There are three sources of documentation for the history of the New Testament text — first, the Greek manuscripts ; second, the versions and finally the patristic quotations.

The only item now left to examine are the New Testament versions or translations.

According to the polemicist and missionary, Jay Smith :

- We have today in our possession 5,300 known Greek manuscripts of the New Testament. [For any given book, there are between 100 and 1000 manuscripts], another 10,000 Latin Vulgates, and 9,300 other early versions (MSS), giving us more than 24,000 manuscript copies of portions of the New Testament in existence today ! (taken from McDowell’s Evidence That demands a Verdict, vol.1, 1972 pp. 40 – 48 ; and Time, January 23, 1995, p. 57).

Another Christian apologist writes :

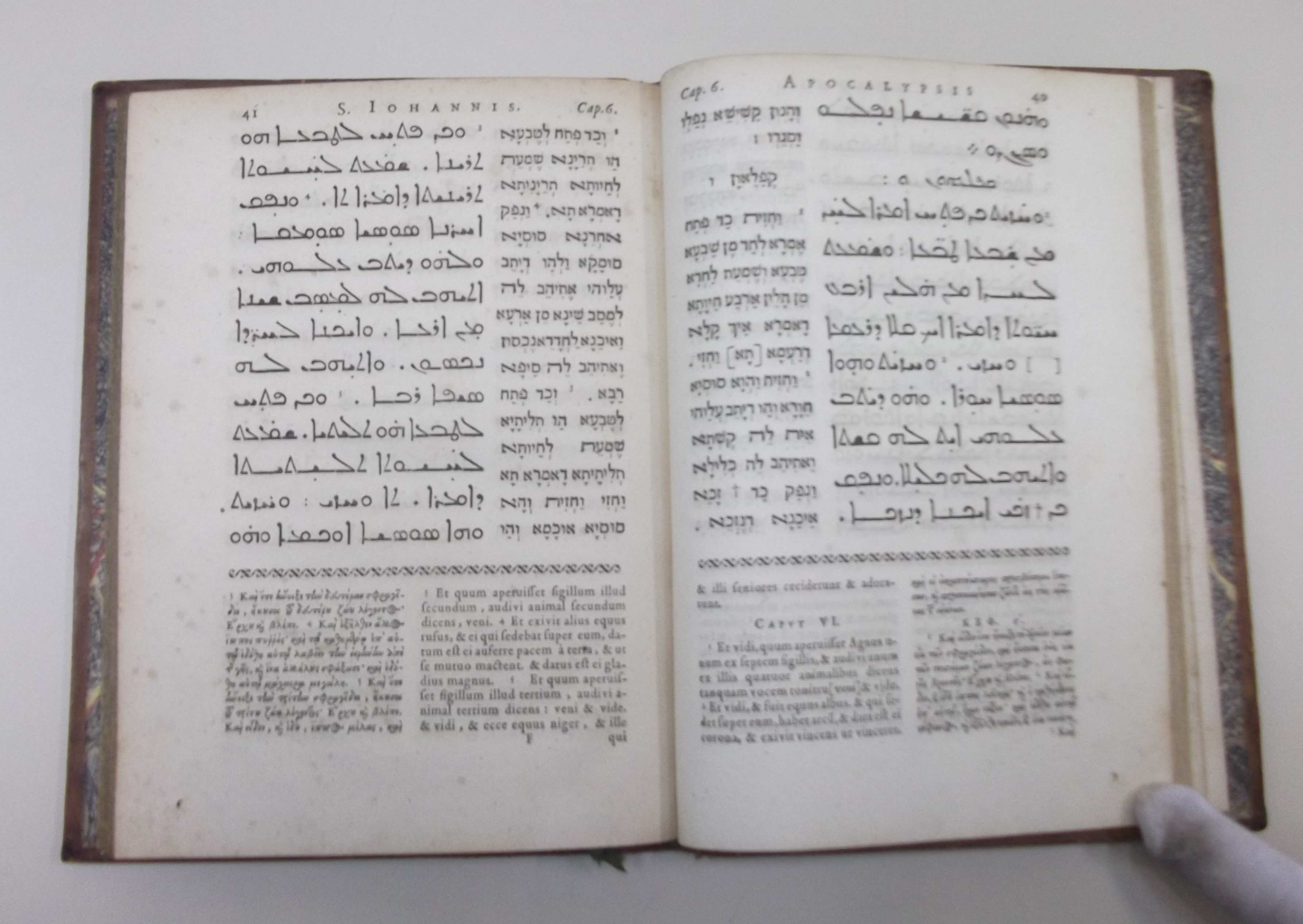

- …there are thousands more New Testament Greek manuscripts than any other ancient writing. The internal consistency of the New Testament documents is about 99.5% textually pure. That is an amazing accuracy. In addition there are over 19,000 in copies in the Syriac, Latin, Coptic, and Aramaic languages. The total supporting New Testament manuscript base is over 24,000.

The apologists John Ankerberg and John Weldon claim :

- For the New Testament we have 5,300 Greek manuscripts and manuscript portions, 10,000 Latin Vulgates, 9,300 other versions…

Finally, a low-level Christian polemicist excitedly proclaims (copying pretty much from Joseph Smith’s propaganda tract):

- We have today in our possession 5,300 known Greek manuscripts of the New Testament, another 10,000 Latin Vulgates, and 9,300 other early versions (MSS), giving us more than 24,000 manuscript copies of portions of the New Testament in existence today !

According to the above-referred polemicists and apologists, there are some 10,000 Latin Vulgates and 9,300 other “early” versions of the New Testament in existence. Presumably, this means that the “original” text of the New Testament can be reconstructed on the basis of these “early” versions. But how “early” are these versions ? How do they assist scholars in the textual criticism of the New Testament ? Can we really recover the “original text“

Evangelical scholar John J. Brogan draws our attention to some of these questions : “Furthermore, textual critics have recently been examining the question as to what we mean by recovering the “original text” or whether there is even such a thing as a single autograph and whether it is recoverable. Building on the evidence produced by source and redaction critics, textual critics affirm that many New Testament writings were redacted and expanded at later times. In some cases, it is extremely difficult and problematic to define what exactly an autograph is. For example, according to most textual critics, the autograph of Mark did not contain the longer ending (Mk 16:9 – 20), and the autograph of John did not contain the story if the woman caught in adultery (Jn 7:53 – 8:11). With a doctrine of the “inerrancy of the autographs,” what should we do with such passages ? Are these passages not inspired and therefore errant because they were not part of the autograph ? In attempting to identify the inspired, inerrant word of God, do we excise these passages, or can a case be made for the inspiration and authority of the longer, canonical form of the text?” (John J. Brogan, “Can I Have Your Autograph ? Uses and Abuses of Textual Criticism in Formulating an Evangelical Doctrine of Scripture”, in Vincent Bacote, Laura C. Miguelez, Dennis L. Okholm (eds.), Evangelicals & Scripture : Tradition, Authority and Hermeneutics, 2004, InterVarsity Press, pp. 103 – 104)

All of these issues are studied in detail in the following essay : E. Jay Epp, The Multivalence Of The Term “Original Text” In New Testament Textual Criticism on the basis of these versions ?

