Preamble

-

We believe in…one Lord Jesus Christ, the only-begotten Son of God, begotten of the Father before all worlds, God of God, Light of Light, Very God of Very God, begotten, not made, being of one substance with the Father by whom all things were made ; who for us men, and for our salvation, came down from heaven, and was incarnate by the Holy Spirit of the Virgin Mary, and was made man…

These extraordinary words express the faith of the Christian church since it formulated them in a creed in 325AD at the Council of Nicea. Jesus is identified unequivocally as “very God” of “very God”, of the same substance as the Father. In a word, Jesus is God.

However, unknown to the vast majority of Christians who faithfully fill the pews each week, since the nineteen century historians of the Bible have attempted to look afresh at the person of Jesus of Nazareth to see what his life signified to those first century writers who wrote the canonical gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John.

For the purposes of this study I want to focus on one aspect of this ongoing enquiry into Christian origins : the earliest recoverable christology. By which I mean the study of those beliefs held (as far as we can now determine) about Jesus of Nazareth by his immediate followers ; those whose lives chronologically overlapped that of Jesus but who never met him (e.g. the apostle Paul); and the beliefs of the evangelists who composed our four gospels.

It is clear that there has been a development in the way Jesus is presented in the pages of the New Testament. Even a cursory reading of the earliest gospel to be written, that of Mark, shows us a very human figure, a man who prays to God (1:35); is unable to work miracles in his own town (6:5); confesses ignorance about the date of the End of the world (13:32); and who apparently despairs of God’s help at the crucifixion (15:34).

If we then read the chronologically last of the four gospels, that of John, we move into a different world. Here Jesus seems to move effortlessly through his ministry, who is clearly portrayed as a divine figure, indeed as “God” himself. The creed quoted above finds a familiar echo in the prologue to John’s gospel. Chapter one, verse 14 ranks as a classic formulation of the Christian belief in Jesus as God incarnate : ‘The Word became flesh and dwelt among us’. So even this brief survey has shown the enormous development which occurred in less than two generations after Jesus was taken up to God.

