Introduction

In a study of logic, there is something which we call “undecidable propositions” or “meaningless sentences”, which are statements that cannot be determined because there is no contextual false. One of the classic examples cited is the Epiminedes’ paradox. Saul Kripke says :

Ever since Pilate asked, “What is truth?” (John XVIII, 38), the subsequent search for a correct answer has been inhibited by another problem, which, as is well known, also arises in a New Testament context. If, as the author of the Epistle to Titus supposes (Titus I, 12), a Cretan prophet, “even a prophet of their own,” asserted that “the Cretans are always liars,” and if “this testimony is true” of all other Cretan utterances, then it seems that the Cretan prophet’s words are true if and only if they are false. And any treatment of the concept of truth must somehow circumvent this paradox.

Saul Kripke, “Outline of a Theory of Truth”, Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 72, 1975, p. 690

Epimenides was Cretan and he said that “Cretans always lie”. Now, was that statement true or false ? If he was a Cretan and he says that they always lie, is he then lying ? If he is not lying then he is telling the truth and therefore Cretans do not always lie. We can see that since the assertion cannot be true and it cannot be false, the statement turns back on itself. It is like stating “What I am telling you right now is a lie”, would you believe that or otherwise ? This statement thus has no true content. It cannot be true at the same time it is false. If it is true then it is always false. If it is false, it is also true.

Paul Creates The Paradox

Well, in the New Testament, the writer is Paul and he is talking about the Cretans in 1 Titus, as follows :

A prophet from their own people said of them “Cretens are always liars, wicked brutes, lazy gluttons.” This testimony is true. For this reason correct them sternly, that they may be sound in faith instead of paying attention to Jewish fables and to commandments of people who turn their backs on the truth. (Titus 1:12 – 14)

Notice that Paul says that one of their own men — a prophet — said that “Cretans are always liars” and he says that what this man say is true. It is a small mistake, but the point is that it is a human mistake. It cannot be a true statement at the same time that it is a false statement. Thus, how can Christians claim that the writers of the New Testament — in this case, Paul — had “inspiration” from God ?

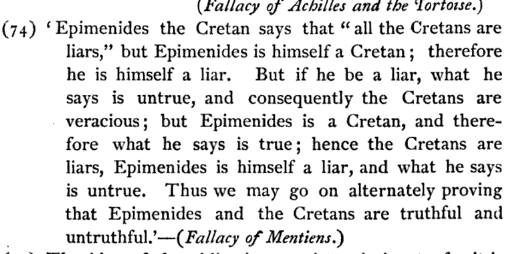

Noted British logician Professor Thomas Fowler, who was in the 1800s, the Professor of Logic in Oxford and Fellow of Lincoln College, to sum up the problem created in Titus 1:12 that must necessarily falsify the inerrantist and the fundamentalist.

“Epimenides the Cretan says, ‘that all the Cretans are liars,’ but Epimenides is himself a Cretan ; therefore he is himself a liar. But if he be a liar, what he says is untrue, and consequently the Cretans are veracious ; but Epimenides is a Cretan, and therefore what he says is true ; saying the Cretans are liars, Epimenides is himself a liar, and what he says is untrue. Thus we may go on alternately proving that Epimenides and the Cretans are truthful and untruthful.“

Fowler, T., The Elements of Deductive Logic : Designed Mainly for the Use of Junior Students in the Universities (Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1875), p. 171

Some Christians have taken the position that a strictly logical approach to Epimenides’ statement can result in it not being a paradox after all. If it is not a paradox, one may argue that Paul’s calling it “true” was a subtle bit of mockery with tremendous foresight regarding later developments in logic. If that is the case, then maybe Paul’s statement actually was inspired. For example, while discussing Paul’s comments in the epistle to Titus, one Christian theological periodical concedes that “one of the very greatest of Christian thinkers enters the logic books wearing a dunce’s cap“

There is the ancient paradox of Epimenides the Cretan, who said that all Cretans were liars. If he spoke the truth, he was a liar. It seems that this paradox may have reached the ears of St. Paul and that he missed the point of it. He warned, in his epistle to Titus : “One of themselves, even a prophet of their own, said The Cretans are always liars.” Actually the paradox of Epimenides is untidy ; there are loopholes. Perhaps some Cretans were liars, notably Epimenides, and others were not ; perhaps Epimenides was a liar who occasionally told the truth ; either way it turns out that the contradiction vanishes.

Wilard Van Orman Quine, The Ways of Paradox and Other Essays (Harvard University Press, 1997), p. 6

The question that arises now is how Quine was able to figure out that maybe other Cretans were liars or maybe Epimenides sometimes told the truth. Epimenides is clearly saying that Cretans are always liars. Every time a Cretan speaks, he is lying, so how could the statement ever allow for a Cretan (be it Epimenides or some other Cretan) to speak the truth ? The reasoning is genius, and goes as follows : the obvious assumption behind the belief that the statement is paradoxical is that if all Cretans lie, then Epimenides is lying, so if his statement is true, it is false. In that sense it seems like any other pseudomenon. From here, if we consider the statement false, we are no longer forced into the kind of paradoxical vicious circle that a true pseudomenon (like “this sentence is false”) pushes us into. Commenting on a similar line of argumentation, Schoenberg writes the following :

We may feel intuitively that the argument is paradoxical ; yet, from a formal logic point of view, it does not really have the look of a paradox. It looks simply like reductio ad absurdum proof of the falsity of ‘All Cretans are liars.‘

Judith Schoenberg, Belief and Intention in the Epimenides, Philososphy and Phenomenological Research, Vol. 30, 1968, p. 270

Thus, as Quine noted, it is not inconsistent to assume that some other Cretan does not always lie, or that some other statement by Epimenides was true. Prior explains this quite well :

If we treat the Cretan’s assertion as true, and so assume that nothing true is ever asserted by a Cretan, it follows immediately that the Cretan’s assertion is false. If, however, we treat it as false, there is no way of deducing from this assumption that it is true. We can, therefore, consistently suppose it to be false, and this is all we can consistently suppose. But to suppose it false (considering what the assertion actually is) is to suppose that something asserted by a Cretan is true ; and this of course can only be some other assertion than the one mentioned.

A. N. Prior, “Epimenides the Cretan”, Journal of Symbolic Logic, Vol. 23, 1958, p. 261

A paradoxical statement has no discernable truth value, but the statement by Epimenides can be seen as having a truth value (i.e. it is false), and if that is the case we can reinterpret the statement as not being paradoxical. However, establishing a truth value for the statement does not escape the problem with Paul’s claim since the saying of Epimenides is false. As Prior noted above, we cannot consider the statement true (as Paul did). If sophisticated analysis determines after all that this statement by Epimenides is not paradoxical, and thus has a truth value, the only consistent supposition we can make is that it is false.

Conclusion

In the end, the following seven-point syllogism completes our argument :

- Paul claims a Cretan uttered a certain proposition.

- The proposition is not true.

- Paul claims the proposition is true.

- Paul’s claim is an error.

- Paul’s writings are errant rather than inerrant.

- Errant scripture is not inspired scripture, as held on by Muslims.

- Therefore, Paul was not inspired.

Hence, whether the statement is meaningless or false, the basic argument which we have raised still stands. The conclusion of the seven point syllogism given above still rings true : Paul was not inspired.

And only God knows best !

A further discussion of the syllogism made here was elaborated in Epimenides Paradox Revisited.