The purpose of this paper is to investigate these questions.

[toc]

Overview Of The Problems And Limitations With The Use Of Versions

“Versions” are simply the translations of the New Testament into other languages. The New Testament writers originally wrote their books and epistles in the Greek language whereas the versions are translations of their writings into other languages. Naturally, non-Greek speaking Christians wanted the text of the New Testament in their own local languages and so the New Testament began to be translated into other languages sometime in the mid to late second century. An important point to remember is that no matter how many thousands of translations exist, it remains that they are in a language that is different from the original language (Greek) of the New Testament writings. Thus, their use and value will always be limited. A number of issues need to be considered when dealing with versions/translations. The translator(s) may have had an imperfect command of the Greek and non-Greek languages. Moreover, certain features of the Greek syntax and vocabulary cannot be reproduced and conveyed in translations. This means that the translations need to be used with great caution and care. They may certainly assist scholars at times in ascertaining the general character of the underlying Greek and non-Greek manuscripts, but they cannot be used to reconstruct the “original” text of the Greek New Testament.

Kümmel in his introduction to the New Testament says :

But even the older translations are only to be used with caution as a witness for the Greek text : No translation exactly corresponds to the original even if it is literal. Nuances and special features of the Greek language (imperfect, aorist, perfect ; subjunctive, optative ; middle voice ; the multitude of prepositions, etc.) cannot be reproduced exactly in a translation. Often a translation variant is only the consequence of an interpretation of a difficult Greek text. Added to that, the textual history of the versions themselves is studded with problems.

W. G. Kümmel, Introduction To The New Testament, 17th Revised edition, 1975, SCM Press Ltd, p. 526

Metzger and Ehrman in their latest introduction to New Testament textual criticism add :

… certain features of Greek syntax and vocabulary cannot be conveyed in a translation. For example, Latin has no definite article ; Syriac cannot distinguish between the Greek aorist and perfect tenses ; Coptic lacks the passive voice and must use a circumlocution.

Bruce M. Metzger, Bart D. Ehrman, The Text Of The New Testament : Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, 2005, Fourth Edition, Oxford University Press, p. 95

Furthermore, as Kümmel pointed out above, the textual history of the various New Testament versions is also quite problematic. The versions were composed at different times and locations with the use of different Greek and non-Greek manuscripts — of varying quality — by scribes with a varying degree of command of the languages and these translations were subsequently copied/recopied by scribes of varying competence on the basis of different Greek and non-Greek manuscripts — also of different quality. Thus, from an early time there existed differing copies of the various translations. Certain versions were corrected against one another by multiple translators who made use of different Greek and non-Greek manuscripts for their purposes. With the absence of the originals and relying solely upon later copies of translations — all of unequal quality — scholars have to first apply textual criticism upon the versions in order to restore their early forms before they can be used for the textual criticism of the Greek New Testament. Quite understandably, this process tends to be even more complicated than the textual criticism of the Greek New Testament itself. According to Prof. Bruce Metzger and Prof. Bart Ehrman :

The study of the early versions of the New Testament is complicated by the circumstance that various persons made various translations from various Greek manuscripts. Furthermore, copies of a translation in a certain language were sometimes corrected one against the other or against Greek manuscripts other than the ones from which the translation was originally made. Thus, the reconstruction of a critical edition of an ancient version is often more complicated than the editing of the original Greek text itself.

Bruce M. Metzger, Bart D. Ehrman, The Text Of The New Testament : Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, 2005, Fourth Edition, Oxford University Press, p. 95

In light of these and other problems, Koester notes :

Translations, however, are notoriously difficult evidence, because they provide only a relative certainty with respect to the text of their Greek original.

Helmut Koester, An Introduction To The New Testament : History And Literature Of Early Christianity, 1982, Vol. 2, Walter De Gruyter, p. 19

Another problem with some of these versions, as we shall shortly see, is that they were produced on the basis of other versions and not the Greek manuscripts. Hence some of the versions are merely translations of translations and, therefore, barely used by textual scholars for the reconstruction of the New Testament text.

The difficulties of using the versions and their limitations are summarised by Christian scholars Lee Martin McDonald and Stanley Porter as follows :

Besides passing down the textual tradition in Greek, a number of churches early on engaged in the translation of the NT into their particular languages. For example, there are Syriac, Armenian, and Gothic versions, besides a wide range of Old Latin versions to consider, some of them in quite fragmentary form.46 Again, besides the problem that we do not possess the original of any of these versions and hence textual criticism must be done here as well, there is the serious question of translation. The complexity of the issue is that these texts are in languages different from the original text of the NT and require not only the understanding of these languages but knowledge of the various principles of translation that may have been used in the course of their development. There is the further problem, exacerbated by the difference in languages, of determining which text was before the translator. The problems with these translations necessarily introduce the question of whether they are good guides in establishing the original text of the NT. In some cases, however, they can help to clarify certain issues : for example, the Syriac Peshitta does not have John 21.…

Lee Martin McDonald and Stanley E. Porter, Early Christianity and Its Sacred Literature, 2000, Hendrickson Publishers, p. 584

Christian apologist David Stone writes :

…there are some 9,300 early manuscripts in other languages, notably Syriac, Coptic (Egyptian), Gothic, Armenian, Georgian, Ethiopic and Old Slavonic. Discovering the nature of the Greek text from which many of these were translated is not always easy. For a start, there may have been imperfections in the work of translation, especially if translators were not completely familiar with the languages they were dealing with. St. Augustine complains that ‘No sooner did anyone gain possession of a Greek manuscript, and imagine himself to have any facility in both languages (however slight that may be) that he made bold to translate it’ (On Christian Doctrine 2.11.16). In addition, there are certain features of Greek which simply cannot be translated directly into some other languages. It’s well known, for example, that, unlike Greek, Latin has no definite article, thus making the word ‘the’ impossible to translate.

David Stone, The New Testament (Teach Yourself Books), 1996, Hodder & Stoughton Ltd UK, p. 101

The most important translations of the New Testament are the Latin, Syriac and the Coptic translations.

