theological break from Rome, largely retained traditional marriage ages. Martin Luther (1483 – 1546), in his writings on marriage, affirmed that girls could marry at twelve and boys at fourteen, stating :

“A girl begins to be a woman at twelve years… a boy begins to be a man at fourteen years.“21

Luther himself married Katharina von Bora when she was twenty-six and he was forty-two — an adult marriage by any standard — but his theological and legal writings confirm continuity with Catholic canon law regarding minimum ages.

John Calvin (1509 – 1564) similarly recognized twelve as the threshold for female marital capacity, writing in his Institutes of the Christian Religion that marriage was permissible upon reaching “the age of puberty, which in the case of women is twelve years.“22

English Common Law, shaped by both Catholic canon law and later Protestant modifications, retained the Roman-canonical ages. Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England (1765) states :

“The age of consent for marriage is fourteen in males and twelve in females.“23

This legal standard persisted in England until the 19th century and was exported to British colonies, including America, where similar ages governed marriage law well into the 1800s.

Documented Christian Marriages of Young Girls

Historical records document numerous Christian marriages involving girls aged twelve or younger, many celebrated within royal and noble families whose conduct shaped Christian cultural norms :

- Eleanor of England (1161 – 1214 CE), daughter of Eleanor of Aquitaine, was married to King Alfonso VIII of Castile in 1170 when she was approximately nine years old. Alfonso was about fifteen. The marriage was consummated several years later, but the contract was legally binding from age nine.24

- Isabella of Valois (1389 – 1409), daughter of King Charles VI of France, was married to King Richard II of England in 1396 when she was six years old. Richard was twenty-nine. Although consummation was delayed, the marriage was politically and legally recognized.25

- St. Elizabeth of Hungary (1207 – 1231), a revered Catholic saint, was betrothed at age four and married at fourteen to Ludwig IV of Thuringia (aged twenty-one). Her marriage is commemorated in Christian devotional literature as exemplary.

- Margaret Beaufort (1443 – 1509), mother of King Henry VII of England, was married to Edmund Tudor in 1455 when she was twelve years old. She gave birth to Henry VII at age thirteen, an event that nearly killed her due to the physical dangers of childbirth at such a young age. Despite the evident medical risks, the marriage was canonically valid and celebrated within Christian aristocratic society.26

These examples are not marginal aberrations but represent mainstream Christian practice among the most visible and religiously observant segments of society.

The Modern Shift in Christian Marriage Norms

Significant changes to Christian marriage law occurred only in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, driven not by theological revision but by social reform movements, industrialization, compulsory education, and evolving concepts of childhood.

The Age of Marriage Act 1929 in England raised the minimum age to sixteen for both sexes, representing a dramatic departure from centuries of Christian legal tradition.27 Similar legislative changes occurred across Europe and North America during the same period, reflecting shifts in economic structures (children remaining in school longer) and new psychological theories about adolescent development.

Importantly, these legal reforms were secular legislative acts, not theological reinterpretations. The Catholic Church did not formally raise the canonical minimum age from twelve to fourteen (and eventually sixteen) until the 1917 Code of Canon Law, and this change was explicitly acknowledged as a departure from traditional practice rather than a recovery of original Christian teaching.28

Theological Consistency and Polemical Hypocrisy

Christian critics who invoke ʿĀʾishah’s marriage as evidence of Islamic moral inferiority face an insurmountable consistency problem :

- Sacred Tradition : Christian sacred texts and venerated traditions affirm that Mary, the mother of God, was betrothed at twelve to an elderly man — a union regarded as divinely ordained.

- Canon Law : For over a millennium, the Catholic Church legally sanctioned marriage at age twelve for girls, treating such unions as valid sacraments.

- Historical Practice : Christian monarchs, nobles, and saints contracted marriages involving girls aged six to fourteen, with these unions celebrated, not condemned, by Christian authorities.

- Theological Authorities : Aquinas, Luther, Calvin, and other foundational Christian thinkers affirmed puberty-based marriage as morally and theologically legitimate.

If these Christian practices were moral in their historical contexts — or if modern Christians excuse them as products of their time — then intellectual honesty demands extending the same historical contextual grace to the Prophet Muḥammad. Conversely, if ʿĀʾishah’s marriage is condemned as inherently immoral regardless of context, then Christian sacred tradition, canon law, and historical practice must face identical condemnation.

Polemicists cannot coherently maintain that Mary’s betrothal at twelve was divinely blessed but ʿĀʾishah’s marriage at nine was depraved, that Eleanor of England’s marriage at nine was a neutral historical fact but ʿĀʾishah’s was criminal, or that Catholic canon law permitting marriage at twelve for a millennium was contextually understandable but Islamic jurisprudence applying similar standards was uniquely barbaric.

Such argumentation reveals not principled moral reasoning but polemical opportunism — a willingness to deploy standards against Islam that Christianity’s own historical record cannot survive.

Global Historical Precedents

Historical records indicate that early marriage occurred across civilisations long before the twentieth century. Marriage patterns across civilizations demonstrate this was a universal norm rather than a distinctively Islamic practice :

- Ankhesenamun (aged about 16) was married to her half-brother Tutankhamun (aged about 10) in c. 1332 BCE.

- Judith of Flanders (aged about 12 or 13) was married to Æthelwulf, King of Wessex (aged about 61), in October 856 CE.

- Eadgifu of Wessex (aged 16 or 17) was married to Charles the Simple, King of West Francia (aged about 40), in 919 CE.

- Isabella of Jerusalem (aged 10 or 11) married Humphrey IV of Toron (aged about 17) in 1183. They had been betrothed when Isabella was 8 years old.

- Mrinalini Devi (aged between 9 and 11) married Rabindranath Tagore (aged 22) in 1883.

