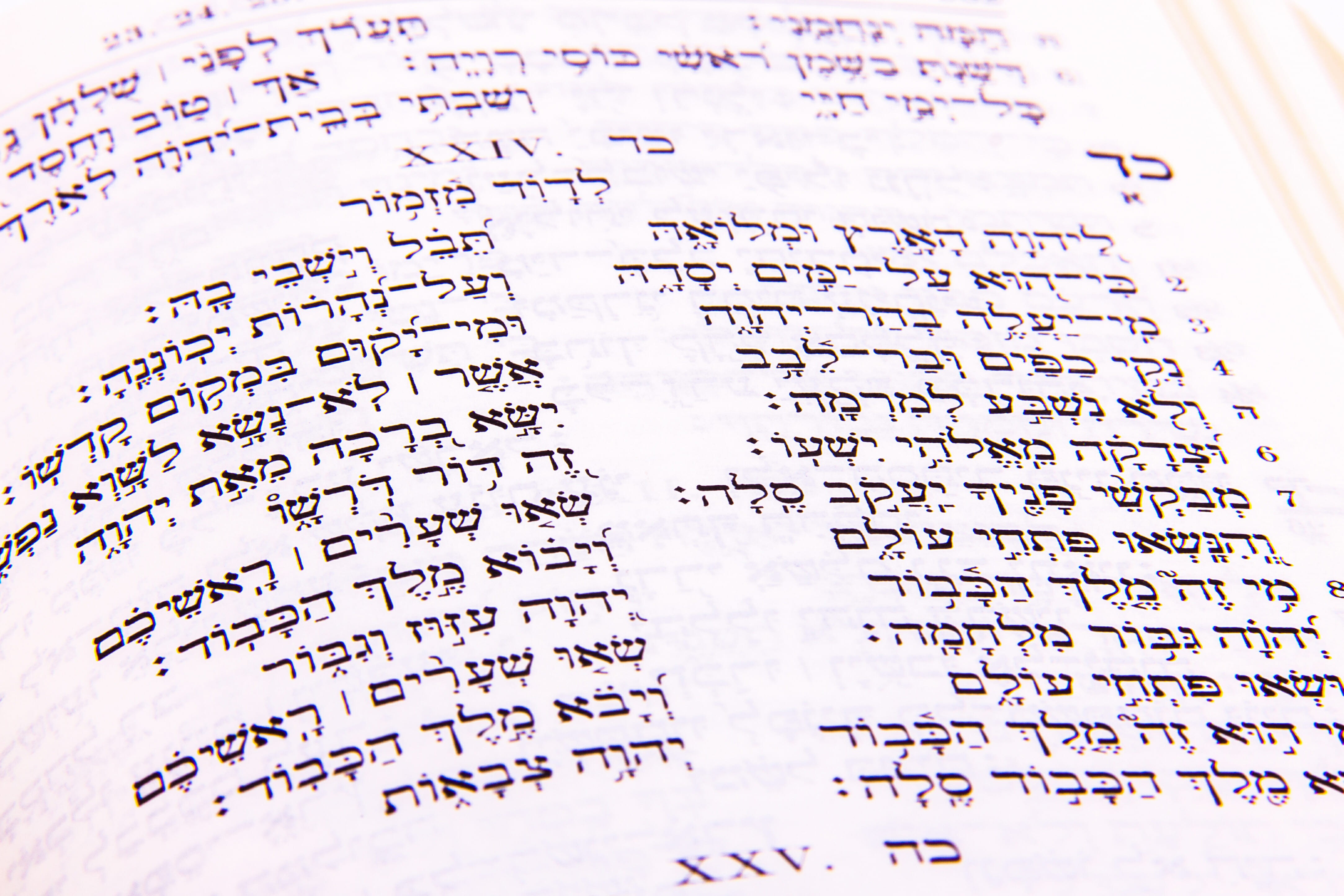

One of the recurring claims made by Christian missionaries is that Muslims worship a fundamentally different deity, often hinging on the assumption that the Islamic name for God, Allah ( ) has no linguistic or theological connection to the Judeo-Christian concept of God, commonly referred to as Yahweh or Elohim (

) has no linguistic or theological connection to the Judeo-Christian concept of God, commonly referred to as Yahweh or Elohim ( ). This claim, however, disintegrates under closer scrutiny, particularly when we examine the use of Elohim in the Hebrew Quran, which serves as compelling evidence of the shared monotheistic tradition across the Semitic faiths.

). This claim, however, disintegrates under closer scrutiny, particularly when we examine the use of Elohim in the Hebrew Quran, which serves as compelling evidence of the shared monotheistic tradition across the Semitic faiths.

Contrary to the polemical suggestion that Allāh is foreign to the biblical tradition, scholars widely accept that the root of Elohim in Arabic, namely ʾilāh, is indeed a cognate of ʾĕlōah in Hebrew. This linguistic relationship is not only theoretically valid — it is observable in actual scripture translations. In fact, historical Hebrew translations of the Qur’an demonstrate that Jewish translators consistently rendered the Arabic Allāh as ʾĔlōhīm. This consistency refutes the notion that the God of Islam is somehow unrelated to the God of the Hebrew Bible.