So how are the versions useful when it comes to the textual criticism of the New Testament ? As noted above, they can, however, be useful at times to judge the general character of the underlying texts and to ascertain what particular words or phrases might have been in place within the base texts. The earliest versions — the ones undoubtedly based upon Greek texts — which we will discuss below, may act as a window — albeit indirect — to study the early transmission (and interpretation) of the New Testament text in different localities. Moreover, agreements between versions and the citations of the Fathers from different regions may reflect an earlier text. Primarily, however, the early versions act as useful evidence in New Testament textual criticism when they add or lack certain elements or passages.

In the words of the Alands :

5. The primary authority for a critical textual decision lies with the Greek manuscript tradition, with the versions and Fathers serving no more than a supplementary and corroborative function, particularly in passages where their underlying Greek text cannot be reconstructed with absolute certainty.

Kurt Aland, Barbara Aland, The Text of the New Testament : An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism, 1989, Second Edition, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company Grand Rapids, Michigan, p. 280

A Brief Survey Of The Primary Versions : Manuscripts, Significance, And Limitations

We will briefly go through the popular versions one by one and note the dates of their earliest witnesses and the overall importance of some of these versions.

Latin Vulgate and Old Latin versions

A large number of Christians spoke Latin, the language of much of the western part of the Roman Empire, and so the New Testament writings were translated into Latin for these Christians. Most scholars believe that the Gospels were first rendered into Latin during the last quarter of the second century in North Africa.

Problems emerged very soon, however, with the Latin translations of scripture, because there were so many of them and these translations differed broadly from one another.

Bart D. Ehrman, Misquoting Jesus : The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why, 2005, HarperSanFrancisco, p. 74

In his De Doctrina Christiana, Augustine complained that anyone obtaining a Greek manuscript of the New Testament would translate it into Latin no matter how little he knew the languages. Similarly, Jerome — a well-known scholar of the fourth-fifth century — also complained about the variety of Latin manuscript texts during his time, noting : “There are almost as many different translations as there are manuscripts.” The problem became so severe that near the end of the fourth century, Pope Damasus had to commission Jerome to produce an “official” translation of the New Testament in Latin so that it would be accepted by all the Latin-speaking Christians. Jerome went about with the task by selecting, what he believed was, a relatively good Latin translation as the basis and comparing its text with some Greek manuscripts at his disposal. This way, Jerome produced a new edition of the Gospels in Latin. Jerome’s Latin translation came to be known as the Vulgate (= Common) Bible of Latin-speaking Christians.

Unfortunately, Jerome’s revision was itself soon corrupted by the scribes during the course of its transmission, both through carelessness and by deliberate conflation with copies of the Old Latin versions.

It was inevitable that, in the transmission of the text of Jerome’s revision, scribes would corrupt his original work, sometimes by careless transcription and sometimes by deliberate conflation with copies of the Old Latin versions. In order to purify Jerome’s text, a number of recensions or editions were produced during the Middle Ages ; notable among these were the successive efforts of Alcuin, Theodulf, Lanfranc, and Stephen Harding. Unfortunately, however, each of these attempts to restore Jerome’s original version resulted eventually in still further textual corruption through a mixture of the several types of Vulgate text that had come to be associated with various European centers of scholarship. As a result, the more than 8.000 Vulgate manuscripts that are extant today exhibit the greatest amount of cross-contamination of textual types.

Bruce M. Metzger, Bart D. Ehrman, The Text Of The New Testament : Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, 2005, Fourth Edition, Oxford University Press, p. 106

Koester adds :

Today there are more than eight thousand known manuscripts of the Vulgate which demonstrate that the lack of uniformity existing at the time of Jerome was by no means overcome by his edition.

Helmut Koester, An Introduction To The New Testament : History And Literature Of Early Christianity, 1982, Vol. 2, Walter De Gruyter, p. 34

Jacobus H. Petzer concurs :

Although the Vg [Vulgate] was meant to bring an end to the diversity, the textual diversity obviously did not magically stop with the production of the Vg. Decay continued, with the new version creating even more mixture.46

Jacobus H. Petzer, “The Latin Versions Of The New Testament”, in Bart D. Ehrman & Michael W. Holmes (Editors), The Text of the New Testament In Contemporary Research : Essays On The Status Quaestionis, 1995, William B. Eedermans Publishing Company, pp. 123 – 124

Likewise, Bruce Metzger writes :

It was inevitable that, in the course of transmission by recopying, scribal carelessness corrupted Jerome’s original work. In order to purify the text several medieval recensions were produced…

Bruce M. Metzger, “The Early Versions Of The New Testament”, in Matthew Black (General Editor), Peake’s Commentary on the Bible, 2001, Routledge Co. Ltd., p. 671

Furthermore, most of the thousands of manuscripts of the Vulgate date from the medieval times, with the manuscript deemed “best” by most scholars — Codex Amiatinus — dating from the seventh or eighth century.

- …the oldest surviving complete Bible in Latin.…

[Kurt Aland, Barbara Aland, The Text of the New Testament : An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism, 1989, Second Edition, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company Grand Rapids, Michigan, p. 192]

The oldest manuscript of the Vulgate is Codex Sangallensis, written probably in Italy toward the close of the fifth century (ibid., p. 108).

Moving on, the Old Latin versions do not contain the entire New Testament

No codex of the entire Old Latin Bible is extant. The Gospels are represented by about 32 mutilated manuscripts, besides a number of fragments. About a dozen manuscripts of Acts are extant. There are four manuscripts and several fragments of the Pauline Epistles but only one complete manuscript and several fragments of the Apocalypse. These witnesses date from the fourth to the thirteenth century…

Bruce M. Metzger, Bart D. Ehrman, The Text Of The New Testament : Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, 2005, Fourth Edition, Oxford University Press, p. 101

In his classic survey of the New Testament versions, Metzger describes the state of the Old Latin manuscripts as follows :

…the manuscripts of the Old Latin versions are relatively few in a number and unpretentious in format.

No one manuscript contains the entire New Testament in the Old Latin version. Most of the copies are fragmentary and/or palimpsest.5

Bruce M. Metzger, The Early Versions Of The New Testament : Their Origin, Transmission, and Limitations, 1977, Clarendon Press, Oxford, p. 293

It was, after all, the notable differences and the lack of uniformity among these versions that prompted Pope Damascus to entrust Jerome with a new revision of the Latin Bible. Jacobus H. Petzer gives us an idea of the wide-ranging differences in the surviving Old Latin (and Vulgate) manuscripts :

The MSS [manuscripts], representing what is called the direct tradition, are not only often fragmentary but also often very late. This makes it difficult to decide where and how particular MSS relate to others. What makes the matter worse is that almost every MS [manuscript] is of a mixed nature. Most probably not one single “pure” Latin MS of the first millennium has survived. Every Vg [Vulgate] MS of the period contains OL [Old Latin] readings in a greater or lesser extent, and every OL MS seems to have been contaminated to some extent by Vg readings. Even in the MSS with a predominantly OL text, apparently few contain a text that represents one of the OL text-types “purely.” They are all mixed. This mixture takes on nearly every form possible. Some MSS contain block mixture, whereby the textual quality of the MS changes in specific parts, witnessing to different text-types in different parts. In some instances, the mixture takes the form of individual readings of a specific text-type incorporated into a MS that has a predominantly different text-type. In other instances, one finds a combination of these two kinds of mixture. Not only does the extant evidence, therefore, reflect only part of what once was, but it also does not represent any part of the mainstream of the history.