- Liu Chi-chun (aged 16) married Yen Chia-kan (aged 19) in 1924.

The evidence demonstrates that early post-pubertal marriage was not distinctively Islamic but represented a shared norm across Jewish, Christian, and Islamic civilizations for most of recorded history.

Marriage in An Islamic Framework

Islamic Teachings on Puberty and Adulthood

Islam clearly teaches that adulthood starts when a person has attained puberty. From the collection of Bukhari, we read the following tracts :

“The boy attaining the age of puberty and the validity of their witness and the Statement of Allah : ‘And when the children among you attain the age of puberty, then let them also ask for permission (to enter).’ (Qur’an, 24:59)“29

“Al Mughira said, ‘I attained puberty at the age of twelve.’ The attaining of puberty by women is with the start of menses, as is referred to by the Statement of Allah : ‘Such of your women as have passed the age of monthly courses, for them prescribed period if you have any doubts (about their periods) is three months…’ [Qur’an, 65:4]“30

We also read from the same source :

“Al-Hasan bin Salih said, ‘I saw a neighbour of mine who became a grandmother at the age of twenty-one.’ The note for this reference says : ‘This woman attained puberty at the age of nine and married to give birth to a daughter at ten ; the daughter had the same experience.’ ”31

Reports preserved in classical collections describe cases in which women became mothers shortly after reaching puberty, illustrating that early biological maturity was neither rare nor socially condemned.

Legal Safeguards : Consent and the Option of Puberty

Islamic jurisprudence developed sophisticated protections for female consent and welfare. The Qurʾān prohibits forced marriage, stating :

“O you who believe, it is not lawful for you to inherit women by force.” (Qurʾān 4:19)

The Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ reinforced this principle in numerous hadith narrations, explicitly condemning marriages contracted without the bride’s consent. Among the most significant is the report :

“A previously married woman has more right concerning herself than her guardian, and a virgin’s permission must be asked, and her permission is her silence.“32

This hadith establishes two critical principles :

- Adult women : A previously married woman (thayyib) — understood as a mature, experienced woman — possesses autonomy in marriage decisions superior to her guardian’s authority. She must give explicit verbal consent, and the marriage is invalid without it.

- Virgin brides : A virgin’s consent is required, though it may be expressed through silence or non-objection rather than explicit verbal affirmation. This accommodation recognizes cultural norms regarding modesty but does not eliminate the consent requirement.

Classical jurists debated the precise parameters of this consent, particularly regarding young brides. The Ḥanafī school, following Imām Abū Ḥanīfah (d. 767 CE), held that even a virgin’s father could not compel her into marriage against her will once she reached puberty. If she objected — even silently through signs of distress — the marriage was voidable.

Most significantly, Islamic law established khiyār al-bulūgh (the option of puberty) — granting girls married before reaching puberty the right to annul the marriage upon reaching maturity if she objects to it.

The foundational hadith for this principle is narrated by ʿĀʾishah herself :

“A girl came to the Prophet ﷺ and said, ‘My father married me to his nephew to raise his social standing, and I did not want this.’ The Prophet ﷺ gave her the choice. She said, ‘I have accepted what my father did, but I wanted to establish that women have a say in this matter.’ ”33

This narration establishes that even when a father contracts a marriage on his daughter’s behalf, she retains the authority to ratify or reject it upon reaching maturity. The girl’s statement — “I wanted to establish that women have a say” — reflects an understanding that female agency, not paternal absolutism, governs marital validity.

The Ḥanafī school extended khiyār al-bulūgh most broadly. According to Ḥanafī jurists, a girl married by her father or guardian before puberty may annul the marriage immediately upon reaching puberty if she objects. The annulment is effected by her declaration (iqrār) before witnesses ; no judicial intervention is required. The marriage is retroactively dissolved, meaning she is not considered to have been validly married, protecting her from any social stigma.

Beyond consent mechanisms, Islamic jurisprudence established protections against premature consummation that could cause physical harm. The Ḥanafī school required that the bride be physically capable of intercourse without injury (tuṭīq al-waṭʾ). As previously noted, Imām al-Kāsānī emphasized that the criterion was the bride’s physical capacity to endure intercourse without suffering harm.

The Mālikī school articulated similar protections. Ibn Rushd explains that jurists agreed if intercourse would harm the wife, it is not permissible for the husband to have relations with her until the cause of harm is removed. Mālikī jurists defined “harm” (ḍarar) broadly, including not only immediate physical injury but also psychological distress or health risks.

These legal doctrines reflect an awareness that chronological age alone does not determine readiness for sexual relations. By requiring physical capacity and prohibiting harm, Islamic jurisprudence established a standard calibrated to individual biology rather than arbitrary numerical thresholds.

The marriage of the Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ to ʿĀʾishah must be understood within this legal and ethical framework. Several features of the marriage align with the protective mechanisms Islamic law would later systematize :

- Parental involvement : The marriage was arranged by ʿĀʾishah’s father, Abū Bakr, the Prophet’s closest Companion and a man of exemplary character. There is no indication of coercion or exploitation ; rather, Abū Bakr regarded the union as honorable and beneficial.

- Delayed consummation : The marriage contract was concluded when ʿĀʾishah was six, but consummation occurred at nine, following her menarche. This interval reflects the principle that consummation should await physical readiness, not proceed immediately upon legal marriage.

- Community oversight : The consummation was attended by women of the Anṣār (the Medinan Muslims), who prepared ʿĀʾishah and ensured the transition was conducted with dignity and care. This communal involvement provided social accountability and support.

- No evidence of harm : Neither physical injury nor psychological trauma is recorded. On the contrary, ʿĀʾishah’s post-marriage life exhibits confidence, intellectual vitality, and social authority — outcomes inconsistent with abuse.

