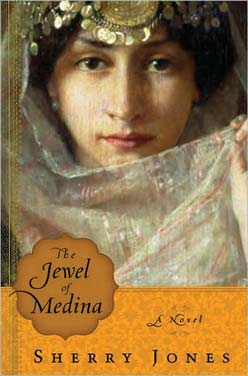

Journalist Sherry Jones, the Montana and Idaho correspondent for the international news agency the Bureau of National Affairs, maintains that she envisioned The Jewel of Medina, her fictionalized account of A’isha Abi Bakr, the child bride of Muhammad, as a “bridge builder.” But even before it was published, the novel became a casualty of the clash of civilizations.

After Denise Spellberg, associate professor of history and Middle Eastern studies at the University of Texas, assessed the manuscript as “a very ugly, stupid, piece of work” which turned sacred history into soft-core pornography and warned that publication could provoke violence, Ballantine Books, a division of Random House, consulted with security experts and then negotiated an agreement with Jones to terminate their $100,000 two-book contract.

Amid allegations of self-censorship and the suppression of free speech, two publishing houses — Beaufort Books in the US (whose list includes O.J. Simpson’s If I Did It) and Gibson Square in Great Britain — announced they would rush the novel into print. On September 27, the home of Martin Rynja, publisher of Gibson Square, was fire-bombed. Nonetheless, The Jewel of Medina has been — or will be — published in at least 15 countries.

The novel isn’t worth the attention it’s getting. As reliable, historically, as Disney’s Aladdin and the King of Thieves, The Jewel of Medina is a “chick lit” feminist tract, painted in purple prose. Then — and now — Jones’s A’isha claims, centuries after her death, “girls turn away because they don’t know the truth… That none of us is ever alive until we can shape our destinies. Until we can choose.”

Not your typical seventh-century Muslim maiden, A’isha begins her crusade against marital rape before she’s 10. She vows never to be “the poor girl underneath,” enduring “a woman’s life” with “downcast eyes and nary a whimper of complaint.” She’ll fight back — and if her husband doesn’t like it, “he could divorce me and I wouldn’t care. I’d rather be a lone lioness, roaring and free, than a caged bird without even a name to call my own.”

Then Jones goes phallic. Summoned to meet the prophet, A’isha hesitates, closing her eyes and taking a deep breath : “My future awaited on the other side — a fate chosen by others, as though I were a sheep or a goat fatted for this day.” Her mother pulls the curtain away : “What are you waiting for ? Ramadan?”

“No more fighting with sticks,” Muhammad tells her, in a bedroom filled with wooden soldiers, dolls, a jump rope and a sword. “I will teach you how to use the real thing.” As the prophet’s eyes changed, “as if catching flame,” the little girl waited for “the scuttling hands, the stinging tail… Soon I would be lying on my bed beneath, squashed like the scarab beetle, flailing and sobbing while he slammed himself against me. He would not want to hurt me, but how could he help it?”

Jones believes that The Jewel of Medina portrays Islam as, at bottom, an “egalitarian religion” and Muhammad as a “gentle, wise and compassionate” leader, who respected women, especially his wives. Thanks to the prophet, A’isha suggests, women could “inherit property, testify in hearings and write provisions for divorce into their wedding contracts.”

But the gender politics of the novel is, at best, confused. And Jones’s Muhammad has feet of clay. A man of physical passion, he is seduced by power, making strategic alliances through marriage. Muhammad changes Allah’s law at will and whim. Intent on marrying the wife of his adopted son, he declares that “we have been in error all these years.” Since Zayd does not carry his blood in his veins, “why should I hesitate?” In another self-indulgent about-face, he annuls the edict limiting a harem to four wives. And by ordering females to cover their faces, A’isha concludes, the prophet transforms himself “from a liberator of women into an oppressor of them.”

The Jewel of Medina is a platform for the propositions of the politically correct, circa 2008. An unmarried woman in Medina in 625 “with no family to support her and no skills,” A’isha claims, had only two prospects : begging and prostitution. As she walks through a tent city with the mother of the poor, the child-bride chides herself for moping while people struggled to survive. She drapes her wrapper around the shoulders and head of a child in tattered clothing to protect her “tender face” from the sun. “From now on,” A’isha concludes, “when I heard others denigrate the tent people as I’d once done, I’d make sure to tell them of their pride and dignity.”

You don’t know whether to laugh or cry. As she confesses in the “afterword” — and demonstrates in the novel with asides about gowns that “plunge down to the navel” and off-shoulder garments “that burst open like springtime” when the wearer dismounts a camel — Sherry Jones doesn’t know what it was like to be alive and a woman in seventh-century Arabia. She may have “huge respect and regard for the Muslim faith,” but she doesn’t display much knowledge about Islam, either. It’s an outrage that publication of this book — or any book — was held hostage to threats of violence. But as a work of historical fiction The Jewel of Medina is a non-precious stone that ought to be allowed to sink without a trace.