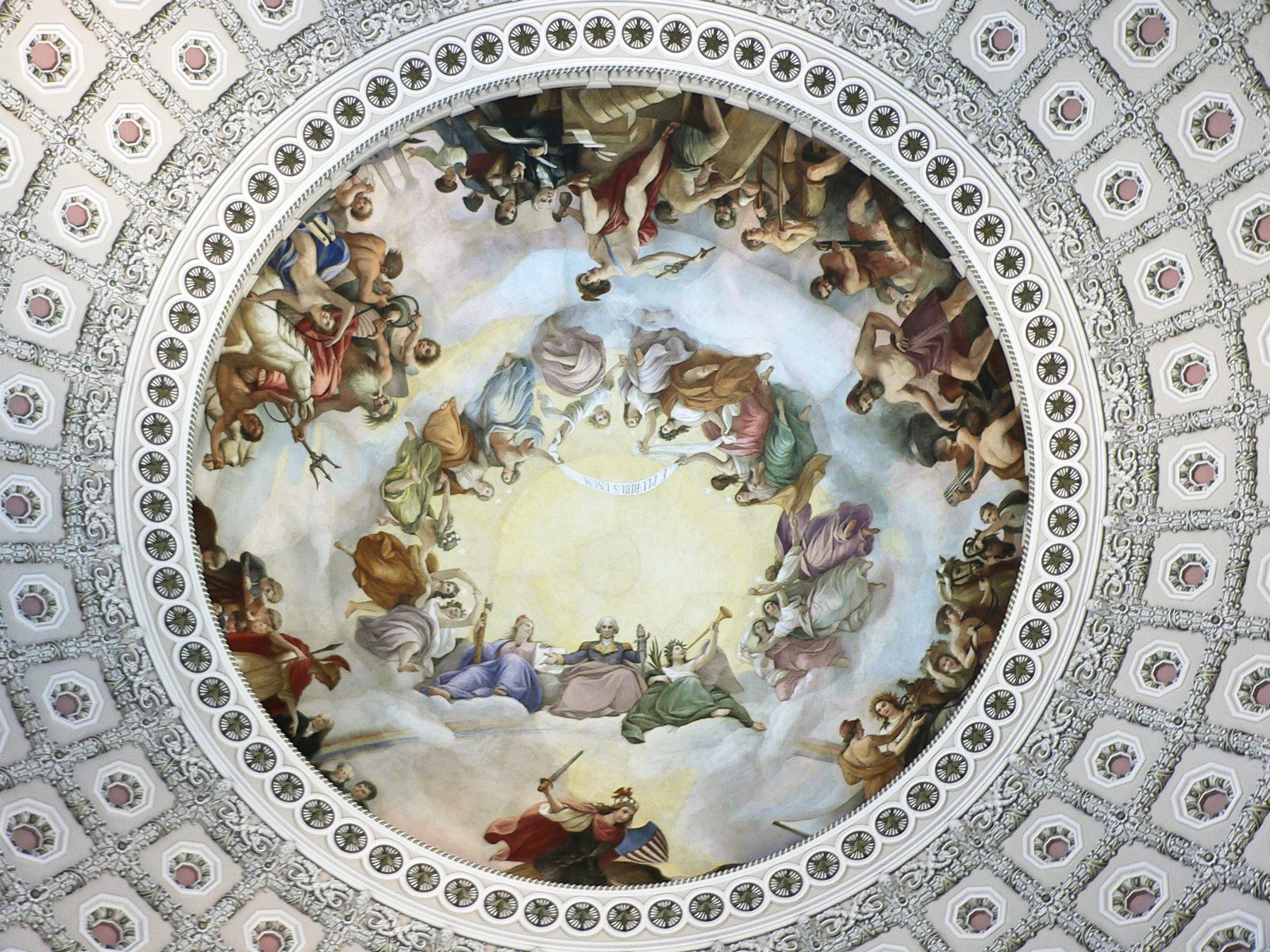

I believe it is now possible to pinpoint one instance in the synoptic gospels where we can actually witness the writer’s intentional elevation of Jesus from a man into a divine being. We can observe in one small but significant instance the remarkable apotheosis of Jesus.

I do not claim that this example explains but a small fraction of the theological movement that lead ultimately to the Nicaean creed. In fact a large part of the Trinitarian doctrine was initiated in embryonic form by the apostle Paul in the 40s and 50s of the first century.

James D.G. Dunn perhaps more than any other scholar made truly significant contributions to Jesus research. His book Christology in the Making, a New Testament Inquiry into the Origins the Doctrine of the Incarnation is vital reading for the student of Christology.

In his Forward to the Second Edition of the book (p xii) he asks whether the Christological development to be found in the NT is either an organic development (tree from seed) or an evolutionary development (mutation of species)?

It will be clear to the reader that I believe it is the latter. I will consider this in more detail in my conclusion at the end.

Let us now survey the evidence.

1. Introduction

Edward Schweizer in an article published in 1959 stated : “The idea of the pre-existence of Jesus came to Paul through Wisdom speculation.“

Turning to the Synoptic gospels we find that “Jesus appears as bearer or speaker of Wisdom, but much more than that as Wisdom itself. As pre-existent Wisdom Jesus Sophia…“

In this article I intend to focus exclusively on the synoptic gospels and their formulation and development of Wisdom christology. To my knowledge the most thorough study to date on this subject is to found in the work of Dunn in Christology in the Making, A New Testament Inquiry into the Origins of the Doctrine of the Incarnation

2. Wisdom in Pre-Christian Judaism

To get our inquiry going we must ask who or what was this Wisdom whose functions and descriptions are attributed to Christ in the New Testament ? To get an answer we need to inquire into the meaning of this concept in those Second Temple Jewish texts before the rise of Christianity. This will provide us with a historical “context of meaning” with which to evaluate NT texts. The central passages can be found in Job 28, Proverbs 8 22 – 31, Ecclesiasticus 24, Baruch 3.9−4.4, Wisdom of Solomon 6.12−11.1, 1 Enoch 42 and various references to Wisdom in Philo.

So who or what is Wisdom in this literature ? Dunn lists a summary of the current options in what he calls “a still unresolved debate”.

The main options are as follows :

a) Wisdom is a divine being, as parallels in Egyptian and Mesopotamian texts

b) Wisdom is a hypostasis – i.e. a “quasi-personification of certain attributes proper to God, occupying an intermediate position between personalities and abstract beings“

c) Wisdom is simply a personification of a divine attribute

d) Wisdom is the personification of cosmic order (for example the Stoic language of Wisdom of Solomon)

So, if we are to answer with any historical precision the question ‘What did it mean that the first Christians identified Christ as Wisdom?’ we must come to a decision from the list of options as to which is the best interpretation of these Old Testament and inter-testamental passages.

When these passages are considered in chronological order we see a development in the concept of Wisdom. Dunn sees this as ‘due in large part to the influence (positive and negative) of religious cults and philosophies prevalent in the ancient near east at that time.’

“Job 28 : Surely there is a mine for silver, and a place for gold which they refine…But where shall wisdom be found?”

Clearly there is no personification here or wisdom as a divine attribute. Von Rad describes it as “the order given to the world by God”.