Jacobus H. Petzer, “The Latin Versions Of The New Testament”, in Bart D. Ehrman & Michael W. Holmes (Editors), The Text of the New Testament In Contemporary Research : Essays On The Status Quaestionis, 1995, William B. Eedermans Publishing Company, p. 119

Furthermore :

It seems that there was a kind of free handling of the Latin version early in its history, with new readings being created by almost everybody who worked with the text.

Jacobus H. Petzer, “The Latin Versions Of The New Testament”, in Bart D. Ehrman & Michael W. Holmes (Editors), The Text of the New Testament In Contemporary Research : Essays On The Status Quaestionis, 1995, William B. Eedermans Publishing Company, pp. 119 – 120

Therefore, scholars do not use the Vulgate or the Old Latin versions for the reconstruction of the earliest form of the New Testament text, let alone the so-called “original text.”

…the Latin version does not have any direct bearing on the “original” text (autographs) of the NT. It is much too late for that. Its only value as a direct witness, therefore, is to the history of the Greek text, insofar as it had contact with that history.

Jacobus H. Petzer, “The Latin Versions Of The New Testament”, in Bart D. Ehrman & Michael W. Holmes (Editors), The Text of the New Testament In Contemporary Research : Essays On The Status Quaestionis, 1995, William B. Eedermans Publishing Company, p. 124

Furthermore, Metzger adds :

In general the type of NT text which is preserved in Old Latin witnesses belongs to the so-called ‘Western’ family…

Bruce M. Metzger, “The Early Versions Of The New Testament,” in Matthew Black (General Editor), Peake’s Commentary on the Bible, 2001, Routledge Co. Ltd., p. 671

The importance of the Vulgate lies mainly to the degree to which it preserves the Old Latin portions or readings.

Some of the limitations of translating Greek into Latin are as follows : The aorist and perfect tenses cannot be differentiated ; lack of definite article ; verbs lack the perfect active participle and the present passive participle ; deponents lack the passive system and verbs lack the middle ; certain Greek synonyms are not precisely differentiated in Latin.

Coptic version

Palaeographically dating manuscripts of the Coptic versions is a tricky and complex business since there are almost no early dated Coptic documents. Thus caution is needed when assigning dates to Coptic biblical fragments.

The Sahidic (south or upper Egyptian) version (sa or sah) probably came into being bit by bit in the third century and preserves in fragments almost the whole of the NT. The oldest manuscript comes from the fourth century …

The age of the Bohairic (bo or boh) (northern or lower Egyptian) version is debated. But since we now know two manuscripts from the fourth/fifth century, the origin of this version before the end of the fourth century is certain.

W. G. Kümmel, Introduction To The New Testament, 17th Revised edition, 1975, SCM Press Ltd, pp. 536 – 537

However, most of the Bohairic witnesses are relatively recent — ninth-sixteenth centuries

There is also a papyrus codex in the Fayyumic dialect containing John 6:11 – 15:11, which is believed to date from the early part of the fourth century.

Frederik Wisse writes :

It is only for the late fourth and fifth century that Coptic MS attestation becomes substantial and representative of most of the NT writings. Even for this relatively late period, the witnesses represent a wide array of Coptic dialects and independent traditions. This suggests that the early history of the transmission of the Coptic text of the NT long remained fluid and haphazard.

Frederik Wisse, “The Coptic Versions of the New Testament,” in Bart D. Ehrman & Michael W. Holmes (Editors), The Text of the New Testament In Contemporary Research : Essays On The Status Quaestionis, 1995, William B. Eedermans Publishing Company, p. 133

As noted above, the early transmission of the Coptic text was fluid and haphazard. The Sahidic texts are widely divergent and were translated by different independent translators at various times. Although the Sahidic version generally agrees with the Alexandrian text form, it also contains many Western readings.

It [the Bohairic version] survives in many manuscripts, almost all of them of a very late date (the earliest complete Gospel codex still extant was copied A. D. 1174). [Bruce M. Metzger, Bart D. Ehrman, The Text Of The New Testament : Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, 2005, Fourth Edition, Oxford University Press, p. 112]

According to Plumley, while the Coptic (Sahidic) version may well be used in attempts to recover the original Greek New Testament text, its application in this regard would also be limited for a variety of reasons. Thus, there are many instances where the evidence of the Sahidic dialect would be unhelpful, limited, and ambiguous. A number of limitations associated with the Sahidic dialect are pointed out by Plumley, which include factors such as no case endings in Sahidic dialect ; inability to distinguish between d and t ; inability to truly represent the Greek passive ; Sahidic uses definite and indefinite articles differently ; inability to distinguish between the various Greek prepositions.

Be that as it may, the Coptic versions, in general, are primarily helpful when it comes to understanding the way how the New Testament text developed in Egypt. In the case of the Sahidic dialect, these can be particularly helpful to scholars involved in textual criticism, as well as to scholars in general because certain passages in the Sahidic preserve very ancient traditions of interpretation, which will be of interest to scholars investigating the history and development of Christian doctrine.

Syriac version

Under the rubric of “Syriac version” falls the Old Syriac version, the Diatessaron, the Peshitta (also known as the common version or the Syriac Vulgate), the Philoxenian, the Harclean, and the Palestinian Syriac versions.

Old Syriac version : This term is used to refer to the earliest Syriac translations of the New Testament.

Diatesseron : This was a gospel harmony produced by Tatian, either in Greek or in Syriac,

No complete copy of the Diatessaron exists. There is, however, a small fragment (0212) in Greek containing a portion of the Diatessaron which is placed around the mid-third century.

William Petersen, a leading expert and authority on the Diatessaron, writes :

No direct copy of Tatian’s Diatessaron exists. Instead, the scholar must be content with a wide array of sources and attempt to reconstruct the Diatessaron’s text from them. These sources, called “witnesses” to the Diatessaron, range in genre from poems to commentaries, in language from Middle Dutch to Middle Persian, in extent from fragments to codices, in date from 3d to 19th century, on provenance from England to China. Mastering these sources is the key to Diatessaronic scholarship.