Evidence from ʿĀʾishah’s Life and Agency

Beyond the absence of contemporary criticism and the legal framework protecting consent, the most compelling evidence regarding the marriage comes from ʿĀʾishah herself. Her own reflections, preserved across the hadith corpus, and her subsequent life trajectory provide direct testimony regarding her experience and agency within the marriage.

ʿĀʾishah as Hadith Scholar and Legal Authority

ʿĀʾishah bint Abī Bakr emerged as one of the most prolific transmitters of hadith in early Islam, with classical collections attributing over 2,210 narrations to her. Her authority extended across jurisprudence, Qurʾānic exegesis, and matters of ritual practice. She is counted among the mujtahidūn—those qualified to exercise independent legal reasoning — and male Companions, including ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb and ʿAbdullāh ibn ʿAbbās, consulted her on complex legal questions.

Abū Mūsā al-Ashʿarī, a senior Companion, stated :

“Whenever we encountered difficulty regarding a hadith, we asked ʿĀʾishah and found knowledge with her.“34

Her students included prominent scholars such as ʿUrwah ibn al-Zubayr, al-Qāsim ibn Muḥammad, and ʿAṭāʾ ibn Abī Rabāḥ, who transmitted not only legal rulings but also her corrections of other Companions’ interpretations.

Critically, ʿĀʾishah did not hesitate to challenge or correct male authorities when she believed them mistaken. She disputed legal positions attributed to Abū Hurayrah, Ibn ʿUmar, and others, providing alternative narrations or contextual clarifications. This intellectual assertiveness, documented across classical sources, indicates a personality characterized by confidence and authority rather than deference born of trauma or subjugation.

Political Leadership and the Battle of the Camel

ʿĀʾishah’s political activity after the Prophet’s death further demonstrates her public agency. Following the assassination of the third caliph, ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān, she became a central figure in the first Islamic civil war (fitna). She led an armed coalition demanding justice for ʿUthmān’s murder and opposing certain policies of ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib, the fourth caliph.

The Battle of the Camel (656 CE), named for ʿĀʾishah’s presence on a camel during the conflict, represents one of the most significant political events of early Islam. While later scholars debated the propriety of her involvement, none questioned her capacity for independent political judgment. Her leadership required logistical coördination, alliance-building, and military strategy — activities incompatible with the profile of someone psychologically damaged by childhood abuse.

Though defeated militarily and subsequently expressing regret over the conflict, ʿĀʾishah’s willingness to engage in high-stakes political contestation reveals a figure who exercised considerable autonomy and commanded substantial loyalty from segments of the Muslim community.

Her Own Reflections on Marriage to the Prophet

The hadith corpus preserves numerous narrations in which ʿĀʾishah herself reflects on her marriage. These accounts, transmitted decades after the Prophet’s death, consistently portray affection, respect, and cherished memories rather than resentment or criticism.

She narrates intimate details of domestic life — the Prophet’s kindness, his consultation with her on matters of revelation, his gentleness during her menstruation, and his final moments when he died resting against her chest. In Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, she describes the Prophet’s concern during her illness and his request to spend his final days in her apartment.35 Far from depicting constraint or coercion, these narrations convey emotional intimacy and mutual regard.

When ʿĀʾishah narrates the story of her marriage and consummation — including the detail about being taken from the swing by her mother — she does so without evident distress or critique. Her tone is matter-of-fact, situating the event within normal social practice. Had she perceived the marriage as abusive or improper, her later position as a respected authority would have afforded ample opportunity to reframe or criticize the arrangement, yet no such critique appears in the sources.

Evidence Against Trauma

Modern psychological frameworks identify specific behavioral patterns associated with childhood sexual abuse : difficulty trusting others, impaired intimate relationships, chronic fear or anxiety, diminished self-worth, and avoidance of trauma-related stimuli. ʿĀʾishah’s documented behavior exhibits none of these markers.

She maintained deep friendships, engaged confidently in public debate, assumed positions of leadership requiring social trust, and expressed clear opinions on controversial matters. Her willingness to preserve and transmit detailed accounts of her marital life, including intimate aspects of the Prophet’s domestic behavior, contradicts the avoidance patterns typical of trauma survivors.

While critics might argue that cultural conditioning could suppress expressions of harm, this explanation fails to account for ʿĀʾishah’s demonstrated willingness to challenge authority, correct powerful men, and involve herself in contentious political disputes. A personality capable of leading an army against a sitting caliph would presumably have been capable of articulating grievance regarding personal mistreatment, particularly in a religious tradition that valorized her status as “the Beloved of the Beloved.”

The Prophet’s Broader Marital Pattern

ʿĀʾishah’s experience must also be situated within the broader pattern of the Prophet’s conduct toward women. His marriages, aside from ʿĀʾishah, were to adult women, most of whom were widows or divorcees. Khadījah, his first wife, was approximately fifteen years his senior. Sawdah, Ḥafṣah, Umm Salamah, Zaynab bint Jaḥsh, and others were mature women with prior marital experience.

This marital pattern contradicts clinical definitions of pedophilia, which require a persistent and exclusive sexual attraction to prepubescent children. The Prophet’s overwhelming preference for adult partners, combined with the singular nature of his marriage to ʿĀʾishah at a young age, suggests a socially motivated alliance rather than deviant sexual preference.

Additionally, ḥadīth literature documents the Prophet’s general conduct toward women : his prohibition of domestic violence, his insistence on women’s consent in marriage (even when culturally fathers could compel), his encouragement of female education, and his respectful treatment of wives. ʿĀʾishah herself narrated :

“He never struck a servant or a woman.“36

The totality of evidence regarding ʿĀʾishah’s post-marriage life presents a figure of formidable intellect, political courage, and social authority. Her scholarly contributions shaped Islamic jurisprudence for centuries. Her political interventions influenced the course of early Islamic history. Her personal reflections convey affection and respect for the Prophet rather than resentment or trauma.

