Philosophical theism, in contemporary times, has been dominated by philosophers who are Christians. These theistic philosophers have published a great amount of literature defending the rationality of belief in God, and any participant in the great debate will surely be familiar with the names of intellectual giants like Alvin Plantinga, Richard Swinburne, William Lane Craig, among many others.

Swinburne, for example, gives theistic belief, and in particular Christian belief, philosophical treatment in toto. I have noticed the following progression in his case for Christianity. First, he argues that the notion of ‘God-talk’ is perfectly coherent, and there are no a priori reasons to reject theistic belief.

Of course, not all Christian philosophers have the evidentialist enthusiasm of Swinburne. The reformed epistemologists, spearheaded by Alvin Plantinga and Nicholas Wolterstorff, approach theistic belief analytically, but not on evidentialist grounds.

These prefatory remarks are important to bear in mind, since I now wish to look at the philosophical tenability of the (orthodox) Christian depiction of God, which I feel has been largely ignored by contemporary Christian philosophers. My analysis will only be confined to divine ontology, and the contention I will be arguing for is that ‘Christian monotheism’ is ontologically incoherent. This has further implications for Christian particularism (in so far as it is understood by Pauline ontology), for if, on a priori grounds, the Christian depiction of God is impossible, then it follows a fortiori, that the doctrinal particulars which are contingent on this erroneous ontology cannot be true.

I am writing this piece with the intention of hearing from Christian philosophers who adhere to the Pauline ontology of God, believe in its coherence, and are willing to discuss the matter on rational grounds.

[toc]

Locating Our Topic

Naturally, no insight is free from presuppositions, and so I will need to state the position from which my analysis is going to depart. The terminus of natural theology is usually a metaphysical postulation, some ‘first cause’, ‘intelligent designer’, ‘law giver’, or the like. The theist, of course, argues that this being is God. According to Swinburne, to state that God exists is to state that there is :

“A person without a body (i.e. a spirit), present everywhere, the creator and sustainer of the universe, a free agent, able to do everything (i.e. omnipotent), knowing all things, perfectly good, a source of moral obligation, immutable, eternal, a necessary being, holy, and worthy of worship.“

Swinburne, The Coherence of Theism, p. 1

This is a definition of God that Jewish-Islamic theism can easily accept without any major difficulties, for this is the common understanding of God in Western theism. As far as divine ontology goes, it is a monotheistic definition : there is only one God, the Creator and Sustainer of the universe who exists. Understood thus, there is nothing obviously incoherent about postulating such a being. I will further assume that there are no a priori reasons for considering the existence of such a being (taking Swinburne’s definition) as impossible, due to some logical contradiction or the like (a defence of such a contention will be the task for another day).

Now the questions I wish to explore are these : When Swinburne’s definition of God is unpacked, and further explicated within orthodox Christian theism, is it still coherent ? Are there any a priori reasons for considering it to be incoherent, and thus impossible ? If so, what implications are there for orthodox Christian particulars ?

Stating Trinitarian Ontology

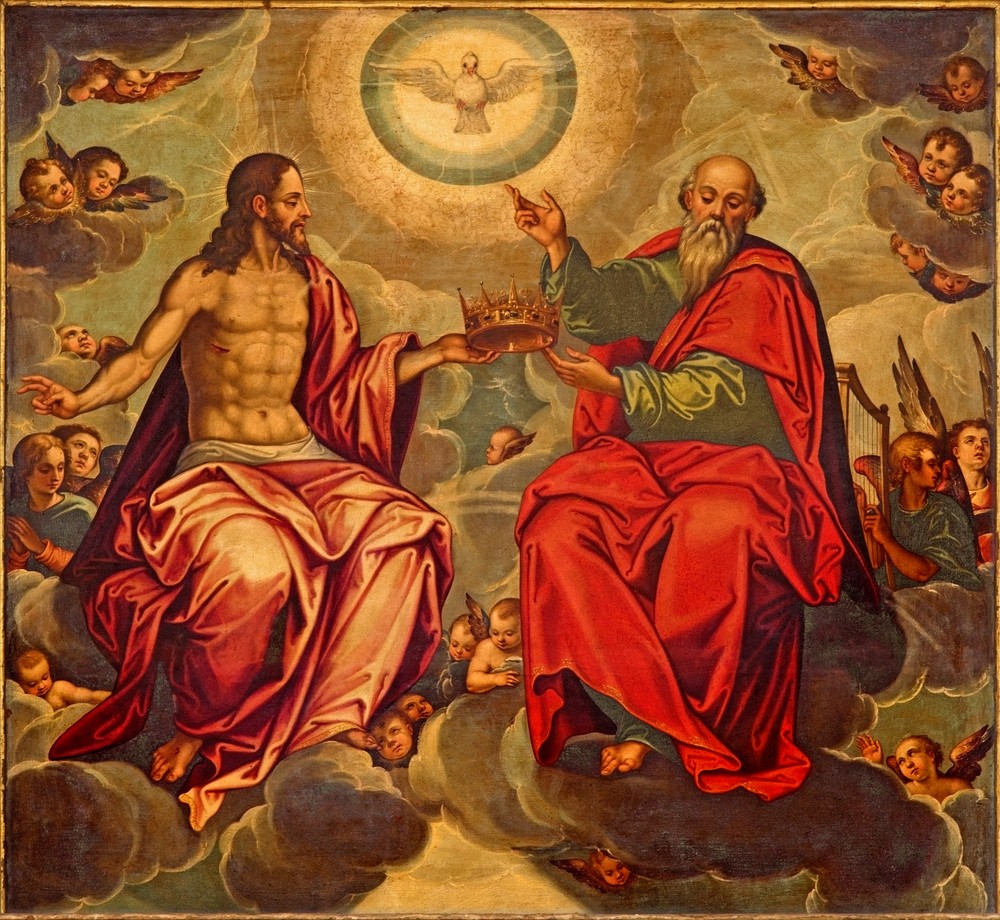

According to orthodox Christianity, although there exists a God as understood by Swinburne, He is tri-personal. In other words, God is three distinct persons (The Father, Son and Holy Spirit) in one substance, and yet He is still one being. To understand this, we can do no better than turn to the Athanasian Creed, where we find the following existential statements :