William L. Petersen, “Tatian’s Diatessaron”, in Helmut Koester, Ancient Christian Gospels : Their History and Development, 1990, Trinity Press International, p. 408

Since the original text of the Diatessaron is lost, a major challenge for scholars is to reconstruct its text as much and as best as possible. The reconstruction of the Diatessaron text would enable scholars to get a “snapshot” of the Gospels as Tatian knew them around the mid-second century.

Peshitta : The Peshitta (abbreviated Syrp) has over 350 extant manuscripts, the earliest being from the fifth and sixth centuries.

Metzger and Ehrman write :

The textual complexion of the Peshitta version has not yet been satisfactorily investigated, but apparently, it represents the work of several hands in various sections. In the Gospels, it is closer to the Byzantine type of text than in Acts, where it presents many striking agreements with the Western text.

Bruce M. Metzger, Bart D. Ehrman, The Text Of The New Testament : Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, 2005, Fourth Edition, Oxford University Press, p. 98

David Parker writes :

It [the Peshitta] developed, by a gradual process of revision, out of far more ancient Syriac versions.

David Parker, “The New Testament,” in John Rogerson (Editor), The Oxford Illustrated History of the Bible, 2001, Oxford University Press, p. 117

Also :

The Peshitta New Testament seems to have come into existence more gradually, through revision of earlier Syriac translations.

Everett Ferguson, Michael McHugh, Frederick W. Norris (Editors), Encyclopedia of Early Christianity (Garland Reference Library of the Humanities, Vol. 1839) — One Volume, Second Edition, 1998, Garland Science, p. 901

The importance of the Peshitta lies mainly in the fact that it helps shed light on the character of the underlying Syriac translations and it may also be useful to understand the development of the textual tradition behind the Textus Receptus of the Greek New Testament.

The Philoxenian and/or Harclean Version(s): The unraveling of the Philoxenian (abbreviated Syrph) and/or the Harclean (abbreviated Syrh) version(s) constitutes one of the most confusing and complicated tangles in textual criticism.

Finally, the complex Syriac textual tradition continued to develop through an early-6th-century version made for Bishop Philoxenus by his chorepiscopus Polycarp in 507⁄8, which was either reissued by Thomas of Harkel in 616 with marginal notes or was revised by Thomas, again with marginal notes. On the former view, there is only one version involved (the Philoxenian); on the latter view, there are two separate versions, the Philoxenian (syph) and the Harclean (syh). Present evidence indicates that the latter view is correct and that Thomas of Harkel rather considerably revised the Philoxenian version — primarily to bring it into slavishly close conformity with Greek idiom — and also added marginal readings and a critical apparatus that marked off certain readings with obeli and asterisks. This apparatus and the marginalia are by no means fully understood, but at least some of the readings highlighted in these ways represent Greek variants known to Thomas. Whether any Philoxenian mss survive is uncertain ; the only ones plausibly defended as Philoxenian contain the Catholic Epistles and the Apocalypse, but these books were not part of the Syriac NT canon and therefore were never quoted by Philoxenus. The only certain remnants of the Philoxenian version would appear to be NT quotations in Philoxenus’ Commentary on the Prologue of John, recently published.

Eldon J. Epp, “Textual Criticism : New Testament,” Anchor Bible Dictionary (electronic edition ; Logos ; (c) 1997)

According to the Alands, in the year 616 Thomas of Harkel, monk and sometime bishop of Mabbug, undertook a revision of the Philoxenian version on the basis of collations he made of Greek manuscripts (three for the Gospels, two for the Pauline epistles, and one for Acts and the Catholic epistles), at the Enaton monastery near Alexandria.

But unfortunately the result only demonstrates that the Harklean text, except for the Catholic letters, is an almost (though not absolutely) pure Koine type.

Kurt Aland, Barbara Aland, The Text of the New Testament : An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism, 1989, Second Edition, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company Grand Rapids, Michigan, p. 199

The Harclean version is not used for the reconstruction of the “original” text of the Greek New Testament or even its early forms. Its importance lies primarily in the study of the Western text-type — the Harclean version is second only to Codex Bezae for the study of the variant readings of the Western text type for the book of Acts.

The Palestinian Syriac versions Syrpal : “Palestinian Syriac” refers to the Aramaic dialect ; this translation is known primarily from a lectionary of the Gospels, which is preserved in three manuscripts dating from the eleventh and twelfth centuries and there also exist fragments of the Gospels in continuous text, scraps of Acts and of several Pauline epistles.

About its significance, Helmut Koester writes :

Although this dialect is more closely related to the language of Jesus than the “Syriac” translations, this version from V CE has only minor text-critical significance.

Helmut Koester, An Introduction To The New Testament : History And Literature Of Early Christianity, (Vol. 2), 1982, Walter De Gruyter, p. 33

The versions we have discussed thus far — Latin, Syriac and Coptic — are the most important versions for text-critical purposes. The versions we will briefly discuss below are of secondary importance to scholars, mainly because their translation base is either disputed, or it is known that Greek manuscripts contributed only partially or influenced the translations at a later stage in a revision of their text.

Ethiopic versions

Scholars differ when it comes to the date of origin of the Ethiopic version ; some argue for a fourth-century date, others argue for the sixth century and still, others opine for a seventh-century date. Similarly, there is disagreement over the question of whether the translators translated from Greek or Syriac.

Moreover, the manuscripts of the Ethiopic version are extremely late, with the earliest known manuscript, a codex of the four Gospels, dating from the thirteenth century.

…none of the extant manuscripts of the version is older than perhaps the tenth century and most of them date from the fifteenth and later centuries.108

Bruce M. Metzger, Bart D. Ehrman, The Text Of The New Testament : Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, 2005, Fourth Edition, Oxford University Press, pp. 119 – 120

Rochus Zuurmond says :

A version is a version and not a Greek MS. Like other versions, Eth should be used with much caution in reconstructing the underlying Greek. In addition, a gap of about half a millennium separates the actual translation(s) from the earliest MSS. No one knows what happened to the text during that period. From the twelfth century onward there is ever-increasing confusion, caused by the influence of Arabic texts.

For the Gospels we have a few MSS of the thirteenth century or earlier. In the rest of the NT the earliest MSS come from the fourteenth century.

Rochus Zuurmond, “The Ethiopic Version of the New Testament”, in Bart D Ehrman & Michael W. Holmes (Editors), The Text of the New Testament In Contemporary Research : Essays On The Status Quaestionis, 1995, William B. Eedermans Publishing Company, p. 154

Analysis of the earlier form of the Ethiopic version reveals a mixed type of text, one that is predominantly Byzantine, although there are also occasional agreements with certain early Greek witnesses such as p46 and Codex Vaticanus (particularly in the epistles of Paul).