While modern audiences may find early marriage culturally jarring, the burden of evidence for alleging abuse requires demonstrating harm to the individual in question. In ʿĀʾishah’s case, the evidence points decisively in the opposite direction. Her life and legacy contradict the profile of a victim and instead reveal a woman who exercised agency, commanded respect, and shaped the intellectual and political landscape of early Islam.

Responding to Modern Critiques

The Fallacy of Presentism

Presentism refers to the methodological error of interpreting past societies exclusively through contemporary moral categories and then condemning historical actors for failing to conform to modern sensibilities. Historians widely regard presentism as a distortion that replaces historical explanation with moral projection, collapsing temporal distance and erasing the normative frameworks within which historical agents actually operated 37.

The moral vocabulary of the modern West is shaped by institutions and social structures that did not exist in seventh-century Arabia : universal mass schooling, a prolonged adolescence structured around formal education, bureaucratic age-of-consent regimes, modern state policing, forensic psychology, and highly standardised legal thresholds defining childhood and adulthood. These institutions fundamentally reshape expectations regarding maturity, responsibility, sexuality, and social agency 38. Treating them as timeless moral baselines imposes an anachronistic evaluative framework onto societies governed by radically different legal, biological, and cultural assumptions 39.

A historically responsible approach reconstructs the normative structures governing a society and evaluates conduct according to those internal standards. This requires asking how contemporaries understood concepts such as adulthood, consent, family duty, sexual propriety, and social honour, and whether actions were perceived within that culture as coercive, harmful, scandalous, or deviant. 40 Moral evaluation, in this framework, proceeds not by retroactive condemnation but by examining whether historical actors violated the ethical expectations of their own communities.41

In cases involving premodern marriage norms, historians, anthropologists, and legal scholars consistently warn against projecting modern Western age categories onto societies whose definitions of maturity were anchored in puberty, economic responsibility, kinship obligations, and communal reputation rather than state-regulated chronological thresholds 42. Ethical critique remains possible, but only when grounded in historically intelligible standards rather than contemporary ideological reflexes 43.

Clinical Definitions vs. Cultural Practices

A central component of polemical criticism involves the accusation of pedophilia — a term with specific clinical meaning that is frequently misapplied in historical contexts. Precision in terminology is essential for distinguishing between psychiatric disorder and culturally variable marriage practices.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‑5), published by the American Psychiatric Association, defines pedophilic disorder as :

“Over a period of at least 6 months, recurrent, intense sexually arousing fantasies, sexual urges, or behaviors involving sexual activity with a prepubescent child or children (generally age 13 years or younger).“44

The diagnosis requires that :

- The individual has acted on these urges, or the urges cause marked distress or interpersonal difficulty.

- The individual is at least 16 years old and at least 5 years older than the child.

- The attraction is recurrent and constitutes a predominant or exclusive sexual interest.

Critically, pedophilia as a clinical diagnosis refers to attraction to prepubescent children—those who have not yet undergone puberty. The DSM explicitly distinguishes pedophilia from other patterns of attraction, including those involving postpubescent minors.

ʿĀʾishah, according to the hadith sources under consideration, had reached menarche — a biological marker of puberty — before consummation at age nine. While modern medicine recognizes that menarche represents the beginning rather than completion of pubertal development, it nonetheless marks a transition beyond the prepubescent state. Thus, even accepting the traditional age narrations, the relationship does not meet the clinical threshold for pedophilia.

Equally significant is the requirement that pedophilic disorder involve a persistent and predominant attraction to prepubescent children. The Prophet Muḥammad’s marital history demonstrates the opposite pattern. His first marriage was to Khadījah bint Khuwaylid, who was approximately 40 years old at the time (with the Prophet around 25), making her about 15 years his senior. They remained in an exclusive monogamous marriage for approximately 25 years until her death.

After Khadījah, his marriages were overwhelmingly to adult women : Sawdah bint Zamʿah (a widow, estimated to be in her mid-to-late 50s), Ḥafṣah bint ʿUmar (a widow in her early 20s), Zaynab bint Khuzaymah (a widow, approximately 30 years old), Umm Salamah (a widow, approximately 29 years old), Zaynab bint Jaḥsh (a divorcee, approximately 35 – 38 years old), and others. Of his documented marriages and relationships, only ʿĀʾishah is reported to have married before physical maturity, with consummation occurring shortly after puberty.

This singular case within a broader pattern of exclusive relationships with adult women — many significantly older — contradicts the diagnostic criteria for pedophilic disorder, which require persistent attraction to prepubescent children as a dominant sexual preference.

Modern safeguarding frameworks rightly classify sexual contact with prepubescent children as inherently abusive regardless of cultural context, recognizing the profound developmental, physical, and psychological harms such contact causes. However, the category of “child marriage” in historical scholarship encompasses a wider range of practices, including marriages involving postpubescent adolescents that occurred within normative social structures.

Child protection specialists distinguish between :

- Marriage involving prepubescent children with immediate sexual contact : Universally recognized as harmful across cultures and time periods, associated with severe physical injury, psychological trauma, and violations of bodily integrity.

- Betrothal or marriage contracts involving prepubescent children with delayed consummation : Common in premodern Europe, Asia, and the Middle East, where legal marriage established kinship alliances but cohabitation awaited physical maturity.

- Marriage involving early postpubescent adolescents : Historically normative across civilizations, governed by community oversight, kinship obligations, and cultural expectations of readiness.