Connection Between Elohim and Allah

Linguistically, both Allah and Elohim originate from the shared Semitic triliteral root ʾ‑L-H (أ‑ل-ه in Arabic ; א‑ל-ה in Hebrew), conveying the concept of deity. W.E. Vine, Merrill F. Unger, and William White Jr. in their Complete Expository Dictionary affirm this link clearly :

[…]a cognate form of the word allah, the designation of deity used by the Arabs.1

This statement not only confirms the etymological connection but also undermines the missionary argument that Muslims and Jews do not share common linguistic ground in their conception of God. Understanding the parallel between Elohim and Allah offers a foundation for interfaith comprehension and exposes the flaws in accusatory missionary narratives. This cannot be better exemplified than to see it in a Hebrew translation of the Qur’an.

The first complete Hebrew translation of the Qur’an was undertaken by the German Jewish orientalist Hermann Reckendorf in 1857, titled Der Koran ins Hebräische Übertragen, published in Leipzig.2 Reckendorf’s work, though less known today, marked a pivotal moment in interfaith textual transmission — it represented one of the earliest systematic attempts by a European Jewish scholar to render the Islamic scripture into the sacred language of the Hebrew Bible. His motivations were both philological and theological, aimed at demonstrating the structural and conceptual parallels between Islam and Judaism by aligning Qur’anic vocabulary with established Hebrew religious terminology. This included rendering the Arabic Allāh as ʾĔlōhīm in the Hebrew Quran, mirroring the Hebrew Bible’s consistent nomenclature for the divine.

This pioneering effort was succeeded by several important Hebrew translations, each reflecting the intellectual and ideological climate of its time. Among them, Yōsēf Yōʾēl Rivlīn’s 1936 translation stands out as the most influential. A prominent Zionist scholar and orientalist, Rivlīn approached the Qur’an with a unique blend of scholarly rigor and cultural sensitivity. His translation, published by Devir in Tel Aviv, remains one of the most widely cited sources in comparative Semitic linguistics and religious studies. Rivlīn’s version is especially notable for its careful attention to theological fidelity — he frequently uses ʾĔlōhīm to render Allāh, thereby affirming the linguistic and conceptual unity between the Abrahamic faiths and maintaining the word ʾĔlōhīm in the Hebrew Quran.

Later contributions came from Aharōn ben Shemesh in 1971, who brought a modernist tone to the text, and Ūrī Rubin in 2005, whose academic translation was produced under the auspices of Tel Aviv University Press. Rubin, a well-respected scholar in Islamic studies and Arabic literature, based his work on critical editions of the Qur’anic text, rendering the Hebrew in a style intended for scholarly readership. Though more recent, Rubin’s version is typically used in academic circles rather than popular or interfaith discourse.

Among these translations, Rivlīn’s work continues to hold pre-eminence in terms of citation frequency and influence, particularly within interfaith studies and linguistic analyses. His choice of ʾĔlōhīm — as opposed to more generic Hebrew terms like ʾĒl or Hašēm — reflects a deliberate theological alignment that challenges polemical claims of discontinuity between Islam and the Hebrew tradition. In Rivlīn’s rendering, ʾĔlōhīm in the Hebrew Quran becomes not just a linguistic equivalent, but a theological affirmation of shared monotheism across Semitic revelation.

Examples of Elohim in the Hebrew Quran

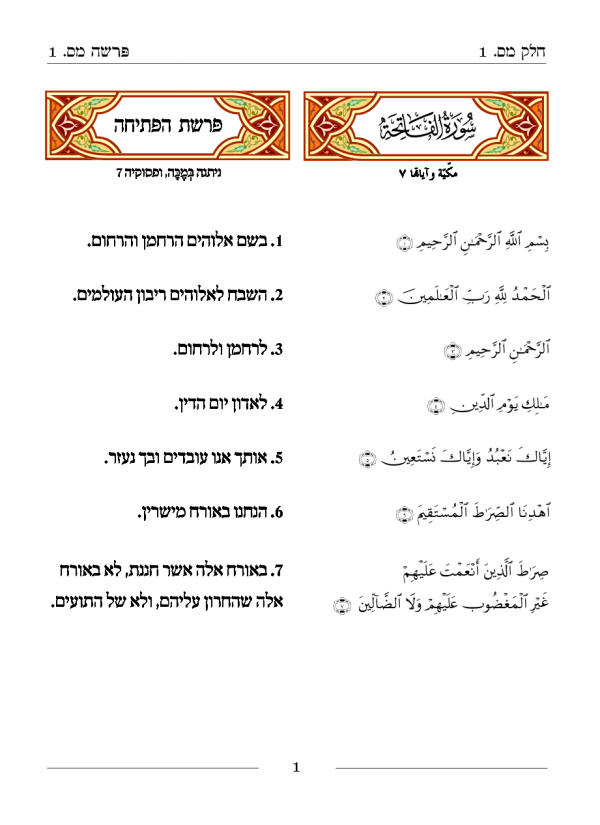

Here are select examples where Rivlin rendered the Arabic “Allah” as ʾĔlōhīm in the Hebrew Quran, affirming the theological unity expressed in the Qur’an :