In Proverbs 8 Wisdom is robustly personified as a woman : ‘Does not wisdom call out ? On the heights along the way, where the paths meet, she takes her stand…she cries out aloud’. Dunn sees talk of Wisdom as a woman as an attempt to counteract the pernicious influences of the Astarte cult by portraying Wisdom as much more attractive than the ‘strange woman’ he warns against in Proverbs 2, 5, 6, and 7.

Wisdom in the Wisdom of Solomon is the personification of cosmic order

She reaches mightily from one end of the earth to the other,

and she orders all things well (8.1);[Wisdom, who] sits besides God’s throne (9.4).

Stoic thought about cosmic reason is particularly evident in 7.22ff.:

intelligent, holy, unique, manifold, subtle, mobile,…

For wisdom is more mobile than any motion ;

because of her pureness she pervades and penetrates all things.

For she is a breath of the power of God,

and a pure emanation of the glory of the Almighty.

Dunn concludes his in-depth survey of the Jewish literature with the view that no worship is ever offered to Wisdom ; Wisdom has no priestly cast in Israel. “When set within the context of faith in Yahweh there is no clear indication that the Wisdom language of these writings has gone beyond vivid personification.“

Second Temple Judaism therefore, as far as the textual evidence goes, suggests that there was no thought of Wisdom as a “hypostasis”

3. Q and the Contrasting Redactions of Matthew and Luke

What is Q ?

The Q document (or just “Q” from the German Quelle, “source”) is a postulated but now lost textual source for the gospels of Matthew and Luke.

The recognition of 19th century NT scholars that Matthew and Luke share much material not found in their generally recognised common source, the gospel of Mark, has suggested a second common source, called Q. It seems most likely to have comprised a collection of Jesus sayings.

The contrasting redactions of Matthew and Luke

Having briefly discussed the nature of Jewish Wisdom language I now want to analyse how the synoptic gospels utilise such language in their redaction of the Q logia, and why this is so significant for our understanding of the historical Jesus and how later generations came to portray him.

I want to focus on Matthew chapter 23 and the parallel passages in Luke. In this chapter Mathew seems to identify Jesus as Wisdom. He does this by editing the Q material at his disposal. It is possible, by a comparison with Luke, to demonstrate how this was done. Dunn gives us several examples of this redaction but I want to focus on one, partly for simplicity’s sake but also because my example most clearly demonstrates this fact. (It might prove helpful for the reader to read these quotations in their larger gospel context).

Luke 11.49 : Therefore also the Wisdom of God said, ‘I will send them prophets and apostles, some of whom they will kill and persecute’…

Matt. 23.34 : (Jesus’ words) ‘Therefore I send you prophets and wise men and scribes, some of whom you will kill and crucify, and some you will scourge in your synagogues and persecute from town to town…’

Here we have a Q saying. I would argue that Luke’s version is nearer to the original Q form, because it is more probable that Luke’s Wisdom utterance : ‘I will send them…’ is more likely to be the original than that he deliberately altered a precious first person saying of Jesus : ‘I send you…’

So in Q we have Jesus quoting a saying of Wisdom where she promises to send emissaries to Israel, and Jesus is the spokesman of Wisdom. So much is clear.

When we turn to Matthew’s redaction of Q, he has turned the saying of Wisdom into a saying of Jesus himself. For Matthew, Jesus is Wisdom.

How are we to assess the significance of Matthew’s Wisdom christology ? The synoptic tradition allows us to see the changing thought of Christians in the first century. We are fortunate to be able to compare and contrast Matthew and Luke with their sources Mark and Q. With close and intelligent attention to the texts we can detect where Matthew and Luke have altered or expanded the traditions about Jesus.

Not all changes to Mark and Q are theologically significant. Sometimes the evangelists abbreviate a longer story in Mark, or retell a story about Jesus to bring out a particular dramatic point.

Here however I want to argue that the evangelist in his redaction of Q (here and else where, see 11.25−30 ; 23−37−9) has made a move of incalculable theological significance the gravity of which is not sufficiently recognised by Dunn in his otherwise perceptive discussion of the issue.

I refer of course to the apotheosis of Jesus implicit in Matthew’s narrative. I want to provide a snapshot of this metamorphosis. Dunn’s characterisation of this transformation as a “transition” is too weak ; we are dealing with something of profound ontological significance.

4. Christ as Wisdom in Matthew’s Gospel and the Apotheosis of Jesus of Nazareth

Mathew, without any apparent fanfare has made a change in Jesus’ ontological status from Jesus as a messenger of Wisdom to Jesus as Wisdom. Historically one may postulate that this opened up the possibilities for a subtle deification of Jesus, which becomes explicit in the chronologically later parts of the NT (Prologue to John’s gospel comes to mind). This means that we have a fundamental shift away from the historical Jesus of Nazareth towards the Trinitarian speculations of the patristic era.