The marriage of Aisha to the Prophet, involving a contract at age 6 and consummation at age 9 (following menarche), aligns with the second and third categories rather than the first. The multi-year interval between betrothal and consummation, the involvement of ʿĀʾishah’s parents, the community oversight, and the social norms governing such unions distinguish this from cases of predatory abuse driven by paraphilic attraction.

Contemporary ethical frameworks rightly prioritize the prevention of harm, particularly to vulnerable populations. Assessments of harm, however, require attention to the individual’s actual experience, social context, and long-term outcomes rather than abstract categorical judgments.

In ʿĀʾishah’s case : no evidence of physical harm exists in the sources ; no evidence of psychological harm appears (her subsequent life demonstrates confidence, authority, intellectual achievement, and political agency — outcomes inconsistent with severe developmental trauma); no evidence of social stigma is recorded (she was honored within her community as “the Mother of the Believers,” a title of respect maintained throughout her life); and no evidence of personal regret surfaces (her own narrations, transmitted decades later, convey affection and pride in her relationship with the Prophet).

This analysis does not endorse child marriage in contemporary contexts, where extended education, delayed economic independence, and developmental psychology have fundamentally altered understandings of childhood and maturity. Modern international consensus rightly establishes 18 as a minimum marriage age, recognizing that cognitive, emotional, and social development continues well into the late teens.

The ethical question, however, is not whether seventh-century practices align with twenty-first-century norms, but whether historical actors violated the ethical frameworks of their own societies or caused recognizable harm to those involved. Pedophilia, as a clinical category, describes a paraphilic disorder — an abnormal, recurrent, and exclusive sexual attraction to prepubescent children that operates outside cultural norms and causes harm.

The marriage of the Prophet Muḥammad to ʿĀʾishah, occurring within a society that recognized puberty as the threshold of adulthood, involving community oversight and parental involvement, resulting in no documented harm, and representing an isolated case within a broader pattern of marriages to adult women, does not meet this clinical standard.

Absence of Contemporary Objections

No historical record indicates objection to this marriage from Muslim, pagan, Jewish, Christian, or secular contemporaries. Given the intense opposition faced by the Prophet ﷺ from the Quraysh polytheists, Jewish tribes of Medina, and various political adversaries, the absence of recorded criticism strongly suggests that the marriage was not perceived as scandalous within Arabian society or broader regional norms.

The Prophet’s enemies were not reticent in their criticisms. They accused him of sorcery, madness, poetry, fabricating revelation, and political ambition. They mocked his teachings, opposed his mission militarily, and attempted character assassination through various means. Yet no contemporary source — hostile or sympathetic — records criticism of his marriage to ʿĀʾishah on grounds of her age.

Nabia Abbott observes that early Islamic historical sources contain no commentary expressing concern over the age disparity or youth of the bride, noting that ʿĀʾishah was depicted as playful rather than victimised :

In no version is there any comment made on the disparity of the ages between Mohammed and Aishah or on the tender age of the bride who, at the most, could not have been over ten years old and who was still much enamoured with her play.45

W. Montgomery Watt similarly concludes :

From the standpoint of Muhammad’s time, then, the allegations of treachery and sensuality cannot be maintained. His contemporaries did not find him morally defective in any way. On the contrary, some of the acts criticized by the modern Westerner show that Muhammad’s standards were higher than those of his time.46

Aside from the fact that no one was displeased with him or his actions, he was a paramount example of moral character in his society and time. To judge the Prophet’s morality by modern cultural standards rather than those of his historical context is, therefore, methodologically flawed. Contemporary silence, combined with ʿĀʾishah’s later prominence and the marriage’s conformity to legal and social norms, indicates it was regarded as honorable rather than deviant.

Conclusions

This study has demonstrated that the marriage of the Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ to ʿĀʾishah bint Abī Bakr, when examined through textual, historical, anthropological, medical, legal, and comparative frameworks, emerges as consistent with normative practices of seventh-century Arabian society and broader Semitic civilization.

The marriage involved parental consent by Abū Bakr (her father and the Prophet’s closest Companion), a three-year delay between contract and consummation pending physical maturity, community oversight by women of the Anṣār who prepared ʿĀʾishah, and legal protections ensuring female agency through mechanisms such as khiyār al-bulūgh (the option of puberty). ʿĀʾishah’s own testimony, preserved across the hadith corpus, conveys affection and respect rather than trauma or resentment. Her subsequent life as a prolific hadith scholar, jurist, teacher, and political leader contradicts allegations of abuse. No contemporary source — Muslim, pagan, Jewish, or Christian — recorded objection to the marriage, suggesting it operated within accepted social boundaries.

Comparative analysis reveals that Jewish legal tradition discussed marriages at even younger ages (as reflected in Talmudic sources regarding marriage at three years), while Christian civilization institutionalized functionally identical practices through canon law (marriage at twelve for girls), royal custom, and theological teaching for over a millennium. The Virgin Mary’s betrothal at twelve to elderly Joseph, medieval canon law’s validation of marriage at that age, documented Christian marriages involving girls as young as six (such as Isabella of Valois), and the affirmation of these practices by authorities including Thomas Aquinas, Martin Luther, and John Calvin demonstrate that early post-pubertal marriage was not distinctively Islamic but represented shared Semitic and Mediterranean norms.

Critics who condemn the marriage of Aisha while excusing parallel Christian practices engage in polemical opportunism rather than principled moral reasoning. If Mary’s betrothal at twelve was divinely blessed, if Catholic canon law sanctioning marriage at twelve for over a millennium was contextually understandable, and if Christian royal marriages at similar ages are historically defensible, then intellectual consistency demands extending identical historical grace to the Prophet Muḥammad.