Qur’an 1:1

This appears in Qur’an 1:1 (Sura’ al-Fatiha) of the Hebrew translation3 :

Bšēm ʾĔlōhīm ha-raḥamān wə-ha-raḥūm

Compare it with the very same verse in the Arabic Qur’an :

Bismi-llāhi al-Raḥmāni al-Raḥīm

Both translate into English as : “In the name of God, Most Gracious, Most Merciful.“4

Apart from the example given above, we would like to present more examples from the Hebrew translation of the Qur’an, which uses the word ʾĔlōhīm and Eloh. Note that the Hebrew translation always renders Ilah and Allah as Eloh and ʾĔlōhīm, respectively.

Qur’an 3:2

The following appears in Qur’an 3:2 of the Hebrew translation :

ʾĔlōhīm, ʾēn ʾĕlōah mibbalʿādāyw, ha-ḥay, ha-qayyām

The original Arabic rendering of Qur’an 3:2 is :

Allāhu lā ʾilāha ʾillā huwa al-ḥayy al-qayyūm

which translates into English as : “God ! There is no god but He, the Living, the Self-Subsisting, Eternal”.

Qur’an 3:18

The next image appears in Qur’an 3:18 of the Hebrew translation :

Heʿīd ʾĔlōhīm kî ʾēn ʾĕlōah mibbalʿādāyw, wə-ha-malʾāḵīm wə-ʾanšē ha-daʿat yaʿīdu kēn

The original Arabic rendering of Qur’an 3:18 would be :

Shahida Allāhu ʾannahū lā ʾilāha ʾillā huwa wa-l-malāʾikatu wa-ʾulū al-ʿilmi qāʾiman bi-l-qisṭi

This translates into English as : “There is no god but He : That is the witness of God, His angels, and those endued with knowledge, standing firm on justice. There is no god but He, The Exalted in Power, The Wise”.

Qur’an 6:1

This last example is from Qur’an, 6:1 of the Hebrew translation :

Ha-tehillāh lʾĔlōhīm, ʾăšer bārā ʾet ha-šāmayim wə-ʾet ha-ʾāreṣ, wə-yāʿas ʾafēlāh wə-ʾōr…

The Arabic from Qur’an, 6:1 is :

Al-ḥamdu li-llāhi allaḏī khalaqa al-samāwāti wa-l-ʾarḍa wa-jaʿala al-ẓulumāti wa-l-nūr.…

The English translation is : “Praise be to God, Who created the heavens and the earth and made the darkness and the light.…”

Conclusions

The usage of the word ʾĔlōhīm in the Hebrew Quran serves as a powerful linguistic and theological bridge that directly challenges the oft-repeated claim that Islam presents a fundamentally different conception of God. The evidence drawn from Hebrew translations — especially those produced by Jewish scholars such as Yosef Yoʾel Rivlīn — clearly demonstrates that the Arabic Allāh is regularly rendered as ʾĔlōhīm, the very term used throughout the Hebrew Bible to refer to the God of Israel. This correspondence is not incidental ; it is rooted in the shared Semitic etymology of both terms, with ʾĔlōhīm and Allāh stemming from a common proto-Semitic root for divinity.

The similarities are so linguistically and contextually obvious that it can no longer be denied — in the face of this textual evidence — that the two terms are related in both origin and meaning. Just as the Arabic Bible contains the word Allāh to denote the God of the Christians, the Hebrew Qur’an uses ʾĔlōhīm to represent the God of the Muslims. In both cases, we are not dealing with different deities but rather with different expressions of the same eternal monotheism articulated through sister languages.

Inshāʾ Allāh, this comparative evidence will serve to counter and disarm the falsehoods propagated by Christian missionary polemicists who claim, without basis, that Muslims worship a “different god” or that Allāh refers to a so-called moon god. These claims not only lack linguistic and historical credibility, but they also ignore the deep and ancient interconnectedness of the Abrahamic traditions. The usage of ʾĔlōhīm in the Hebrew Quran offers a clear rebuttal to these distortions and serves as a textual testimony to the unity of God across Semitic faiths.

And only God knows best.

- W.E. Vine, Merrill F. Unger, William White Jr., Vine’s Complete Exposition Dictionary, Thomas Nelson Publishers, Nashville, TN, 1996.[⤶]

- Reckendorf, Hermann. Der Koran ins Hebräische Übertragen. Leipzig : 1857.[⤶]

- See Yosef Yo’el Rivlin, Alkur’an /tirgem me-‘Arvit, Devir, Tel Aviv (1936−1945). More information is available here.[⤶]

- We have referred to A. Yusuf Ali, The Holy Qur’an : Text, Translation, and Commentary for the English translation of the Basmalah and the later translations of the Quranic verses involved.[⤶]