Regarding the value of the Ethiopic versions :

Generally, however, they have proved to be disappointing, for most copies are very much more recent than their appearance suggests : virtually no Ethiopian book is older than the fourteenth century and most, indeed, are only eighteenth-or even nineteenth-century. If the text is early, which it may be, it was evidently so revised and contaminated in the late Middle Ages that its evidential value for the Bible text is slight.

Christopher DE Hamel, The Book. A History of The Bible, 2001, Phaidon Press Limited, New York, p. 308

Therefore the Ethiopic versions are hardly used by textual scholars for the reconstruction of the Greek text of the New Testament. Their importance lies in the study of the development of the New Testament text at a much later date.

Armenian and Georgian versions

The Armenian Bible is often called the “Queen of the versions” due to its “quality, its idiomatic ease and graceful authority.“

The Arm 1 NT [the initial translation of the Bible] was translated from an Old Syriac base text during A.D. 406 – 414. Following the Council of Ephesus in A.D. 431, Greek copies of the Bible were brought from Constantinople and the Arm 2 [later revision — the Armenian majority text] revision was based on the Greek text. (Joseph M. Alexanian, “The Armenian Version Of The New Testament,” in Bart D. Ehrman & Michael W. Holmes (eds.), The Text of the New Testament In Contemporary Research : Essays On The Status Quaestionis, 1995, William B. Eedermans Publishing Company, p. 157)

See also the discussion in Bruce M. Metzger, The Early Versions Of The New Testament : Their Origin, Transmission, and Limitations, 1977, Clarendon Press, Oxford, pp. 164 – 165 ; Phillip Comfort, Encountering the Manuscripts : An Introduction to New Testament Paleography & Textual Criticism, 2005, Broadman & Holman Publishers, pp. 93 – 94. According to Phillip Comfort :

The first translations of the New Testament into Armenian were probably based on Old Syriac versions. Later translations, which have the reputation for being quite accurate, were based on Greek manuscripts of the Byzantine text type but also show affinity with Caesarean manuscripts.

Phillip Comfort, Encountering the Manuscripts : An Introduction to New Testament Paleography & Textural Criticism, 2005, Broadman & Holman Publishers, p. 94

Some noteworthy features of the Armenian version should also be mentioned. The Old Testament included apocryphal books such as the History of Joseph and Asenath, the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs, whereas the New Testament included the Epistle of the Corinthians to Paul as well as a Third Epistle of Paul to the Corinthians — which was read at Mass by Christians as late as the thirteenth century. Moreover, of the 220 Armenian manuscripts examined by Colwell, only 88 included the longer ending of Mark (Mark 16:9 – 20) — 99 end at verse 8 without comment and in others there are indications that the scribes had doubts regarding the authenticity of the passage. The shorter ending (i.e., “But they reported briefly to Peter…”), however, occurs in a number of Armenian texts. In any case, it is most unlikely that the last twelve verses of Mark (the longer ending) were a part of the original Armenian version.

In his excursus on the limitations of the Armenian in representing the Greek New Testament text, Rhodes says that while at times even the fine nuances of the Greek are reflected in astonishing detail in the Armenian due to its flexibility and sensitivity, yet “there are also instances where it is utterly useless for distinguishing between different Greek readings.“

Coming to the Georgian version, probably in the fourth century the Bible was translated into Georgian from Armenian (Arm. 1) and this Georgian version is also deemed an important witness to the Caesarean type of text.

Besides the above, there are other New Testament versions as well, but they are of even little use to scholars for textual criticism :

Other ancient translations have only little significance for textual criticism, or their use is burdened with too many difficulties. These include the Anglo-Saxon, the Nubian, and the Sogdian translations, as well as the translations into Persian and Arabic. Except for a small portion of the Arabic version, they were all made from other translations and not from Greek originals.

Helmut Koester, An Introduction To The New Testament : History And Literature Of Early Christianity, (Vol. 2), 1982, Walter De Gruyter, p. 35

The versions which are deemed useful are the ones which were made either directly from a Greek text or were subsequently thoroughly revised from a Greek base.

The Contribution Of Versions In The Making Of Novum Testamentum Graece 26th and 27th Editions

To summarise the discussion very briefly : the Latin, Syriac and the Coptic versions of the New Testament are the most important versions to textual scholars. After these come the Armenian, Ethiopic and the Georgian versions. Here we would like to know what role these versions play towards the preparation of a critical text of the New Testament. Let us take the widely used 27th edition of the Novum Testamentum Graece (also known as Nestle-Aland27) as an example.

We will begin with the second batch of versions first. Regarding the contribution made by the Armenian, Georgian, Ethiopic etc., versions towards the preparation of the Novum Testamentum Graece 27th edition, we are told :

The Armenian, Georgian, Gothic, Ethiopic and Old Church Slavonic versions are rarely cited in the present edition, and then only if they are of special significance for a particular reading (cf. Mk 16,8) … While it is true that several important studies of the Armenian, Georgian, Ethiopic and Old Church Slavonic versions have appeared in recent decades, research in these textual traditions has by no means yet achieved conclusive results. In particular, the origins and development of these versions and their relationship to the Greek textual tradition remains so controversial that no thoroughgoing use of their evidence is possible.

Barbara Aland, Kurt Aland, Johannes Karavidopoulos, Carlo M. Martini, Bruce M. Metzger (eds.), Novum Testamentum Graece, 27th Edition, 1993, Stuttgart : Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, pp. 70 – 71

Moving on to the first batch of versions (Latin, Coptic, and Syriac), the editors acknowledge that the principal emphasis is placed upon the Latin, Syriac and Coptic versions because they were “unquestionably” based directly on the Greek at an early time. Moreover, we are informed that they happen to be the most fully studied versions and because their “value as witnesses to the textual tradition of the Greek New Testament…has become increasingly clear through decades of debate.” However, they proceeded to add :

The versions are cited only where their underlying Greek text can be determined with confidence. They are generally cited only where their readings are also attested by some other Greek or independent versional evidence. Only in rare instances do they appear as the sole support for a Greek reading…

Barbara Aland, Kurt Aland, Johannes Karavidopoulos, Carlo M. Martini, Bruce M. Metzger (eds.), Novum Testamentum Graece, 27th Edition, 1993, Stuttgart : Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, pp. 63 – 64

Moreover, we are cautioned that :

Differences in linguistic structure between Greek and the languages of the versions must be carefully noted. Variant readings reflecting idiomatic or stylistic differences are ignored. One the whole, versions can only reveal with more or less precision the particular details of their Greek base.5 In instances where the witness of a version is doubtful, it is not noted.6

The versions still enjoy an important role in critical decisions because they represent Greek witnesses of an early period. But their value for scholarship today in comparison with earlier generations has been modified by the great number of Greek manuscripts on papyrus and parchment discovered in the twentieth century.