Modern polemics persist in framing the marriage as immoral by imposing contemporary standards onto radically different historical contexts. Such arguments commit the fallacy of presentism — evaluating seventh-century Arabia by twenty-first-century Western norms shaped by institutions (mass schooling, prolonged adolescence, bureaucratic age-of-consent regimes, forensic psychology) that did not exist in premodern societies. They also misapply clinical terminology : pedophilia, as defined by the DSM‑5, requires persistent, exclusive attraction to prepubescent children. ʿĀʾishah had reached menarche (marking puberty) before consummation, and the Prophet’s overwhelming pattern of marriages to adult women (including his first wife Khadījah, fifteen years his senior) contradicts the diagnostic criteria for pedophilic disorder.

These critiques ignore the Prophet’s broader ethical legacy, including reforms that elevated women’s status and condemned female infanticide. Pre-Islamic Arabia regarded female birth as shameful, leading in some cases to infanticide. The Qurʾān condemns this practice :

“And when the news of [the birth of] a female [child] is brought to one of them, his face becomes dark, and he suppresses grief. He hides himself from the people because of the ill of which he has been informed. Should he keep it in humiliation or bury it in the ground ? Unquestionably, evil is what they decide.“47

The Qurʾān warns that buried infant girls will be questioned on the Day of Judgment :

“And when the girl [who was] buried alive is asked for what sin she was killed.“48

The Prophet ﷺ reinforced these teachings by encouraging compassion toward daughters and promising spiritual reward for their care. Reports transmitted by Abū Saʿīd al-Khudrī and Ibn ʿAbbās record :

“Whoever raises two daughters until they reach maturity, he and I will come on the Day of Resurrection like this” — and he joined his fingers.49

Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim further preserves :

“ ‘Whoever takes care of two girls until they reach puberty, he and I will come on the Day of Resurrection like this’ — and he interlaced his fingers.“50

Such teachings undermine claims that the Prophet ﷺ harboured abusive attitudes toward girls or women. On the contrary, his mission emphasised the protection of women and orphans, encapsulated in his reported declaration :

“I declare inviolable the rights of the two vulnerable ones : the orphan and the woman.“51

Historical evidence indicates marriage at or shortly after puberty was normative across civilizations for most of recorded history. Evaluating the Prophet’s marriage to ʿĀʾishah requires historical contextualization, not anachronistic moral projection. The marriage operated within a coherent ethical and social framework — one that recognized puberty as the threshold of adulthood, required parental involvement and community oversight, delayed consummation pending physical readiness, provided legal mechanisms protecting female consent (khiyār al-bulūgh), and resulted in no documented harm to the bride.

Modern moral revolutions — driven by industrialization, mass education, psychological research, and evolving concepts of childhood — have reshaped Western marriage norms in ways that would have been incomprehensible to societies in the medieval, Reformation, or even Victorian periods. These changes reflect social progress, but they do not render previous generations morally monstrous, nor do they provide grounds for condemning parallel practices in other civilizations while excusing identical practices within one’s own tradition.

Historically informed critique must apply consistent standards. Those who condemn the marriage of Aisha to the Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ must either condemn Mary’s betrothal to Joseph, Christian canon law’s millennium-long sanction of marriage at twelve, the marriages of Eleanor of England and Margaret Beaufort, and the theological affirmations of Aquinas, Luther, and Calvin — or acknowledge that early post-pubertal marriage was a shared civilizational norm that cannot be uniquely attributed to Islam as evidence of moral deficiency.

The evidence presented in this study supports the conclusion that the marriage of the Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ to ʿĀʾishah bint Abī Bakr was consistent with the accepted social, legal, and moral norms of its time ; involved protective mechanisms ensuring consent and welfare ; resulted in no documented harm ; and cannot reasonably be construed as sexual predation, pedophilia, or child abuse under either historical or clinical definitions. Rather than revealing moral deviance, the marriage reflects a coherent ethical framework that modern polemics often misunderstand or deliberately distort.

FAQs : Age of Aisha at Marriage with Muhammad

What was the age of Aisha at marriage with Muhammad according to hadith ?

Hadith in Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī and Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim report betrothal at six and consummation at nine. Scholars analyze these narrations within broader historical and legal contexts.

What was the age of Aisha at marriage to Prophet Muhammad in historical terms ?

The historical age of Aisha at marriage with Muhammad aligns with seventh-century norms, where puberty — not modern numerical age — determined adulthood.

Does the Aisha age of marriage in hadith imply abuse or immorality ?

There is no historical evidence indicating abuse. Moral judgments based on modern norms risk presentism, an anachronistic interpretive error.

Was the age of Aisha at the time of marriage unusual for that era ?

No. Early post-pubertal marriage was common across Semitic, medieval Christian, Greco-Roman, and Asian societies.

Did anyone in the Prophet’s time object to the marriage ?

There are no surviving records — Muslim, secular, or otherwise — showing objections framed as moral outrage at the Prophet’s marriage to Aisha at the time.

Is calling this “pedophilia” academically meaningful ?

As a clinical diagnosis, “pedophilic disorder” refers to recurring, intense sexual interest in prepubescent children and is defined in modern diagnostic/clinical frameworks. Historians cannot diagnose the past, and polemical use of the term typically collapses multiple distinct categories (law, puberty, harm evidence, diagnosis) into a slogan.

