One of the big questions nobody has asked about Mel Gibson’s The Passion Of The Christ is this : If the crucifixion was a historic event and so central to the Christian Gospel, why is it that there is no evidence whatever of a man on a cross in Christian art and monuments for almost seven centuries ?

Not until 692 CE, in the reign of Emperor Justinian II, was it decreed that henceforth instead of a lamb (the zodiacal sign of Aries) fixed on the cross, the figure of Jesus be placed there instead. Another question : How is it that the earliest known figure of any man on a cross comes from about 300 BCE and that “person” is not Jesus but Orpheus, a mythical Greek sun-god ?

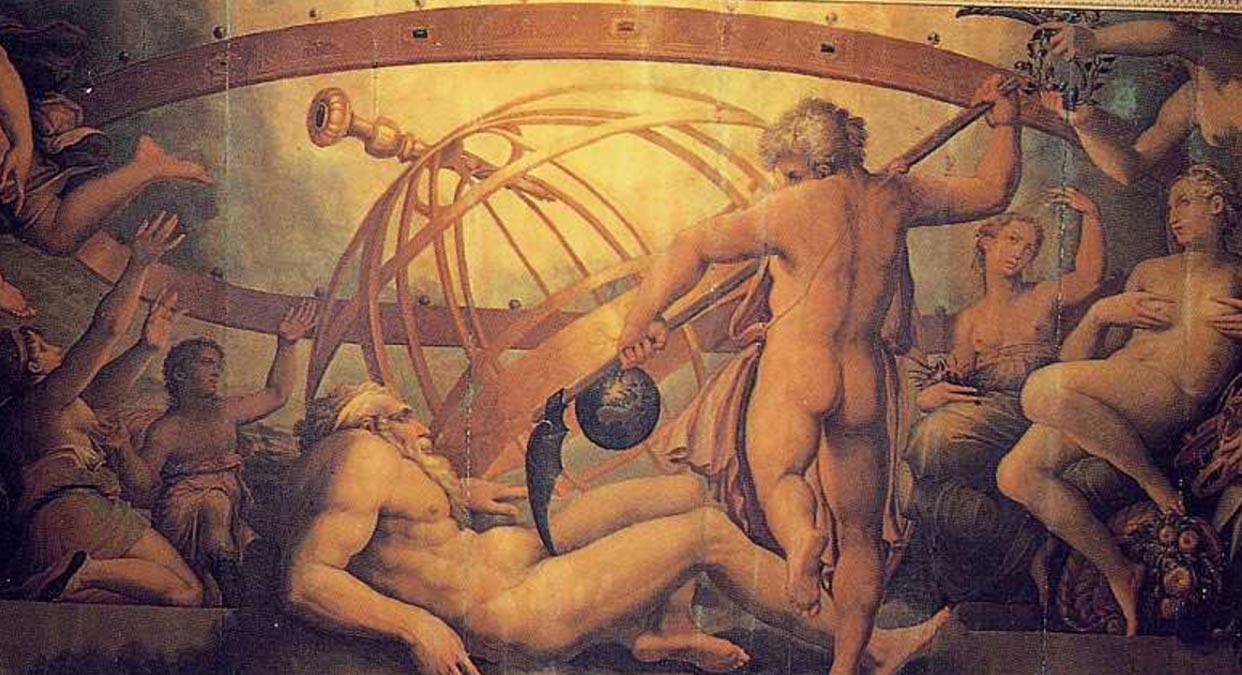

More significantly, why were there so many crucified or otherwise mutilated saviour-gods in antiquity ? One has only to think of the cutting to pieces of the later resurrected Osiris, or of Horus, or Dionysus, or Prometheus, or many more similarly tortured hero-divinities. Scholar Kersey Graves once wrote a book titled The World’s Sixteen Crucified Saviours : Christianity Before Christ. Seminary didn’t tell me that.

Surely the question must arise in minds that are accustomed to thinking and not just to accepting every story presented by state, religion, or the media at its surface value : Could there be some deeper meaning to this whole dying-rising god myth that pops up everywhere in the ancient world ? Was Mel Gibson’s greatest error not the ubiquitous and ever-so-carefully filmed gore in his two-hour sermon but the fact that he took absolutely literally something that can only be properly understood in the context of what crucifixion symbolism is all about ?

Make no mistake : The ancient sages who devised the great myths of Sumer, Chaldea, Egypt, and Greece had not the slightest interest in external history as we know it. Their major concern was the eternal truths of the human heart and the secrets of our inner, spiritual evolution.

Every god in every ancient religion had to suffer and die to depict two realities :

That each of us is a bearer of a fragment or spark of deity. God has become flesh in each of us. This is the God within or, in Christian terms, “the Christ in you.” It’s the inner meaning of the Christian doctrine of the Incarnation.

This was a costly sacrifice, a divine outpouring in love and pity for the animal-human that could only be expressed symbolically as a tearing into pieces of God’s very being. The ancients said : “The gods distribute divinity.” The giving out of pieces of bread at a Eucharist — an almost universal phenomenon globally in every early culture — is precisely about this sacrificial distribution of divine energies. The body of humanity and the “body” of God are re-membered or put back into one grand harmony in this symbolic act. The same is true of the shared cup of wine — a ritual partaking of the spiritual essence of God’s life.

However, in the 3rd century CE, the Church succumbed to the temptation to pander to the ignorance of the masses and so took the old esoteric doctrine, simplified it and turned it into literalized history. The truth about God coming in man — i.e., into every human — to raise us up, became a literal story about God coming as a man.

To make sure this story stuck, all pagan opposition was quelled with an unequaled fury. Mystery schools and philosophical academies were closed down, libraries of books were burned, and anathemas were hurled at all who dared to raise objections. Those who risked everything by pointing out that the Christians had taken over all the old Pagan myths, rites, and ceremonies but transformed them by literalizing everything were either banished or killed.

That so-called “pious frauds,” forgery and deceit of every kind were widely used in a cover-up is testified to by some of the early Christian apologists themselves. Even the major church historian, Eusebius — as shifty a writer as one could imagine, according to Edward Gibbon — gloated over the fact that he managed (in his account) to “make everything right” for the Church.

There is glorious good news at the heart of the Christian message but Gibson’s film with its ponderously literalist approach doesn’t even come close to it. It’s small wonder there is so much violence in the world if the God behind and through it all condones — no, demands — the literal kind of violence Gibson has proved himself so proficient at putting on the screen.

But, it’s not only the violence that is so off-putting. It’s the misunderstanding of what the New Testament drama is actually about. One can’t blame Gibson. The Church itself has to face the enormity of the harm its failure to understand its own message has brought to millions through the centuries.

[cite]

Last Updated on September 23, 2017 by Bismika Allahuma Team