Barbara Aland, Kurt Aland, Johannes Karavidopoulos, Carlo M. Martini, Bruce M. Metzger (eds.), Novum Testamentum Graece, 27th Edition, 1993, Stuttgart : Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, p. 64

Thus, to list the main points :

• Rather than revealing the original text of the New Testament, versions may only reveal with a degree of precision and approximation the text of their underlying manuscript.

• Versions are cited only when their underlying Greek text can be determined with confidence.

• Versions rarely appear as sole witnesses ; they are cited only when there is support in a Greek or an independent version.

• Versions such as the Armenian, Georgian, Gothic, Ethiopic, Slavonic etc., rarely appear in Nestle-Aland27.

It is also worth noting the role played by the versions in the preparation of the 26th edition of the Novum Testamentum Graece. The Alands write :

It must be emphasized that the value of the early versions for establishing the original Greek text and for the history of the text has frequently been misconceived, i.e., they have been considerably overrated. An inadequate appreciation of how their linguistic structures differ from Greek has all too often permitted the early versions to be cited in critical apparatuses of Greek texts where their evidence is irrelevant. Nestle-Aland26 advisedly restricts citation of the versions in its apparatus to instances where their witness to a Greek exemplar is unequivocal.

Kurt Aland, Barbara Aland, The Text of the New Testament : An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism, 1989, Second Edition, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company Grand Rapids, Michigan, p. 186

At this juncture, we must remind ourselves that the Greek manuscripts are the primary witnesses for the restoration of the New Testament text. The versions and the patristic citations are secondary lines of evidence, playing no more than a supportive and corroborative role as indirect witnesses to the New Testament text. To quote the Alands again :

5. The primary authority for a critical textual decision lies with the Greek manuscript tradition, with the versions and Fathers serving no more than a supplementary and corroborative function, particularly in passages where their underlying Greek text cannot be reconstructed with absolute certainty.

Kurt Aland, Barbara Aland, The Text of the New Testament : An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism, 1989, Second Edition, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company Grand Rapids, Michigan, p. 280

Finally, it should be noted that Novum Testamentum Graece is a working text. It should not be looked upon and confused as representing the “original” text of the New Testament. This is how the editors of Novum Testamentum Graece describe the 27th edition :

It should naturally be understood that this text is a working text (in the sense of the century-long Nestle tradition): it is not to be considered as definitive, but as a stimulus to further efforts toward defining and verifying the text of the New Testament.

Barbara Aland, Kurt Aland, Johannes Karavidopoulos, Carlo M. Martini, Bruce M. Metzger (Editors), Novum Testamentum Graece, 27th Edition, 1993, Stuttgart : Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, p. 45

The purpose of the 27th edition of the Novum Testamentum Graece is to present the user with a working text “with the means of verifying it or alternatively of correcting it.“

This text was agreed by a committee. When they disagreed on the best reading to print, they voted. Evidently, they agreed either by a majority or unanimously that their text was the best available. But it does not follow that they believed their text to be ‘original’. On the whole, the textual critics have always been reluctant to claim so much. Other users of the Greek New Testament accord them too much honour in treating the text as definitive.

D. C. Parker, The Living Text Of The Gospels, 1997, Cambridge University Press, p. 3

The same cautionary remarks are made by Moises Silva regarding the United Bible Societies’ Greek New Testament :

…we can hardly afford to encourage the view that the work of New Testament textual criticism is for all practical purposes complete. If anything, papyrological discoveries and the research of the last several decades have made us more aware of the complexities of the textual history of the Greek New Testament. Nonetheless, the term may be used simply to indicate that the text in question has received widespread acceptance. In my opinion, this acceptance is well deserved, but one need not concur with this judgement to recognize the facts of the case. The UBS text reflects a broad consensus and it thus provides and convenient starting point for further work. Far from considering this text as definitive, therefore, we ought to do all we can to improve it.

Moises Silva, “Modern Critical Editions And Apparatuses Of The Greek New Testament,” in Bart D. Ehrman & Michael W. Holmes (eds.), The Text of the New Testament In Contemporary Research : Essays On The Status Quaestionis, 1995, William B. Eedermans Publishing Company, p. 290

Hence none of the extant witnesses of the New Testament, be it the Greek manuscripts, the versions, and the patristic citations, give us access to the “original” text of the New Testament.

Conclusions

To assert that there are “24,000 manuscript copies of portions” of the New Testament or that the New Testament manuscript base is “over 24,000” is to give a misleading impression. It is misleading because such blanket assertions leave readers with the impression as if all manuscripts are of equal value and status. They conveniently ignore the fact that hardly a fraction of this base is deemed important by textual critics for the reconstruction of the New Testament text. The same misleading impression is conveyed when mention is made of the 10,000 LatinVulgates and the 9,300 “other early” versions as if the Greek New Testament text can be painlessly reconstructed in its entirety on their basis. The problems and limitations associated with the Latin Vulgates, the “other early” versions and, in fact, with versions in general, are quietly omitted as if they do not exist. The magical figure of “24,000” is thus arrived upon by overlooking the many problems through simplistically adding and piling up every tiniest bit of fragment, late medieval manuscripts, late versions and lectionaries (late non-continuous texts).

It should be clear by now that there can be no wholesale reproduction of the Greek New Testament text on the basis of the above-discussed versions. The different New Testament versions are of unequal value, importance, and use for text-critical purposes. Some are more/less important/useful than others. For example, some versions shed light and give insights on the transmission of the Greek text at an early period and location for which there are no extant Greek manuscripts ; some may shed light on the transmission and development of specific documents and text types (i.e., book of Revelation, the Western text type); some versions play little or no role in the understanding of the Greek text ; some versions are important when it comes to understanding the development of the Greek text at a later stage, though of little and/or no use when it comes to knowing about the early transmission of the Greek text. In short, the versions act as indirect witnesses of unequal quality and value to the different stages of the transmission and development of the Greek and non-Greek New Testament text, informing us, at most, about the nature of their underlying manuscript(s) rather than the very text of the Greek autographs.

Phillip Comfort says that the Old Latin, Coptic and the Syriac versions are used for “establishing the original text” of the New Testament. However, immediately thereafter he weakens his own assertion when he adds the following caveat :

However, readers should be aware that ancient translators, as well as modern, took liberties in the interest of style when they rendered the Greek text. In other words, there is no such thing as a literal, word-for-word rendering in any translation. Therefore, the witness of the various ancient versions is significant only when it pertains to significant verbal omissions and/or additions, as well as significant semantic differences. One should not look to the testimony of any ancient version for conclusive evidence concerning word transpositions, verb changes, articles, or other normal stylistic variations involving noun insertions, conjunction additions, and slight changes in prepositions. The citation of such versions for these kinds of variant readings in the apparatuses of critical editions of the Greek New Testament can be quite misleading.