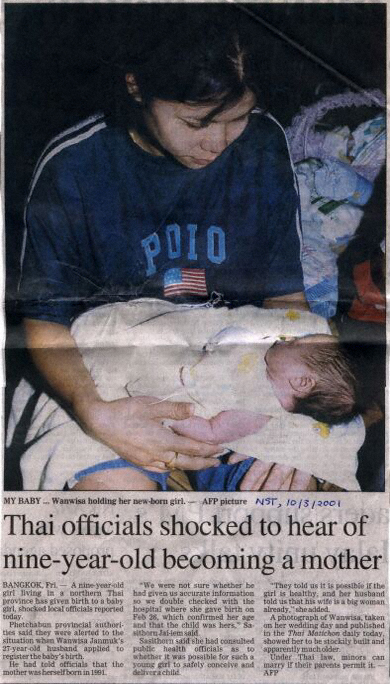

Appendix : A Married Nine-Year-Old In Thailand Gives Birth

Below is a news article from the New Straits Times, Malaysia, dated 10th March 2001about a nine-year old girl living in northern Thailand giving birth to a baby girl. The fact that a nine-year-old girl is mature enough to give birth proves the point above about girls reaching puberty earlier than men.

The original news report can be read here. Should the husband of this young girl be accused of “child molestation”, as insinuated by the Christian missionaries ?

Notes- Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, Kitāb al-Nikāḥ, ḥadīth 5134[⤶]

- Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, Kitāb al-Nikāḥ, ḥadīth 1422a[⤶]

The Incredible Machine, National Geographic Society, p. 235 [⤶]The Incredible Machine, National Geographic Society, p. 239 [⤶]- Ploss, Herman H., Max Bartels, and Paul Bartels, Woman : An Historical Gynaecological and Anthropological Compendium, vol. 1, Lord & Bransby, 1988, p. 563[⤶]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, “Adolescent Pregnancy, Contraception, and Sexual Activity,” ACOG Committee Opinion No. 699, May 2017, reaffirmed 2019[⤶]

- Al-Kāsānī, ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn Abū Bakr ibn Masʿūd, Badāʾiʿ al-Ṣanāʾiʿ fī Tartīb al-Sharāʾiʿ [The Marvels of Craftsmanship in Ordering the Laws], vol. 2, Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyyah, 1986, pp. 334 – 335[⤶]

- Ibn Rushd, Abū al-Walīd Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad, Bidāyat al-Mujtahid wa-Nihāyat al-Muqtaṣid [The Distinguished Jurist’s Primer], trans. Imran Ahsan Khan Nyazee, vol. 2, Garnet Publishing, 1996, pp. 13 – 14[⤶]

- West, Jim. Ancient Israelite Marriage Customs. Quartz Hill Journal of Theology (n.d.)[⤶]

- Arthen, Sue Curewitz, “Rites of Passage : Puberty,” EarthSpirit, accessed 25 Jan. 2026[⤶]

- Masters, R.E.L., and Allan Edwards, The Cradle of Erotica : A Study of Afro-Asian Sexual Expression and an Analysis of Erotic Freedom in Social Relationships, Julian Press, 1962, p. 94[⤶]

- Rabbi Tobiah ben Eliezer, Pesikta Zutrata (also known as Lekah Tov), Midrashic commentary on Genesis 24, compiled c. 11th century, Hebrew text with English translation in Midrash Lekach Tov, ed. Solomon Buber, Vilna, 1880[⤶]

- Babylonian Talmud, Sanhedrin 55b, trans. Soncino Press, ed. Rabbi Dr. I. Epstein, Soncino Press, 1935 – 1948[⤶]

- Babylonian Talmud, Sanhedrin 69a, trans. Soncino Press, ed. Rabbi Dr. I. Epstein, Soncino Press, 1935 – 1948[⤶]

- Caro, Joseph, Shulchan Arukh, Even HaEzer [Code of Jewish Law, Laws of Marriage], Section 20, 16th century, English trans. available at Sefaria, accessed 25 Jan. 2026[⤶]

- The Protevangelium of James, trans. Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson, Ante-Nicene Fathers, vol. 8, ed. Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe, Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1886, 8:2, pp. 363 – 364[⤶]

- The History of Joseph the Carpenter, trans. Alexander Walker, Ante-Nicene Fathers, vol. 8, ed. Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe, Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1886, 2:2, pp. 388 – 389[⤶]

- The Digest of Justinian, trans. Alan Watson, ed. Theodor Mommsen and Paul Krueger, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1985, 23.2.4, vol. 1, p. 665[⤶]

- Decretum Gratiani [Concordia discordantium canonum], compiled by Gratian, c. 1140, ed. Emil Friedberg, Corpus Iuris Canonici, vol. 1, Bernhard Tauchnitz, 1879[⤶]

- Aquinas, Thomas, Summa Theologica, trans. Fathers of the English Dominican Province, Benziger Bros., 1947, Supplement, Question 58, Article 5[⤶]

- Luther, Martin, Luther’s Works, vol. 45, The Christian in Society II, ed. Walther I. Brandt, Fortress Press, 1962, p. 18[⤶]

- Calvin, John, Institutes of the Christian Religion, trans. Ford Lewis Battles, ed. John T. McNeill, Westminster John Knox Press, 1960, Book IV, Chapter 19, Section 37[⤶]

- Blackstone, William, Commentaries on the Laws of England, vol. 1, Book 1, Chapter 15, Clarendon Press, 1765, p. 436[⤶]

- Shadis, Miriam, “Berenguela of Castile’s Political Motherhood : The Management of Sexuality, Marriage, and Succession,” Medieval Mothering, ed. John Carmi Parsons and Bonnie Wheeler, Garland Publishing, 1996, pp. 335 – 358[⤶]

- Dunn-Lardeau, Brenda, ed., Legenda Aurea : Sept Siècles de Diffusion, Bellarmin, 1986, p. 156[⤶]

- Jones, Michael K., and Malcolm G. Underwood, The King’s Mother : Lady Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond and Derby, Cambridge University Press, 1992, pp. 35 – 40[⤶]

- Age of Marriage Act 1929, 19 & 20 Geo. 5, c. 36, UK Parliament, 1929[⤶]