As Dunn concludes, “when we press back behind Q, insofar as we reach back to the actual words of Jesus himself, the probability is that Jesus’ own understanding of his relation to Wisdom is represented by Q rather than by Matthew.“

If the gospel was written after 70 CE (the consensus of scholars), the outbreak of hostility between rabbinic Judaism and Jewish Christianity which occurred after the fall of Jerusalem in AD70 (which is implied by Matthew 23) may have been provoked by what to Jewish monotheistic ears trained to value the unity of the Godhead, must have sounded like the rankest blasphemy in attributing deity to a creature.

5. Conclusion

It will be apparent from this analysis that at least one writer known to us many years after Jesus’ ascension, by his deliberate editing of the gospel sayings of Jesus, took a completely new step : he applied Wisdom categories that had previously dramatised Gods saving actions in the world to a man who lived only decades earlier.

The most sophisticated attempt known to me to save orthodox Christian teaching in the face of early Christianity’s changing doctrines about Jesus is to be found in the celebrated Victorian churchman John Henry Newman. He was concerned to defend the truth of Catholic teaching about Jesus against historical evidence suggesting that the dogma of the deity of Christ was not church teaching till centuries after Jesus’ time. He wrote a highly influential work An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine.

It was composed in 1845, when Newman was halting midway between two forms of Christianity. Its aim was to explain and justify what Protestants regarded as corruptions and additions to the primitive Christian creed, and to show these to be legitimate developments. In a series of eloquent and erudite analogies, he seeks to show that the present highly complex doctrines of the Church lay in germ in the original depositum of faith, which has evolved or developed through progressive unfolding and explication.

Newman was writing at a time when Victorian England was coming to terms with the notion of development in history and science. The idea of evolutionary change was part of the zeitgeist, and soon Darwin would publish his monumental Origin of Species.

But was Newman right ? Did the church’s developing doctrines about Jesus simply make explicit what had been implicit in the truth about Jesus ? Could one still credibly believe that Jesus believed himself to be Almighty God as the Nicaean Creed suggests ? Would Jesus himself be content with what the church has done with his memory and teaching ?

In answer to these questions I would like to leave the last word to the Jewish scholar Geza Vermes, who has spent over 50 years of scholarly activity studying Judaism, the Dead Sea Scrolls, the New Testament and Jesus.

By the end of the first century Christianity had lost sight of the real Jesus and of the original meaning of his message. Paul, John and their churches replaced him by the otherworldly Christ of faith, and his insistence on personal effort, concentration and trust in God by a reliance on the saving merits of an eternal, divine Redeemer. The swiftness of the obliteration was due to a premature change in cultural perspective. Within decades of his death, the message of the real Jesus was transferred from its Semitic (Aramaic/Hebrew) linguistic context, its Galilean/Palestinian geographical setting, and its Jewish religious framework, to alien surroundings…Jesus, the religious man with an irresistible charismatic charm, was metamorphosed into Jesus the Christ, the transcendent object of the Christian religion.

The distant fiery prophet from Nazareth proclaiming the nearness of the kingdom of God did not mean much to the average new recruit from Alexandria, Antioch, Ephesus, Corinth or Rome. Their gaze was directed towards a universal saviour and even towards the eternal yet incarnate Word of God who was God.

Geza Vermes, The Changing Faces of Jesus, Penguin, 2000, p. 263

Further Thoughts

At the end of the day the considerations of this paper do not exist in a vacuum. If I am broadly on target in my analysis then this matters profoundly. In the arena of the world’s religions, claim and counter claim about religious truth calls each of us to respond thoughtfully and with courage.

If orthodox Christianity, the Christianity of the Trinitarian creeds, is now shown to be too radically discontinuous with the historical flesh and blood Jesus who walked the streets of Jerusalem 2000 years ago, then we are obliged to look elsewhere for unalloyed revelation.

Someone once asked the noted English Muslim writer Gai Eaton why there is no historical criticism of the Qur’an as there is of the Bible. He answered :

There is a misunderstanding : the Bible is made up of many different parts, compiled over many centuries and it is possible to cast doubt upon one part without impugning the rest ; whereas the Qur’an is a single revelation, received by just one man, either you accept it for what it claims to be, in which case you are a Muslim or you reject this claim, and so place yourself outside the fold of Islam.

Gai Eaton has written some of the most acclaimed books about Islam in the English language. Particularly recommended is Islam and the Destiny of Man. See reviews here.

Last Updated on August 6, 2017 by Bismika Allahuma Team