Phillip Comfort, Encountering the Manuscripts : An Introduction to New Testament Paleography & Textual Criticism, 2005, Broadman & Holman Publishers, p. 91

In other words, the idiosyncrasies associated with the different versions cannot allow the complete extraction of the underlying Greek text, let alone the “original” text of the New Testament. Their use and value will always be limited. Moreover, we have already seen that the Nestle-Aland27 is described by its editors as a working text ; it should not be mistaken and confused as the “original” New Testament text.

Clearly, the text of the Greek New Testament would be of a much more precarious and uncertain nature if we were dependent solely upon the witness of the ancient versions. The Greek manuscripts remain the first and the primary evidence for the text of the New Testament, without which the New Testament text would be even more uncertain if reliance was placed solely upon the ancient versions and the patristic citations combined. The latter two sources act only in a secondary, collaborative and supportive capacity.

This is not to say that the witness of the versions is entirely worthless. According to Wisse, the importance of the Coptic, Latin and Syriac versions lies in the fact that they are “indirect witnesses” to an early state of the Greek New Testament text that is otherwise poorly attested by Greek witnesses and also because these versions “localize the form of the Greek text that they translated.“

…the fact is that we can only approximate the date of this fragment’s production within fifty years at best (it could as easily have been transcribed in 160 as 110). Moreover, we do not know exactly where the fragment was discovered, let alone where it was written, or how it came to be discarded, or when it was. As a result, all extravagant claims notwithstanding, the papyrus in itself reveals nothing definite about the early history of Christianity in Egypt. One can only conclude that scholars have construed it as evidence because, in lieu of other evidence, they have chosen to. (Bart D. Ehrman, “The Text as Window : New Testament Manuscripts and the Social History of Early Christianity,” in The Text of the New Testament In Contemporary Research : Essays On The Status Quaestionis, Bart D Ehrman & Michael W. Holmes (eds.), 1995, William B. Eedermans Publishing Company, p. 372)

Thus, we lack Greek manuscripts completely from the first century and for the major part of the second century. To make matters worse, the earliest Greek witnesses also happen to be quite fragmentary. Therefore, there is a rather poor attestation of the Greek New Testament in the earliest period.

A number of factors need to be taken into account when dealing with the witness of the versions. Often we are faced with significant gaps between the date of origin of the versions and the dates of their earliest manuscript. Moreover, these versions present their own unique textual problems to scholars — over the centuries, many were corrected, revised and adapted at various stages by different scribes, of varying capacities, using different Greek and non-Greek manuscripts in the process. As a result, scholars have to first apply textual criticism upon the versions in order to restore their early forms before they can be used for any purpose. This process tends to be far more difficult and complicated than the textual criticism of the Greek New Testament itself. But most importantly, even if their early forms are restored, the fact remains that we are still left with nothing more than translations of particular Greek manuscripts. No translation is perfect. Translators always make a variety of mistakes and, more frequently, all of the nuances, features, feel, and the subtle characteristics of a language cannot be perfectly reproduced into another language. There is no method of “capturing” a language with exactness into another language. Every language brings with it unique set of problems which cannot be overcome by translators. The fact that these are translations, different from the original language, makes their use limited right from the outset.

And Allah knows best !

[cite]

Bibliography

Leon Vaganay, Christian-Bernard Amphoux (trans. Jenny Heimerdinger), An introduction to the textual criticism of the New Testament, 1991, 2nd Revised & Updated Edition, Cambridge University Press.

Phillip Comfort, Encountering the Manuscripts : An Introduction to New Testament Paleography & Textual Criticism, 2005, Broadman & Holman Publishers.

Helmut Koester, Introduction to the New Testament Volume 2 : History and Literature of Early Christianity, 1982, Walter De Gruyter.

Helmut Koester, Ancient Christian Gospels : Their History and Development, 1990, Trinity Press International.

Kurt Aland, Barbara Aland, The Text of the New Testament : An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism, 1989, Second Edition, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Eldon J. Epp, “Textual Criticism : New Testament,” Anchor Bible Dictionary (electronic edition ; Logos ; (c) 1997).

E. Jay Epp, The Multivalence Of The Term “Original Text” In New Testament Textual Criticism

Bart D. Ehrman & Michael W. Holmes (Editors), The Text of the New Testament In Contemporary Research : Essays On The Status Quaestionis, 1995, William B. Eedermans Publishing Company.

Bruce M. Metzger, Bart D. Ehrman, The Text Of The New Testament : Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, 2005, Fourth Edition, Oxford University Press.

Bart D. Ehrman, Misquoting Jesus : The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why, 2005, HarperSanFrancisco.

Raymond E. Brown, S.S, An Introduction To The New Testament, 1997, The Anchor Bible Reference Library, Doubleday.

Christopher DE Hamel, The Book. A History of The Bible, 2001, Phaidon Press Limited, New York.

Lee Martin McDonald and Stanley E. Porter, Early Christianity and Its Sacred Literature, 2000, Hendrickson Publishers.

Everett Ferguson, Michael McHugh, Frederick W. Norris (Editors), Encyclopedia of Early Christianity (Garland Reference Library of the Humanities, Vol. 1839) — One Volume, Second Edition, 1998, Garland Science.

W. G. Kümmel, Introduction To The New Testament, 17th Revised edition, 1975, SCM Press Ltd.

David Stone, The New Testament (Teach Yourself Books), 1996, Hodder & Stoughton Ltd, UK.

Vincent Bacote, Laura C. Miguelez, Dennis L. Okholm (ed.), Evangelicals & Scripture : Tradition, Authority and Hermeneutics, 2004, InterVarsity Press.

Barbara Aland, Kurt Aland, Johannes Karavidopoulos, Carlo M. Martini, Bruce M. Metzger (eds.), Novum Testamentum Graece, 27th Edition, 1993, Stuttgart : Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft

Bruce M. Metzger, The Early Versions Of The New Testament : Their Origin, Transmission, and Limitations, 1977, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Hyeon Woo Shin, Textual Criticism And The Synoptic Problem In Historical Jesus Research : The Search For Valid Criteria, (Contributions To Biblical Exegesis & Theology, 36), 2004, Peeters-Leuven, Bondgenotenlaan.

Matthew Black (General Editor), Peake’s Commentary on the Bible, 2001, Routledge Co. Ltd.

D. C. Parker, The Living Text Of The Gospels, 1997, Cambridge University Press.

Last Updated on July 13, 2019 by Bismika Allahuma Team