- Codex Iuris Canonici [Code of Canon Law], promulgated by Pope Benedict XV, 27 May 1917, Canon 1067, English trans. Edward N. Peters, The 1917 or Pio-Benedictine Code of Canon Law, Ignatius Press, 2001[⤶]

- Al-Bukhari, Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, Volume 3, Book of Witnesses, Chapter 18, Dār Ṭawq al-Najāh, 1422 AH, p. 513[⤶]

- Al-Bukhari, Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, Volume 3, Book of Witnesses, Chapter 18, Dār Ṭawq al-Najāh, 1422 AH, p. 513[⤶]

- Al-Bukhari, Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, Volume 3, Book of Witnesses, Chapter 18, Dār Ṭawq al-Najāh, 1422 AH, p. 513[⤶]

- Muslim ibn al-Ḥajjāj, Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, Kitāb al-Nikāḥ [Book of Marriage], ḥadīth no. 1421, Dār al-Salām, 2007[⤶]

- Ibn Mājah, Muḥammad ibn Yazīd, Sunan Ibn Mājah, Kitāb al-Nikāḥ [Book of Marriage], ḥadīth no. 1873, Dār al-Salām, 2007[⤶]

- Al-Tirmidhī, Muḥammad ibn ʿĪsā, Sunan al-Tirmidhī, Kitāb al-Manāqib [Book of Virtues], ḥadīth no. 3883, Dār al-Gharb al-Islāmī, 1998[⤶]

- Al-Bukhārī, Muḥammad ibn Ismāʿīl, Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, Kitāb al-Nikāḥ [Book of Marriage], ḥadīth no. 4451, Dār Ṭawq al-Najāh, 1422 AH[⤶]

- Muslim ibn al-Ḥajjāj, Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, Kitāb al-Faḍāʾil [Book of Virtues], ḥadīth no. 2328, Dār al-Salām, 2007[⤶]

- Herbert Butterfield, The Whig Interpretation of History (London : G. Bell and Sons, 1931), pp. 5 – 7 ; David Hackett Fischer, Historians’ Fallacies : Toward a Logic of Historical Thought (New York : Harper & Row, 1970), pp. 135 – 144 ; Alex Walsham, “Past and Presentism,” Past & Present, no. 234 (2017): 213 – 233 ; Quentin Skinner, Visions of Politics, Vol. 1 : Regarding Method (Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 2002), pp. 57 – 62[⤶]

- Philippe Ariès, Centuries of Childhood : A Social History of Family Life (New York : Vintage, 1962), pp. 125 – 130 ; Hugh Cunningham, Children and Childhood in Western Society Since 1500 (London : Longman, 1995), pp. 54 – 61 ; Daniel Lord Smail, On Deep History and the Brain (Berkeley : University of California Press, 2008), pp. 89 – 95[⤶]

- George W. Stocking Jr., “On the Limits of Presentism and Historicism,” Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, vol. 1, no. 3 (1965): 211 – 218 ; Talal Asad, Formations of the Secular : Christianity, Islam, Modernity (Stanford : Stanford University Press, 2003), pp. 191 – 198[⤶]

- Quentin Skinner, Visions of Politics, Vol. 1 : Regarding Method (Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 2002), pp. 57 – 62 ; Peter Burke, What Is Cultural History ? (Cambridge : Polity Press, 2004), pp. 72 – 78 ; Marshall Sahlins, Culture and Practical Reason (Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 1976), pp. 67 – 73[⤶]

- David Hackett Fischer, Historians’ Fallacies : Toward a Logic of Historical Thought (New York : Harper & Row, 1970), pp. 136 – 144 ; Alex Walsham, “Past and Presentism,” Past & Present, no. 234 (2017): 214 – 218[⤶]

- Philippe Ariès, Centuries of Childhood : A Social History of Family Life (New York : Vintage, 1962), pp. 125 – 130 ; Judith Tucker, Women, Family, and Gender in Islamic Law (Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 2008), pp. 39 – 45 ; Hugh Cunningham, Children and Childhood in Western Society Since 1500 (London : Longman, 1995), pp. 54 – 61 ; Walter Scheidel, Ian Morris, and Richard Saller, eds., The Cambridge Economic History of the Greco-Roman World (Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 2007), pp. 112 – 118[⤶]

- George W. Stocking Jr., “On the Limits of Presentism and Historicism,” Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, vol. 1, no. 3 (1965): 211 – 218 ; Daniel Lord Smail, On Deep History and the Brain (Berkeley : University of California Press, 2008), pp. 89 – 95 ; Talal Asad, Formations of the Secular : Christianity, Islam, Modernity (Stanford : Stanford University Press, 2003), pp. 191 – 198[⤶]

- American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed., American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013, p. 697[⤶]

Nabia Abbott, Aishah, The Beloved of Mohammed, p. 7 [⤶]W. M. Watt, Muhammad : Prophet and Statesman, (Oxford University Press, 1961), p. 229 [⤶]- Qurʾān 16:58 – 59[⤶]

- Qurʾān 81:8 – 9[⤶]

- Abū Dāwūd, Sulaymān ibn al-Ashʿath, Sunan Abī Dāwūd, Dār al-Risālah al-ʿĀlamiyyah, 2009, Book of Manners (Kitāb al-Adab), ḥadīth no. 5147[⤶]

- Muslim ibn al-Ḥajjāj, Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, Dār al-Salām, 2007, Book of Kindness and Maintaining Ties (Kitāb al-Birr wa’l-Ṣilah), ḥadīth no. 2631[⤶]

- Ibn Mājah, Muḥammad ibn Yazīd, Sunan Ibn Mājah, Dār al-Salām, 2007, Kitāb al-Adab, ḥadīth no. 3678[⤶]