“[T]he Catholic Faith is this, that we worship one God in Trinity and Trinity in Unity. Neither confounding the Persons, nor dividing the Substance. For there is one Person of the Father, another of the Son, and another of the Holy Ghost. But the Godhead of the Father, of the Son and of the Holy Ghost is all One, the Glory Equal, the Majesty Co-Eternal. Such as the Father is, such is the Son, and such is the Holy Ghost … So the Father is God, the Son is God, and the Holy Ghost is God. And yet they are not Three Gods, but One God … there is One Father, not Three Fathers ; one Son, not Three Sons ; One Holy Ghost, not Three Holy Ghosts … He therefore that will be saved, must thus think of the Trinity.“

The Athanasian Creed, available online. I have summarized the idea behind the doctrine of the Trinity, although it is suggested the reader scrutinize the entire text.

Trying to make sense of the creed can be difficult, and therefore we can follow philosopher Richard Cartwright

- 1. The Father is God.

2. The Son is God.

3. The Holy Spirit is God.

4. The Father is not the Son.

5. The Father is not the Holy Spirit.

6. The Son is not the Holy Spirit.

7. There is exactly one God.

From this point onwards, when I refer to the Christian understanding of God, it is in reference to the Athanasian Creed that my arguments are to be understood.

Can A Tri-Personal Deity Exist ?

Answering this question is very much an ontological exploration. We need to distinguish between a priori and a posteriori answers to the question of existence. By a priori answers, I am referring to answers which speak of conceptual possibilities or impossibilities. For example, there is a conceptual possibility that there exists in the world a unicorn. There is nothing in the definition of a unicorn which would immediately render its existence impossible. On the other hand, it is conceptually impossible that there exists in the world a married bachelor, since the notion of a married bachelor is incoherent. We know immediately a priori that such a being could not exist, ever.

By a posteriori answers, I am referring to propositions which we know the truth or falsity of through experience. Thus, although the existence of a unicorn is conceptually possible, most people do not believe that unicorns exist because of the lack of experience they have had, or lack of evidence. However, one would always be open to the evidence, since unicorns could exist. But it would be absurd to seek evidence for the existence of married bachelors, since it is conceptually impossible for such beings to exist.

Here, I am concerned with the definition of the Trinity, propositions (1)-(7) stated above. If any two of these propositions are contradictory, then it would be conceptually impossible for God, in so far as He is understood in orthodox Christian theism, to exist. And therefore, assessing the a posteriori evidence for or against the doctrine of the Trinity (as is often the case with the Biblical data) would be as meaningless as entertaining a married bachelor’s request for divorce.

Let the Father be designated by x, the Son by y, and the Holy Spirit by z. God, as defined by Swinburne, can be designated by G. As Cartwright notes, one way to interpret the creed is to take the verb ‘is’ and understand it to mean ‘is identical with’

Another possibility is to construe G as a general term

It seems we have a dilemma : if x, y and z are identical with G, then we simply have one person, or three names for one person. The heretical position of modalism comes to mind, where the eternal coexistence of the Father, Son, and the Holy Spirit is denied. But if x, y and z are a G (i.e. belong to a genera), then one has three divine persons, which of course is another heretical position : tri-theism. In the first instance, the contradiction can be removed by altering propositions (4)-(6). In the second, by altering (7). But taken altogether, (1)-(7) portray an inconsistent set. It follows ipso facto that the Christian God, as He is depicted in the Creed, cannot possibly exist.

Implications For Christian Particularism

Orthodox Christian ontology, as depicted in the Athanasian Creed, forms the basis for a number of Christian particulars. And these particulars are contingent upon the truth of the Christian ontology of God. The implications of ontological incoherence of the Trinity are that certain doctrinal particulars simply cannot be true. For example, the divinity of Jesus (the second person of the Trinity took on human form), the incarnation (which involves the second person in the Trinity being completely God and man simultaneously), etc. There seems to be an a priori blockade that prevents these doctrinal particulars from even getting off the ground.

Conclusions

To conclude, the doctrine of the Trinity as presented in the Athanasian Creed depicts an ontologically incoherent model of God. To dissolve the contradictions which arise from analyzing the Creed, one can either reject the plurality of persons and hold that there exists a single person with different names or modes.

Alternatively, one can embrace tri-theism. As long as one is committed to neither confounding the persons, nor dividing the substance, as the Creed would have us do, one is holding beliefs about God which are logically inconsistent. And if one is to remain consistent with the philosophical treatment of theism in contemporary philosophy by the likes of Swinburne and Craig, it follows that the doctrine of the Trinity, and its relation to ‘Christian monotheism’ — being profoundly irrational — should be abandoned.